Courting controversies: Ghana’s Electoral Commission under fire ahead of close elections

Four years after disputed elections, things are again not going smoothly for Ghana’s electoral body.

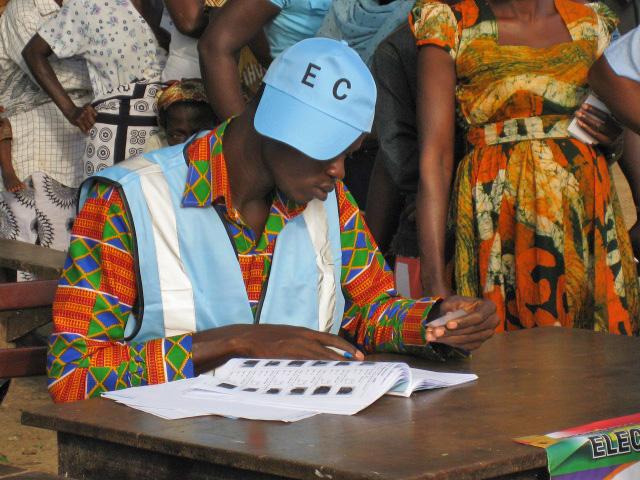

In 2012, there were several irregularities in the election process. Credit: Peter Lewenstein/BBC.

With the political temperature in Ghana rising ahead of its finely balanced 7 December elections, the Electoral Commission (EC) is coming under intense scrutiny. The body has been a cause of running complaints since the reintroduction of multi-party politics in 1992. This transition followed nearly 20 years of military rule by Jerry Rawlings; the EC oversaw Rawlings’ electoral victories in 1992 and 1996.

The Electoral Commissioner who oversaw the return to formally civilian government was Kwadwo Afari-Gyan, a political scientist appointed by Rawlings. Afari-Gyan remained in his position until 2015, having conducted six elections. The last of these, in December 2012, was hotly contested between Ghana’s two largest parties: the ruling National Democratic Congress (NDC) under President John Mahama, and the New Patriotic Party (NPP) led by Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo.

In these closely fought elections, Mahama – who had risen to Head of State less than five months previously, after President John Atta Mills’ death – was pronounced the outright winner. The EC declared that he had won 51% of the vote to Akufo-Addo’s 48% in the first round.

However, the NPP launched a Supreme Court challenge to the result that kept Ghana on tenterhooks for much of 2013. Live broadcasts of the proceedings allowed Ghanaians to pore over the mechanics of conducting national elections. And as lawyers ran through voodoo arithmetic and piles of incomplete results sheets, it became harder for some Ghanaians already inclined to see their public institutions as corrupt to accept the EC’s procedures as capable of delivering elections that reflect the will of the people.

Results declarations hadn’t been signed by more than one opposition party in some constituencies, signalling that their polling agents disagreed with the results or hadn’t been present. There were persistent murmurs about under-declaration of opposition tallies everywhere from the Greater Accra Region on the coast to the Upper East on the border with Burkina Faso. The figures in some results were transposed. Multiple voting seemed rife in some areas. Worse still, the chief witness for the defence, Afari-Gyan, often appeared uncertain how the election had been organised at ground level.

What were the basic procedures? What was the law on acceptable proof of results from a polling station? Did a declaration sheet have to be signed by representatives of all the parties standing in that area? If one party agent hadn’t signed the sheet for their polling station, did this invalidate the result? How many voters were there on the electoral roll? How do you define “over-voting”? Did every voter have to prove their identity using the biometric identification system introduced for the 2012 election? What sort of identification did you have to present in order to register to vote?

For days, the Supreme Court was surrounded by pro-NDC protesters, armed with bamboo canes and vowing to protect the declared result. They would not be disenfranchised, they said.

After eight months of evidence, with over 30,000 members of the security forces standing by, the Supreme Court passed a 5-4 verdict dismissing the challenge. The petitioners, including Akufo-Addo, accepted the decision and urged disappointed NPP supporters to do the same. However, the judges made it clear in their detailed judgments that reform was vital and that the next election could not be conducted the same way. The changes they set out included recommendations on redesigning results forms, retraining of EC staff, a review of the voters’ register, and consensus-building with all the political parties.

Vigour and rigour

In the wake of the judgment, the EC embarked on a charm offensive, repeatedly assuring Parliament that it was making changes to its way of working. And in June 2015, the government took a bold step: as Afari-Gyan retired, it named Charlotte Osei, the 46-year-old head of the National Commission for Civic Education, as his replacement. With her background in the law and relative youth, it was hoped she would inject vigour, rigour and fresh ideas into the EC.

Nevertheless, sensing stasis, pro-opposition groups under the banner of the Let My Vote Count Alliance (LMVCA), soon launched street protests to put pressure on the Commission to compile a fresh voters’ register. This, activists said, was the only way of ensuring a fair election in 2016. But when, on 16 September 2015, they marched on the EC’s headquarters in Accra, they met with riot police armed with tear gas, rubber bullets, water cannon, batons and bamboo canes rather like those brandished by the NDC supporters outside the Supreme Court in 2013. Police said the demonstrators had veered off the agreed route. Several protesters were beaten; one was hit in the face by a rubber bullet and lost an eye.

