Life and coal: The other way Africa can leapfrog on energy

Off-grid renewables are not the only, or the best, way for the power-starved continent to increase energy generation and reduce emissions.

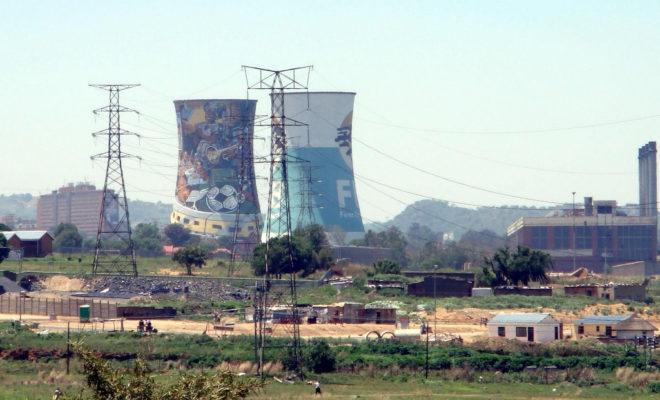

Orlando Power Station is a decommissioned coal fired power station in Soweto, South Africa. Credit: Jorge Láscar.

Ever since Africa’s mobile revolution eliminated the need for expensive fixed-line telecoms, the idea of the continent “leapfrogging” the rest of the world has become gospel.

Both inside and outside the continent, commentators have for years enthused about the possibility of Africa skipping the arduous steps taken by other regions of the world and launching straight into more advanced technologies.

This idea has been particularly strongly advocated in the area of energy. Rather than following the path of developing more traditional on-grid forms of power generation, many argue that Africa can jump straight to renewables and off-grid technologies.

Businesses such as the Swedish company TRINE have tried to make this a reality. Under its model, customers get use of solar kits to generate electricity, paying for the equipment in monthly instalments. Already, nearly 100,000 people across Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Senegal and Uganda are signed up.

Ventures such as this are tapping into a massive potential market. Sub-Saharan Africa is by far the least electrified continent, with an estimated 632 million people without basic energy – more than half the global total. Spain alone generates about as much electricity as the region’s 48 countries put together.

Add to this state of affairs the need to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions, and the appeal of Africa overtaking the rest of the world and going straight into renewable off-grid alternatives is obvious.

[Africa’s no-regret route to industrialisation]

But unfortunately, things aren’t so simple. Africa can and should leapfrog the rest of the world on energy, but not necessarily in the ways that are usually proposed.

Power for all?

The idea of rolling out off-grid solar technology in Africa has clear attractions. But it should be noted that Africa is not the only region trying to use localised solar panels to make up for an inadequate power grid. In India, Narendra Modi’s “Power For All” pledge has involved installing solar panels in thousands of villages.

This has brought greater electricity access to some, but residents of these newly “electrified” villages continue to suffer from a highly intermittent and uncertain supply. Particularly in the winter, people are plunged into darkness early in the evening as the energy runs out, forcing villagers to turn to highly polluting kerosene lamps. The technology as it stands is insufficient to provide the kind of consistent and reliable supply needed.

However, even if off-grid solar initiatives could provide a steadier source, the potential would still be highly limited. Such solutions may be able to power remote villages, benefiting several households. But in order for African countries to truly develop and industrialise, energy capacity will need to be increased on a huge scale.

Renewables can be part of that, but especially given governments’ limited financial resources, the region needs to expand power generation in the most reliable, efficient and cost-effective way possible. At the moment, that means large-scale production, including the use of fossil fuels. Renewable energy sources may be getting cheaper, but they are still economically unviable for many governments.

Sub-Saharan Africa must of course be part of tackling climate change. But especially given that the region has contributed the least to the problem yet faces many of the direst consequences of it, the burden should not lie with a power-starved Africa.

[Climate change adaptation is not just about vulnerable countries]

Old energy, new technologies

This reality is well-understood on the continent.

The African Development Bank’s “New Deal on Energy for Africa”, which aims to provide universal access to energy for all Africans by 2025, explicitly includes fossil fuels. In 2016, the then chair of the African Union Commission, Nkosozana Dlamini-Zuma, commented: “coal will be part of the energy mix. I don’t think it should be the sole source of energy but it will be part of the mix”.

And earlier this month, former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan argued that “the cost of transitioning to renewables may be prohibitively high in the short term – especially for countries that use their sizeable endowments of coal and other fossil fuels to generate energy”.

Indeed, coal currently accounts for around 24% of all electricity generated in Africa, and the continent will struggle to develop without tapping into its plentiful coal deposits. Although World Bank financing may have shifted away from fossil fuel projects, investors from China and elsewhere have jumped into the fray. Meanwhile, both the BRICS New Development Bank and the African Development Bank have made developing coal a priority for development.

Relying on fossil fuels may seem like a conservative and environmentally-damaging approach. But if done the right way, Africa can still leapfrog the rest of the world and curb global carbon emissions at the same time.

Once again, India offers some key lessons. There, ground-breaking carbon capture technologies have passed the proof-of-concept hurdle and are now offering systems that can be implemented in existing or new power plants to mitigate the impact of burning fossil fuels.

The Indian government also has plans to take up to 40GW of ageing coal plants offline and replace them with supercritical ones. According to Power Minister Piyush Goyal, this transition to new technologies will have an even greater impact on reducing emissions than the 100GW India is planning in renewables.

In fact, the latest iterations of coal power plants emit less than 100g of CO2 per kilowatt-hour of electricity generated. That’s almost as little as a traditional photovoltaic solar panel.

As India is experiencing, renewables can be costly and intermittent, and struggle to provide enough baseload power. It hopes that investing in supercritical coal power plants can bridge the gap and satisfy both climate commitments and energy security.

The debate over energy sources remains heated, but one universal point of agreement is that Africa’s chronic energy poverty needs to be solved as quickly as possible.

Leaving 632 million Africans without power not only means that 2-4% of GDP growth is squandered annually, but it means that 255 million people are forced to seek healthcare in facilities with no electricity. It means that four million people (primarily women and children) die each year because they are forced to burn wood and dung for heating and as cooking fuel.

Continent-wide electrification will save millions of lives. This cannot wait, and as Annan put it earlier this month: “African governments [must] harness every available energy option, in as cost-effective and technologically efficient manner as possible, so that no one is left behind”.