Kenyatta vs. Odinga: A study in contrasts

Ahead of Kenya’s elections, the opposition stalwart is promising to shake things up, while the incumbent vows to protect the status quo.

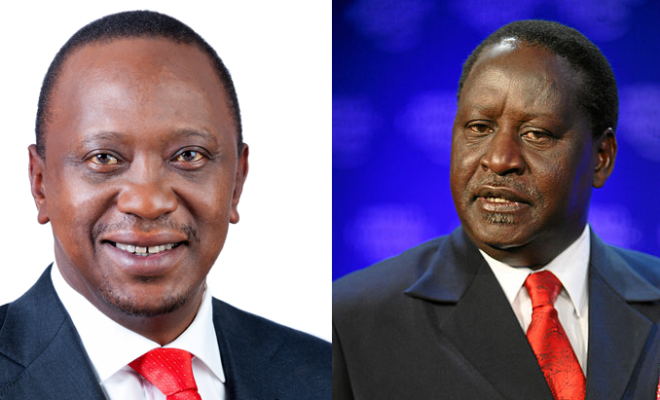

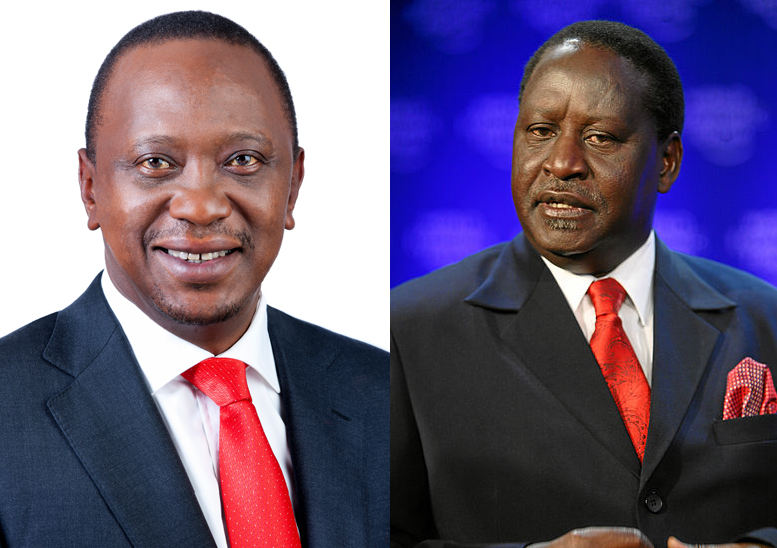

The two front runners, President Uhuru Kenyatta (left) and Raila Odinga (right). Credit: State House of Kenya/World Economic Forum.

Kenya’s general election will be contested by a large number of hopefuls, but in reality it’s a two-horse race between Raila Odinga of the National Super Alliance and President Uhuru Kenyatta of the Jubilee Party.

Unsurprisingly in a country in which the executive continues to wield a dominant influence, coverage of the campaign has focused on the personalities and records of Odinga and Kenyatta.

What does their candidacy tell us about Kenyan politics in 2017?

[Kenya’s whirlwind weekend underscores election uncertainties]

The first and most obvious lesson from the election campaign is that dynastic politics is alive and wellKenya. Despite all of the contestation, efforts and plotting of rival leaders hoping to push their own ambitions, 2017 will be fought between a Kenyatta and an Odinga, just like the elections of 2013 and the Little General Election of 1966.

The second is that ethnicity only gets you so far. In 2013, Odinga outperformed rival presidential candidate Musalia Mudavadi within his own Luhya community. This was possible because while Odinga was seen to be a credible opposition leader, Mudavadi’s dalliance with Kenyatta – with whom he formed an extremely short-lived alliance – raised concerns that he was a State House puppet. Kenyatta’s recent rehabilitation as the dominant leader among the Kikuyu community following his electoral humiliation in 2002 also demonstrates this point well.

So who are the two leading contenders?

[Why so tense? Kenya’s high stake elections explained]

Odinga, the opposition stalwart

Raila Odinga is the son of Oginga Odinga, a prominent independence leader and Kenya’s first vice president who never realised his dream of occupying State House. Like his father, Raila has campaigned tirelessly against considerable odds, and has so far been unsuccessful. He narrowly lost elections in 2007 – when many believe he was rigged out – and in 2013.

