Africa’s Latest Democratic Awakening: Implications for Western foreign policy – By Rudy Massamba

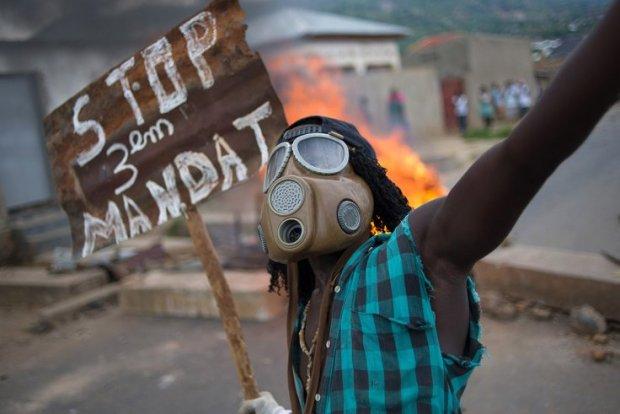

Protestors in Burundi against President Nkurunziza’s attempt to stand for an unconstitutional third term.

Sub-Saharan Africa in general, and Francophone Africa to be more precise, stand at a metaphorical crossroads. A great number of long-time African rulers, many of whom came to power through coups, are facing pressure like never before. The advent of new technologies, along with associated social media and other innovative methods of communication have breathed new life into pro-democracy citizen movements.

Though disgruntled citizens never really ceased to voice their frustrations, they can do it more often through cyber activism, which shields them, to a great extent, from government repression. As recent events in Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and Burundi have proved, citizens are now less afraid to take to the streets. This newfound bravery is not simply spontaneous. It can first be attributed to evolving political dynamics on the continent, especially since the Arab Spring. Second, it can be attributed to a change in relations between many African countries and their most engaged Western partners, the United States and France.

President Obama made his vision for Africa pretty clear when he stated during a 2009 visit to Ghana that “Africa doesn’t need strong men, it needs strong institutions.” The following year, he launched the Young African Leaders Initiative (YALI) to invest in the next generation of African leaders. President Obama’s second term has been particularly marked by an intensification of warnings against African rulers tempted to modify their country’s constitutions for their personal ambitions. Such warnings have been delivered, either in person or in writing, by Secretary of State John Kerry, Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Linda Thomas-Greenfield, and US Special Envoy for the DRC and the African Great Lakes Region, Russ Feingold.

French president Francois Hollande, on the other hand, publicly spoke about the need for African rulers to uphold their countries’ constitutions on several occasions, including the fifteenth Francophonie Summit, a major event that gathered the leaders of 57 French-speaking countries in Dakar, Senegal in late November 2014.

“Where constitutional rules are abused, where freedom is violated, where the alternation of power is prevented, I affirm here that the citizens of these countries will always find, in the Francophone sphere, the necessary support to uphold justice, law and democracy” said President Hollande, whose speech was very similar in message to the one Francois Mitterrand, France’s longest-serving president, made in 1990 at the sixteenth Franco-African Summit. President Mitterrand’s speech, delivered in the coastal resort of La Baule, France, set the tone for fresh relations between France and its former colonies, by conditioning aid on the adoption of democratic reforms.

Many French colonies had become authoritarian single-party regimes shortly after independence. While the La Baule speech has been credited with helping to restore multi-party politics in the region, Francophone Africa’s democratic experiment, with the exception of a handful of countries, has essentially been a failure. Fraudulent elections have enabled many rulers to hold on to power indefinitely. In the worst cases, they helped establish unpopular political dynasties in Gabon, Togo, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

It is important for African rulers to not only learn from history, but also to read the signs of the time. The end of the Cold War permitted the United States to abandon some of its African allies, the most prominent of which was arguably Zairian dictator Mobutu Seke Seko. As illustrated by the La Baule speech, it also prompted France to revise its foreign policy towards Africa. In the same fashion, the Arab Spring certainly encouraged, to some extent, both countries to reevaluate their Africa policy.

Just weeks before the fifteenth Francophonie Summit, President Hollande wrote a letter to Burkinabé President Blaise Compaoré in which he urged the longtime leader to renounce revising his country’s constitution to extend his term, a process that eventually led to his downfall through a popular uprising in late October 2014. “What happened in Burkina Faso should serve as a lesson to all those who want to stay in power by violating constitutional order,” said President Hollande during the summit.

In the face of relentless citizen aspiration for greater political and civil liberties, despotic African rulers are desperate to maintain good relations with their Western partners, who on the other hand, may now exploit dwindling oil prices to compel the former to become more democratic. This is especially true for oil-dependent economies like Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, and the Republic of the Congo.

