Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis is escalating. Here’s how it could be resolved.

Improving decentralisation countrywide would appeal to Anglophone protesters, but without seeming to give them special treatment.

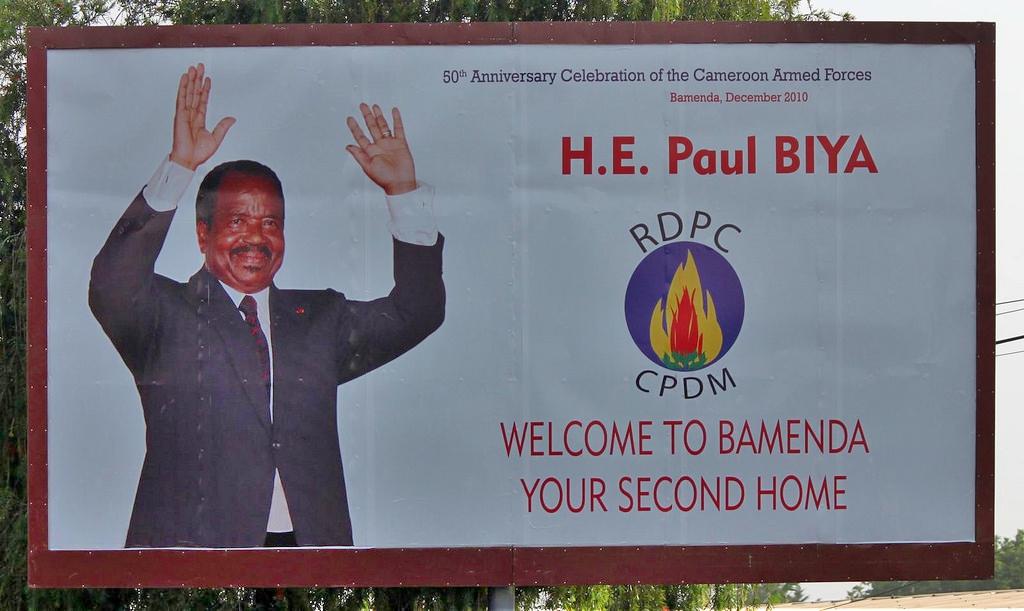

A poster of President Paul Biya in Bamenda, a city in one of Cameroon’s Anglophone regions. Credit: Carsten ten Brink.

On 22 September, massive protests across Cameroon’s Anglophone regions brought an estimated 30-80,000 people onto the streets. These were far larger than those which sparked the crisis at the end of 2016. In clashes with security forces, three to six protesters reportedly died – the first deaths in the crisis since January.

The demonstration came in the context of an already-deteriorating situation marked by the use of homemade bombs by militants, the failure to open schools for a second year due to ongoing strikes, and mounting incidents of arson.

The violence followed incidents in Western capitals throughout the previous month. On 1 August, a meeting in Washington between a senior delegation from the Cameroonian government and the US-based diaspora descended into farce, interrupted by angry exchanges. In Belgium, the delegation’s meeting was interrupted by violent scuffles. In South Africa, activists who had been denied access broke into the meeting, which was then cut short. The same happened in Canada, where the flag of Ambazonia, the putative homeland of Anglophone secessionists, was raised inside the High Commission. And in the UK, the invite list was reduced to a select and vetted group.

The resurgence of violence demonstrates that the roots of this crisis run deep, as detailed in the recent report from International Crisis Group, and that the measures taken by the government so far have failed to address grievances. By jailing the legitimate representatives of the Anglophone movement back in January, the government may have even played into the hands of the more radical elements.

As 1 October approaches, the anniversary of reunification of Anglophone and Francophone Cameroon, some militants are preparing to declare independence. If serious measures are not taken and a willingness to start genuine dialogue not forthcoming, protests are sure to erupt again, and could be worse this time.

Anglophone grievances

Cameroon’s Anglophones make up 20% of the population. Most live in former British territories in the North-West and South-West regions. Their anger was sparked off in 2016 by the government’s refusal to respond to Anglophone lawyers who were aggrieved at the nomination of magistrates who neither spoke English well enough nor were trained in British common law.

After demonstrations were met with sometimes brutal force, teachers and students joined the growing movement, adding similar concerns about a way of life being progressively taken over by Francophone practices. At least nine people have now died in subsequent violence, and militants have frequently used sabotage and arson.