Odinga’s great ability is in being able to mobilise well beyond his own Luo community and sustain his political party, the Orange Democratic Movement, for a decade. Given that most Kenyan parties collapse within a few years, this is some achievement.

The breadth of Odinga’s support base is also impressive. In 2013, he performed well among Luhya voters in Western Kenya, Kamba voters in Eastern Kenya, and also on the Coast.

Odinga’s capacity to garner support across ethnic lines has two sources. On the one hand, he receives some votes “second hand” as a result of the efforts of his allies from other regions and ethnic groups to direct rally their communities to his cause. On the other, he’s built a strong reputation for representing historically economically and politically marginalised communities. Indeed, while he has never secured the presidency, he has contributed to political reform. Most notably, Odinga played an important role in bringing about constitutional reform in 2010 that introduced devolution and hence a degree of self-government for the groups in his coalition.

Kenyatta, born to power

Uhuru was born into power as the son of the country’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, and secured the presidency in the 2013 general election having previously failed to do so in 2002.

Kenyatta’s supporters like to say that he was born in State House, and hence born to power, although this is not actually true. But it is true that he has spent his life close to the machinery of government, and his family’s political influence and wealth give him a clear advantage in the elections. His gift is to be able to look and sound presidential when he has an important speech to make, despite his playboy lifestyle.

Although it’s tempting to see Kenyatta’s rise to power as inevitable, this is not the case. In 2002, he failed to mobilise support among his own community because he had been selected by the outgoing Kalenjin President Daniel arap Moi to be his successor. He was widely seen to be a proxy for Moi’s interests. At that point, his political career appeared to be over.

It was not until Kenyatta developed a reputation for defending Kikuyu interests by allegedly funding and organising militias in the violence that engulfed the 2007 elections that he emerged as the dominant figure within Central Province. It is for this alleged role that he faced charges (that were subsequently dropped) of crimes against humanity at the International Criminal Court. This, and his electoral alliance with his co-accused – the influential Kalenjin leader William Ruto – were critical factors in his victory in 2013.

The 2017 race

During the 2017 campaign, Kenyatta and Odinga have been a study in contrasts.

While Odinga stresses his intention to shake things up, Kenyatta presents himself as a safe pair of hands who will protect the status quo.

While Odinga plays up his image as the representative of the excluded, promising to deepen devolution and invest in poorer areas, Kenyatta emphasises building a national infrastructure and maintaining economic growth, arguing that the gains of the rich will trickle down to benefit all Kenyans in time.

These images are further entrenched by the criticisms that each leader makes of the other. The ruling Jubilee caricatures Odinga as an unprincipled thug who cannot be trusted with the fine art of government. The opposition National Super Alliance claims that Kenyatta is out of touch and only interested in serving the interests of the wealthy within his own community.

Some complain that these differences are more rhetorical than real, but one thing is clear: Kenyans have a real choice to make at the ballot box.

[Kenya’s 2017 elections will be like none before. Here’s why.]

Election outlook

The greater resources available to Kenyatta, along with the more professional team around him, mean that the opposition faces an uphill battle. Moreover, government interference with the media – which is regularly intimidated – means that while election reportage is vibrant, some of the stories that would most hurt the government don’t make it onto the front pages.

It’s therefore not surprising that Kenyatta enjoys a small but significant lead in the polls. A series of surveys conducted by different companies using different samples have put him on around 48% of the vote, with Odinga on around 43%. These polls suggest that about 8% of Kenyans remain undecided. This suggests that Odinga can still win, but to do so he will have to capture the vast majority of “floating voters” in the last month of campaigning.

If undecided voters divide equally between the two main candidates, Kenyatta looks set to end up on around 52% – surpassing the 50%+1 threshold for a first round win – with Odinga on 47%.

Given this, the record of no sitting Kenyan president ever having lost an election may survive for a while yet, despite the momentum behind the opposition. Although the country has made real democratic strides with its new constitution, the advantages of incumbency remain formidable.

This article was originally published here on The Conversation. The Royal African Society is holding a pre-election briefing on Kenya, Wednesday 2nd August, in London with Njoki Wamai, Justin Willis, Edwin Orero, Keni Kariuki and Agnes Gitau. Tickets £5 / free for RAS members. Book here.