Regardless of how the West decides to persuade African rulers to change their ways, a new wave of democracy is making its way throughout the continent. This is the same wave that swept away a stubborn Blaise Compaoré. The same wave that recently pushed large groups of youth to the streets of Kinshasa to protest a controversial electoral bill. And finally, the same wave that gave the people of Burundi the courage to publicly denounce their president’s decision to run for a third term.

Africans are ready, more than ever, for true democracy. One that leaves no place for un-needed constitutional revisions.

Rudy Massamba is Assistant Programme Officer for Central Africa at the National Endowment for Democracy.

My Civic Social Epistemological Consideration regarding Leadership in African States with a view to the future as mandated in forthcoming Elections in Africa 2015 and 2016.

Political public social civic life in African states, which have generally come under indigenous rule the mid to late decades of the twentieth century, to a high degree contains the imprimatur of earlier forms of civic social organization. When the African colonies were accorded independent statehood unfortunately following intense severe political public animated violence and presented with a constitution based on either the Western Westminster model or European Parliamentary construct, deeper indigenous civic social cultural traits often triumphed formal institutions. Similarity to Western Democratic Parliamentary Rule of Law Process became increasingly difficult to discern. Therefore, African leaders have elected to operate through highly personalized transactional patron-client networks that are usually, but not always based on ethnic and regional groupings. Within these indigenous ethnic social civil networks there are generally ‘Big Men’ who wield disproportionate influence in the exercise of power and tend always to circumvent the formal rules entailed in a robust pluralist system of democratic governance by and for the people. An ongoing persistent problem of African states has been the unfortunate fact that civil boundaries which are a legacy of colonial conquest unfortunately and forcibly brought together indigenous peoples of different ethnic identities and religion who had most little in common. The most challenging salient task of political leadership was to create, to generate and to inspire a sense of national identity. Good institutions are important, but a great deal does depend on the quality and integrity of leadership. If leaders themselves circumvent the institutions for personal private gain and thus undermine their civic civil social political legitimacy including breach of public civic civil social trust, then sound institutional structures may not be enough to contain this breach of civic civil social trust.

Leadership does matter, but it is visionary and inclusive leadership which the poorest, least able and most divided societies need most urgent, not a ‘Strongman’ or a ‘Big man’. Many of the most economic impoverished countries of the world are among the most ethnically diverse. This compounds the problem of making civic civil social public electoral competition work prescriptively, for there is an atavistic strong tendency for voting [to the extent that the election is reasonably fair free open] to be strictly along the liniments in the promotion of ethnic loyalty. The temptation is to assume that what is needed by this kind of ethnically diverse society in which most of ‘the bottom billion’ of the world’s poor live is a ‘Strongman’. Paul Collier in his book “War Guns and Votes: Democracy in Dangerous Places” advances this counterfactual. Documenting the damage civic internal state sanctioned violence does to the prospects for economic growth, in addition to its devastating immediate effects on people’s lives, Paul Collier concludes that ‘bad as democracy is’ in ethnically diverse failing states inhabited by the world’s poorest people, ‘dictators are even worse’!

Thanks for this very interesting piece. The caption on the picture refers to Nkurunziza’s ‘unconstitutional’ third term. I see the relevance of the Burundi situ to the piece, of course, but I’m genuinely not sure whether it’s fair to count Nkurunziza’s first term, which didn’t follow an election. The same arguments weren’t applied, for example, to the DRC and I think it’s unlikely they’ll be applied to Buhari if he seeks a second term in Nigeria. You’ll be more au fait with the detail that I – do you have a take on that stuff?

Great stuff. I like the real democracy with regards to social media.

Cheers!

As usual Africa divided in francophone and anglophone, leaving us, Ethiopia in the vaccum. What do you guys make of this week’s ethiopian election drama and the strategic ambivalence and western policies double standard?

Love to hear

Lemma

American involvement in fostering democracy?!….hmmmm….last time they tried in Iraq and Afghanistan and Libya and Somalia and ….various South American countries later….it didn’t turn out well did it…. As for ‘investing’ in the young African leaders of tomorrow, I call that more of the same, thank you. Nothing new here, look behind every African dictator and you will see the hand of the west…. And the few exceptions are always dislodged in the interests of “democracy”

The French on the other hand, have dropped all pretences, they are in Mali, firmly lodged in Niger and resurgent in CAR(no, the French never left) this writer must be the most optimistic person I’ve ever read….me, I don’t get fooled.