After negotiations broke down in January of this year, the government imprisoned the most prominent Anglophone activists alongside many others caught up in protests. They also cut off the internet in Anglophone areas for three months, causing huge damage to the economy.

[Cameroon sabotages own digital economy plan with internet shutdown]

Broken promises

Anglophones feel marginalised and often humiliated in their own country. Many look back to the independence era. In February 1961, Anglophone Cameroonians, then under British rule, voted in a controversial UN-organised referendum to re-join francophone Cameroon. For the previous 40 years, they had been ruled by the British following the defeat of Germany, the first colonial power of all of Cameroon, in the First World War.

The constitutional conference which followed in July 1961 was hopelessly one-sided. A weak Anglophone negotiating team sparred with a Francophone side which had already gained independence and had strong support from its former colonial power, France. The result was a series of vague promises that Cameroon would be an “equal federation” in which the English language and customs derived from British rule would carry equal weight at the federal level.

The reality was anything but. First, in October 1961, only weeks after Anglophone Cameroon joined the federation, President Ahmadou Ahidjo (a Francophone who enjoyed very close ties to France) reorganised the country from two federal states to six regions. With the regions’ powers unclear, this move deliberately introduced confusion into local governance that has remained to this day.

Ahidjo then named federal inspectors in each region, who enjoyed more power than locally elected politicians. In 1965, he banned opposition parties, forcing all political aspirants, including Anglophones, into his orbit. At the same time, he chipped away at customs and institutions the Anglophones had inherited: their currency was discarded; membership of the British Commonwealth was not considered; imperial weights and measures were dispensed with. In 1971, through a national referendum, Ahidjo abolished federalism altogether, crushing the now fading Anglophone hope that they could enjoy a partnership of equals.

For three decades, Anglophones, like many of their Francophone compatriots, cowed by the brutal civil war that had raged in Francophone Cameroon in the 1960s, more or less accepted their lot. But in the 1990s, political freedoms blossomed again, and Anglophones were encouraged by the fact that the most important opposition party to emerge at the time, the Social Democratic Front, had one foot, if not two, firmly planted in the Anglophone region.

But as President Paul Biya, in power since 1982, slowly crushed hopes of pluralism and freedom, Anglophone frustrations grew again. Movements calling for a return to federalism, and even outright secession, proliferated. For many years these groups were largely based in the diaspora, hence the anger seen in Western capitals. But the movement of 2016 and 2017 has more domestic roots, based on widespread anger on the ground.

Decentralisation as the start of a sustainable solution

After repressing the movement at the start of the year, the government has made some concessions, most notably restoring the internet in April and allowing the release of some (but not all) detained activists in August. But Yaoundé continues to treat the Anglophone movement as subversive and illegitimate. Militants were imprisoned in January for publicly discussing federalism, a discussion which should be perfectly allowable. The government refuses to acknowledge widespread feelings of marginalisation and humiliation.

To reach a sustainable solution, especially important with national elections looming next autumn, the government must start by acknowledging the well-founded grievances of Cameroon’s Anglophone regions. For trust to be re-built and maintained, concrete actions need to be taken.

Decentralisation is the most promising and is set out in the new constitution of 1996 and in laws of 2004. Since then, mayors and local councils have been elected, and the law stipulates that they should have their own budget and be responsible for local public services. But even these vague legal texts – for example the percentage of locally raised taxes to be devolved to local government is not specified – are not respected in practice.

Regional councils, led by elected regional presidents, are foreseen in the constitution, but have not been created 21 years on. Shortly after creating local councils, the government created its own delegates nominated by the president and accountable only to him. In day to day matters, the delegate has far more power than their elected counterparts, even those from the ruling party.

The problem of partial decentralisation is a frustration in all parts of the country. Improving it countrywide would have the distinct advantage of appealing to the Anglophones without seeming to give them special treatment. Regional councils should be created, or else a national debate started on whether they are needed. Local councils should have the powers over public services foreseen in the law and autonomy over their budgets.

Improved decentralisation would, if handled properly, reassure Anglophones that they have control over their own legal and educational system, rather than feeling that any gain they make is subject to the whims of central government.

Of course administrators in Yaoundé, and President Biya himself, who has created one of the world’s most centralised decision-making machineries, would lose some of their discretion. But the up side would be significant: a reinvigorated sense of national purpose and cohesiveness and less risk of renewed violence in Anglophone areas.

Love to always be informed.

