The “People’s Victory”: President-elect Kaboré and the democratic road ahead for Burkina Faso

It’s tempting to think Roch Kaboré will simply replicate Compaoré’s old system, but the reality is that something has fundamentally changed in Burkina Faso.

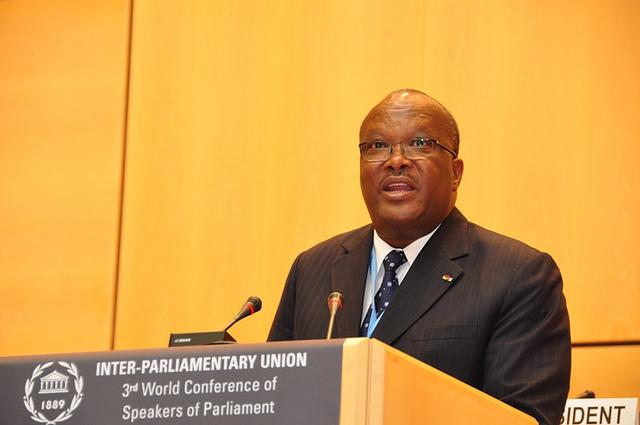

President-elect Roch Marc Christian Kaboré is Burkina Faso’s first civilian president in half a century. Photograph by Third World Conference.

When Roch Marc Christian Kaboré is sworn in as the new president of Burkina Faso, he will be the country’s first elected civilian head of state in 50 years. Not all the country’s military leaders have been cut from the same cloth, but the withdrawal of the military from politics will be a welcome change.

We have seen this trend in action already when the army stood with the people in opposing General Gilbert Diendéré’s coup in September 2015, which led to the subsequent disbanding of the Presidential Guard (RSP) and the arrest of its leaders. However the successful election of 29 November represents the beginning of a new democratic era.

For Pascal Sankara, brother of Burkina Faso’s revolutionary former president Thomas Sankara, the election represents a turning point in terms of the role of the military in politics. But he explains that many other changes are also necessary. “The authority of the state and its institutions must be re-established, and that means the army must go back to doing their job of simply protecting national territory,” he told African Arguments. “National reconciliation and justice must be immediately addressed, and justice that is applied equally to all Burkinabé. We must end the tradition of leaders using political power for personal interests. Kaboré has been elected, but not his entire family.”

With municipal elections not being held until next year, the recent presidential and legislative elections in this immediate post-insurrection context heavily favoured those with financial means. In fact, many activists and legislative candidates, particularly those lacking funds, bemoaned the fact that they had not had time to build grassroots networks and momentum at the local level. As such, we might view the new government as something of a transitional regime, at least until other political actors are able to develop their bases in conditions of greater fairness. Indeed, multiparty elections and a freely elected president do not ensure democracy. They merely open the door.

A unique election

Kaboré takes the reins of a country that is eager to move forward and get back to work. This partly explains Kaboré’s success at the polls despite his 26 years of collaboration with strongman president Blaise Compaoré who was overthrown in a popular uprising in October 2014. But while Kaboré has a strong mandate, his effectiveness will still depend on his success in building coalitions and finding compromise within the National Assembly.

The legislative elections – in which an astonishing 99 different political parties took part – were much more hotly contested. Kaboré’s party, the People’s Movement for Progress (MPP), took 55 of the 127 seats. Lacking the necessary majority, it will most likely find common cause with Zéphirin Diabré’s Union for Progress and Reform (UPC), which took 33 seats. Compaoré’s former party, the Congress for Democracy and Progress (CDP), landed a surprising 18 seats, but any MPP-CDP coalition seems unthinkable at this point. The Sankarist party, Union for Rebirth/Sankarist Party (UNIR/PS), which was dealing with internal divisions and a lack of funding, took a modest five seats.

After a tumultuous year in Burkina Faso, the election unfolded peacefully and calmly. According to election observers and participants, the election was well organised, owing largely to the work of CENI (National Independent Electoral Commission) and organisations such as CODEL (Convention of Civil Society Organizations for the Domestic Observation of Elections). The Balai Citoyen civil society group also mobilised the youth and played a key role in getting out the vote, helping achieve an impressive 60% voter turnout in a very rural country with poor road networks. International observers lauded the election for its peacefulness and transparency and even characterised it as a “model.”