Osei quickly retreated to the bunker, refusing to meet LMVCA and even suspending cross-party talks. Everyone had a complaint, from the Convention People’s Party (heirs to the mantle of Kwame Nkrumah) to the breakaway Progressive People’s Party under Paa Kwesi Nduom and the comedic Ghana Freedom Party under Akua Donkor.

After insisting for months that the 2016 election would be held in November to allow adequate time before the year end for a possible presidential run-off, the EC was obliged to accept it would not be able to marshal resources in time. It reset the date for 7 December.

Blossoming legal challenges

The charm offensive had quickly gone adrift and the first newsworthy action by the Commission under Osei was to redesign its logo at an undisclosed cost, a move that provoked widespread derision. Meanwhile, various spats resumed, such as the one over signatures on declaration forms.

In May this year, for example, the Supreme Court found in favour of a civil suit brought by supporters of two opposition parties. One of the main points of contention revolved around whether a National Health Insurance Scheme card – which is not proof of nationality – was acceptable ID when registering to vote. The NDC backed the EC in arguing the cards should be valid, while the NPP disagreed. The Supreme Court, upholding its original recommendations, instructed the EC to remove NHIS cardholders’ names from the voters’ register. The EC came back with a list of names that looked distinctly underwhelming.

On 11 October, the Commission was at the centre of another dispute when it disqualified 13 of the 17 candidates hoping to run for president, including the former First Lady Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings. It cited reasons ranging from certain parties’ failure to provide evidence that they had a national structure, to individuals signing registration papers for more than one candidate.

The ensuing uproar unleashed a slew of cases in the civil courts, the Progressive People’s Party’s Nduom sounding the most determined to have the decision against him overturned. The Chief Justice pledged to resolve the disputes quickly so as not to create further delay, and their claims are being heard at the High Court. Konadu-Rawlings lost her first suit at this court on 27 October but, like Nduom, is threatening to go all the way to the Supreme Court. The NDC argues that the disqualified candidates should stop sulking and accuses NPP and LMVCA of fomenting violence against an EC that’s doing good work.

And the EC’s travails go on. In late October, yet another lawsuit was filed that may further prolong the wrangling over electoral paperwork. There were repeated stops and starts over when the voters’ register and final list of polling stations would be released to the political parties. The Commission kept changing its mind over whether it could afford to put the contract for electronic transmission of results out to tender; the NPP objected to the idea, arguing it would be unconstitutional and a waste of money, while the NDC and its allies accused NPP of deception and causing confusion.

And on 26 October, the paramount chief of the Asante was moved to chide the EC for allowing the “sham” political party phenomenon to spread whereby there has been a proliferation of political parties that critics believe are simply proxies for the NDC or NPP.

Though officially independent and free from state control, opposition activists see the EC as a political football, kicked about by the party in power. Its conflict resolution mechanisms appear not to work, hence the repeated recourse to the law courts. That the bulk of its budget comes from the government does not help. The Commission announced last year that it would need 1.3 billion cedis ($330 million) to mount the elections; Parliament agreed provision for just under 900 million cedis ($230 million), leaving Osei and her team to make up the shortfall.

Whether the EC will be able to assert its independence, gain public trust, get its house in order and conduct a smooth election on 7 December remains to be seen. The blossoming of legal challenges doesn’t augur well.

Nana Yaa Mensah works for the New Statesman.

Mrs Charlotte Osei will be speaking at the RAS event Democracy in the Digital Age: How Ghana is preparing to deliver the 2016 Elections at 7pm 2nd November in London.

The EC’s chairperson adamant posture and attitude is not and have not been promising ever since she assumed the position. The controversies and legal issues prior to this crucial election is very dangerous for the nation. She is not fit for the office. Really disappointed she couldn’t make it to the Wednesday event. What’s the essence and priority of changing the commission’s logo than that of a national coat of arm which has been used for years? Where is the patriotism that she’s supposed to exhibit as a Ghanaian citizen? She’s not fit for the office.

Charlotte is not fit for the role. I hope ghana replaces her soon. It can’t be a ‘ job for life’ for her. I am very happy with the SC verdict re the order to.allow all disqualified candidate to amend their errors, she could have done this easily with wasting the court’s time .

I strongly believe she feels the wind of change which is blowing across the country. Ghanaians are tired of poor systems and corruption. It’s about time the nation moves forward.

How come that the NPPNEVER GET THE OPPORTUNITY TO APPOINT A EC Chairman/ woman.

The EC has been rigging elections for the NDC since 1992 and the time for this nonsense to stop is long overdue. Ghanaians have realised that the EC has exploded the voters registers with hidden polling stations in the homes of NDC supporters where NDC members go over vote. Its very sad because this is a recipe for a civil war. The EC is corrupt and rigs for the NDC. God has seen them all. SHAME ON THEM ALL