How to put the ‘African’ back into African Studies

From 1993 to 2013, the proportion of articles written by Africa-based scholars plummeted in two leading journals. Why?

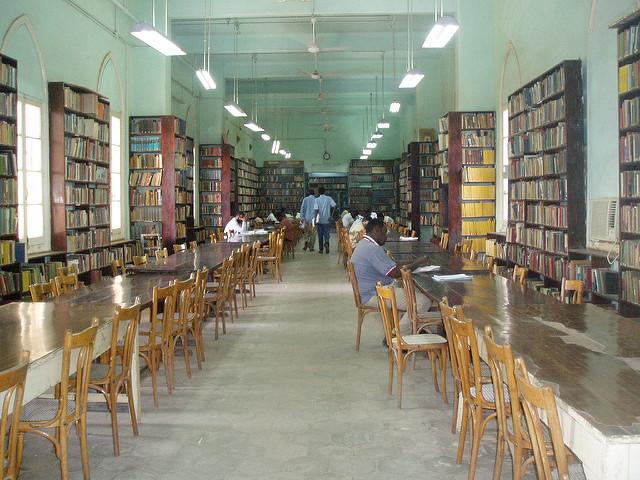

University of Khartoum Main Library. Credit: Book Aid International.

Earlier this year, a new piece of research looking at the make-up of contributors to two leading Africa-focused journals found that the proportion of articles written by authors based in Africa had plummeted. Ryan C. Briggs and Scott Weathers found that whereas in 1993, about 30% of articles in African Affairs and the Journal of Modern African Studies were written by Africa-based academics, by 2013, this figure had halved to just 15%.

This change was not because scholars on the continent were submitting fewer articles, the researchers found, but because of falling acceptance rates. The authors could not explain why this was the case through their analysis, but said that editors in informal conversations have suggested the quality of research is often a key barrier.

Much more examination is needed to add to their research, which covers just two journals over two decades. But if the trend of dramatically declining acceptance rates found is representative, some clues as to why this is the case may be found by looking at what daily life is like for academics at African universities.

[Where is the ‘African’ in African Studies?]

Under pressure

To begin with, scholars at African universities face several pressures. Some of these are more direct such as political pressures to avoid certain topics or opt for safe ‘neutral’ issues. But academics also face less visible strains – particularly in terms of time and resources – that can interfere significantly with research.

For instance, administrative duties eat up large amounts of many Africa-based academics’ time and energy. Meanwhile, faculty members, especially younger ones, have to deal with heavy teaching loads. Class sizes at African universities tend to be large – often reaching a few hundred at basic undergraduate courses – and are mostly taught by a single individual.

At the same time, economic pressures can weigh heavily. In many African countries, the typical income of a university lecturer is not sufficient to live a reasonable middle-class lifestyle, meaning other opportunities to generate extra income are needed.

One way to earn money from publishing in Kenya, for example, is to have a school textbook adopted for the local Primary or Secondary curriculum. This can divert academics from scholarly publishing, which earns no financial rewards.

There is also the temptation to ‘moonlight’ at neighbouring campuses to earn extra money teaching on a part-time basis. This has become particularly prevalent in Kenya because of the proliferation of satellite campuses across the country.

And finally, there is also the lure of paid consultancies. Such offers can be appealing and still involve research, but the research is set by the employer. This means that the outputs generated are likely to more policy-based and not easily convertible into the kind of scholarship typically suitable for Western academic journals.

[Decolonising Makerere: On Mamdani’s failed experiment]

Out of the loop

While scholars at African universities have been facing growing economic and time pressures over the past decades, the routes to being published in international journals may also have been getting less clear. Academics based in Africa generally face significantly higher barriers compared to their international counterparts on this front.

Although the Internet is increasingly accessible and university libraries are becoming better connected to international journals, for example, there is still a huge deficiency in terms of access to recent publications, in particular books. Additionally, even where electronic journals may be available in theory, slow internet connections mean scholars struggle to access articles or may find themselves paying for quicker connections at cyber cafes rather than at their universities.

The avenues to getting published have also become tougher. In earlier decades in East Africa, there were several locally-based journals – such as Uganda Journal, Kenyan Geographer, East African Geographical Review, Tanzania Notes and Records, and Transafrican Journal of History – that could provide a first step on the publication ladder. But many of these have since ceased operations.

Being published and being cited in international articles is also partly a question of one’s network, and more recent generations of African scholars may not have had the same opportunity to develop social and professional links in Europe and North America as earlier generations. Many of the first generation of Africa-based scholars completed their higher degrees abroad before returning to Africa to teach. But today’s academics are more likely to have done their higher degrees at African universities and may not have had the same interaction with those from outside the continent.

This can lead to a gradual weakening of their contact with “mainstream” scholarship in Europe and North America, and even with the English language as written and spoken in scholarly discourse. Even if the Internet now provides access to both language and scholarship, it cannot fully replace the influence of individual mentors and networks.

Possible solutions

The obstacles facing Africa-based scholars are multi-faceted and go beyond these daily realities. This means that reversing the trend of falling acceptance rates in journals will be difficult to address, but there are a few measures that could be taken.

Firstly, confronting funding shortages will be crucial. There is an urgent need for financial support for academic research that is not directed by NGOs or consultancies. Back in the 1970s, Kenyatta University had its own research funds that were administered through the Deans’ Committee, but today there is a greater need for researchers to draw on foreign funds. This not only requires time, but leads to problematic power dynamics.

Although it will not be straightforward to mobilise greater finances, reasonable national funds for research as well as higher basic salaries for university lecturers – so they are not required to spend their time supplementing their earnings rather than focusing on academia – would significantly help their ability to conduct research.