One of the reasons for the peaceful nature of the elections, and the lack of post-election contestation or challenge, is that the outcome was never really in question. But it was also the case that simply voting freely was enough for many voters, regardless of the results. Having had Compaoré imposed on them for years, they were happy to vote in an election in which Compaoré was not on the list of candidates.

According to Paul Sankara, another brother of the former president Thomas Sankara, the result was rarely in doubt. “It’s not a surprise to anyone that Kaboré has won given the strength of his political machine,” he says. “He has long been considered the most capable of challenging Blaise Compaoré. Even before [journalist] Norbert Zongo’s murder in 1998, Zongo wrote an article in which he hypothesised that Roch could form a party and challenge Compaoré.

“But this was a unique election because there was no incumbent, not even a candidate from the incumbent party. At this point we are just happy that it is anybody but Blaise. Kaboré will be the next president, but for now this is the people’s victory.”

The road ahead

Kaboré’s political machine has been decades in the making, and it overlaps considerably with Compaoré’s system. He comes from an illustrious Catholic family belonging to the Mossi majority. The son of Charles Bila Kaboré, a former minister under former president Maurice Yaméogo and banker, “Rocco,” as many call Roch Marc, followed in his father’s footsteps, eventually entering finance and taking up the banking trade.

He studied in France for years and joined the student left, becoming an important member of the Union of Communist Struggles – Reconstructed (ULC-R). Within the revolutionary government of Thomas Sankara, Kaboré served as the head of Burkina Faso’s main bank. Thus he has participated in the more “direct democracy” of the Sankara years, but has also moved among the financial elites.

After Sankara’s assassination in 1987, Kaboré rallied to support Compaoré and quickly emerged as his right-hand man. This served him well. He ascended through the political system, occupying various ministerial posts en route to becoming Prime Minister and the president of Compaoré’s party, the CDP. But in response to Compaoré’s efforts to alter presidential term limits, Kaboré defected from Compaoré’s party in January 2014 and formed a new opposition party, MPP, which included such pillars of the Compaoré regime as Salif Diallo and Simon Compaoré.

Kaboré joined the opposition just in time to catch the wave of political activism and popular mobilisation leading to Compaoré’s overthrow. He then out-financed and out-manoeuvred his main rival, Zéphirin Diabré, en route to the presidency.

As a political operator, Kaboré has prevailed through his ability to find consensus and compromise, and having allies across the political spectrum. He will need to put all these political skills to good use in balancing the restiveness of the labour unions, youth, and leftist parties on the one hand, and the political competition with the UPC and CDP as well as the entrenched business interests on the other. He will have to draw on his finance expertise in trying to pull the country out of its economic doldrums.

Kaboré has a long to-do list awaiting him, but he also brings with him an excellent team and decades of experience. It remains to be seen how far he will go in undoing the Compaoré system, characterised as it has been by corruption, embezzlement, nepotism, vote buying, human rights abuses and mismanagement.

However, there are already signs that aspects of this system are withering away under popular pressures and government action. Thus, while it is tempting to speculate that the MPP will simply replace the CDP and return to business as usual, things have changed in Burkina Faso. The recent uprisings have given the people the confidence to challenge injustice and voice their discontent.

Kaboré comes to power in these unique circumstances, and at least in his official declarations he seems aware of the task ahead of him: “We must get to work immediately…. so that the sacrifice of all these martyrs are not in vain,” he said in his acceptance speech. “We must work together to heal the wounds and to succeed in truth and justice, national reconciliation and consolidating social cohesion among all Burkinabé.”

After nearly three decades under Compaoré and a tumultuous year since his overthrow, the people of Burkina Faso will be hoping their new president is true to his word.

Brian J. Peterson is Associate Professor of History, Union College, New York. A specialist on francophone West African history, he has written a book on Islam in Mali, entitled Islamization from Below: The Making of Muslim Communities in Rural French Sudan, 1880-1960 (Yale University Press, 2011). He is currently completing a book on the life, political thought, and legacy of Thomas Sankara.