Another area of support would be to help Africa-based scholars build stronger international networks. For example, travel programmes that involved visits to North American or European universities – such as the six-month fellowships offered through the Cambridge University African Studies Institute in the early 2000s – would help African academics meet with other researchers, editors and access international libraries.

On a less extensive scale, shorter (two to three week) workshops in which African scholars could bring their work-in-progress for critique and advice from people experienced in publishing would significantly help the quality of research. This could be combined with Internet-based communication, but face-to-face contact and discussions with others can be highly beneficial.

Much will need to be done to increase the number of Africa-based scholars publishing in international journals, but these measures could provide an important start.

Celia Nyamweru (Professor Emerita, Ph.D. Cambridge) is a former Academic Dean at Kenyatta University, Kenya, where she worked for 19 years. She also taught at St. Lawrence University in Canton, NY for 19 years and is currently Adjunct Professor at Pwani University in Kilifi, Kenya. Her five books include Rifts and Volcanoes and a co-edited volume on African Sacred Groves. Her current work involves social and cultural issues at the Kenya Coast.

This piece was partly adapted from a Q&A on the OUP blog.

Unfortunately, this seems likely. Although we should realize that this is an effect of a deeper phenomenon that I call generically “lack of confidence and serenity.” Sociology creations and creativity speaks volumes about this. Usually we run a lot, survival, the ruinous rivalry and copycat! Our researchers part of our societies, and often do too !!! African issues are they not essentially food , safe, colonial, consumatariste, etc. issues? Gratitude to the author of article.

Another problem is that journals like JMAS and African Affairs are designed with the assumptions of western scholarship in mind. Articles require extensive library resources, and the assumptions of western academic structure.

One way to meet Africa on its own terms, would be to meet it on its own terms, is through literature, film, music, and so forth. Africans (not only westerners) excel at such forms of expression, but western academia does not necessarily reward it. What about giving journal space over to literary expression, in addition to the occasional literary criticism that now gets published?

On a related note, why not also send more westerners to Africa as part of their studies and career trajectories? Current policies of tenure and promotion reward the “stay-at-home academic.” Sure, Africans should come to western universities, but a few years teaching in an African institution will also make “Africanists” more sensitive to issues beyond the traditional publish or perish mode of the west.

These are vital questions, so it’s great to see them on the African Arguments blog. Thanks Cecilia. The need to rejuvenate African HE has climbed national and international policy and funding agendas in recent years. A lot has been done / is being done, by the donors of course, but also increasingly by African governments and agencies like the AfDB. Of course the ever-increasing size of the system (new universities being created every year, often without the academic base to support them) means the need is ever growing too.

I couldn’t agree more about the “agendas” issue. Substantial proportions of research funding rely on external donors in many countries – (apparently 47% in Kenya) although the creation of AESA (with donor funding, but managed locally) seems like a positive step-change (I’ve put some thoughts together about this here https://medium.com/@jonharle/who-drives-research-in-developing-countries-19e6d13b9b5f).

The specific points you raise on African publishing are important too. Worth mentioning a few efforts to address those

African Journals Online (www.ajol.info) based in South Africa provides a platform for African-published journals to enhance their visibility, manage the publication process, and work to improve the publishing quality. At INASP our AuthorAID (www.authoraid.info)

programme matches experienced academics across the world with early career scholars. It’s a fantastic way to help them to navigate the often mysterious process of academic publication, or to offer advice on methods and proposals. We’re always looking for new mentors – and that includes postdocs and PhDs with experience to share. It can often be win-win (see this recent piece http://www.authoraid.info/en/news/details/1126/).

We also run a series of online courses – and are seeing researchers grow in confidence, submitting articles for publication, and with greater success. While nothing can replace the interactions of meeting face to face, and while technology isn’t the panacea, offering online support does mean it’s possible to provide support at low cost and at scale.

Access to academic journals and books is certainly critical. Often the picture is significantly better than many assume – or experience. Huge volumes are available, but awareness is low (relationships between faculty and librarians are important, but are not always effective) or use is low (the consultancy jobs that you mention don’t typically create much demand for “scholarly” materials). The Kenya Library and Information Services Consortium (www.klisc.org) makes over 40,000 full-text journals and books available to its member universities and research institutes (having negotiated hard with publishers to lower costs). Doing this, and building the mechanisms to do it at a national level isn’t easy – but it is being done. http://www.inasp.info/publishers

Similarly, academic IT bodies, NRENS (national research and education networks) have made huge strides across the continent. The Research & Education Network of Uganda (www.renu.ac.ug) is connecting campuses to high speed fibre networks, training IT engineers at universities, and developing new research data services. Read more here http://www.inasp.info/en/publications/details/215/.

Undoubtedly a huge amount still needs to be done. And this must be led by African universities and the organisations that support research in a country, and it must be funded by African governments if agendas are to be locally defined. But there are also some real – and African-led – successes to celebrate too!

This is a neo-colonial question. African knowledge production should not be measured by number of publications in journals controlled by white people.

Many thanks to all who have commented – useful information and suggestions from Jon and Tony. and to Kwame Zulu Shabazz – you raise an interesting point – might it be said that even the very universities in which African scholars are working are in fact neo-colonial creations? And how should African knowledge production be measured? I am going to meet a number of younger colleagues at Kenyatta University in Nairobi on Monday December 19th and I hope to engage them in this debate.

Thank you Celia for raising the issue. Indeed a lot needs to be done to enhance writing in journal articles by African scholars – this can also be linked to research driven by Africans through national research funds. In addition, there is need need to also apply other ‘measures’ of African knowledge production, and not only by number of publications in western based journals.