Mr. Moncrieff, you capture this problem succinctly. The idea that this problem was going to stay latent forever was just pure fantasy by the Biya regime. Having grown up in this odious system and suffered the humiliations described, there is no going back. We cannot be colonized forever.

Your article and insight is quite conclusive, more than most in fact, but most fail to mention the steps the government has taken to meet the Ambazonians, by creating whole bodies to negotiate all of the grievances which the anglophone lawyers had raised, and secondly, the release of most of the detainees recently. It is clear that the Ambazonians don’t want any negotiation whatsoever but want their own independant state. Also, the fact that many anglophones are not in agreement with them (Ambazonians) or are in between and don’t know what to believe or do. There are other groups who have risen up, the main one being, ‘English Cameroon for a United Cameroon, who are trying to work with the Anglophones to send their children to school and to solve these problems in a peaceful way.

The other side which the Ambazonians haven’t told the press is how much violence they have incited- even to the point of having their ‘boys’ beat up children who wanted to go to school; that’s why parents are afraid to send children to school- it’s not that they don’t want to- they are afraid of what will happen to them. Such as recently, in Sacred Heart school bombs were set off in school, and other cases of schools being burned.

The Ambazonians only want their own state and are prepared and urging citizens to take up arms and fight for it come Oct 1. In my opinion, they are a terrorist group who is holding the Anglaphone community hostage to get what they want.

Their region contains most of the rich agriculture, and also oil off the coast of Limbe so that is another factor to consider.

It is so sad. because Cameroon was known to be a country of peace and now these few radicals are turning it into a war zone!11

Moncrief, thanks for your well-intentioned but misguided recommendation of decentralization as a solution to the Southern Cameroons problem. While you accurately noted the changes in the nature of the protests against La Republique, your choice of words failed to keep pace with the current climate of the struggle. It is no longer and Anglophone problem, it is a Southern Cameroons problem and they are not fighting against marginalization but against annexation and illegal occupation by La Republique du Cameroun. Nothing short of a referendum to restore the independence of Southern Cameroons will be accepted at this point.

Great article, the wheels of change will not stopped by any piece meal appeasement by LRC. We are two different people and need to stay separate. They loot our resources for nearly sixty years, no development nor increase quality of life and they still talking about southern Cameroon staying in this useless marriage? Any sensible person with a vision will agree that after almost sixty years it did not work and divorce is the ultimate solution. These guys have done this over and over again, they just enjoy going to New York for the UN session and do nothing but lavishly spend resources that could have been used ameliorate and to improve the lives of many in Cameroon. These morons shop on Fifth avenue at many trendy and upscale shops, stay in very lush hotels, I just cannot understand this. It is shameful and sad, it is pathetic

I could not leave this forum with out spitting out my saliver; the Biya regime has for long been adamant on issues that concerns the two English speaking regions of Cameroon. in as much as many even our French speaking brothers acknowledge the fact that there is an anglophone problem, most of Biya’s suburdinates still want to fill in the gap blatants lies by telling him all is well,, the few previlledged english speaking citizens who manage to share a piece of the cake go open on air radio and TV to tell the masses that there is no such thing as an Anglophone problem. I know the problem of cameroon has ever been the will and the lack of pronouncing issues the way it is being felt on the field. for me I see this becoming a revolution and in a revolution the first man standing will certainly not be the last man standing…. lets watch how events unfolds

The history of Mr. MONCRIEFF’s article is concise and accurate. His proposed solution to the Anglophone problem is naive. If the president had immediately responded with humility to the lawyer/teacher protests last November, the writer’s suggestions may have been possible (while only kicking the can of the real problem down the road a few more years). However, once pictures of dead, unarmed protesters, and multiple videos of compliant youths being mercilessly beaten by “security forces” began to circulate, the idea of a federalization solution became wishful thinking. This article’s tidy little proposals are simply not a viable option after the Biya regime arrested the consortium members earlier this year and called them “terrorists.”

As rightly stated by my brother Moncrief, your misguided recommendation of decentralization as a solution to the Southern Cameroons problem will not solve the problem on the ground at the moment. I even doubt if you truly understand the situattion at hand.

Thank you

This sounds like the Nigerian -Biafran case currently going on in Nigeria. I stand to be corrected though.

comrades we all know that President Biya is a “puppet” to France. France have dominated West Africa for hundreds of years as a conqueror plus as a European friend who robs West Africa by every method possible. France intent is to cause chaos while it plunder. It require it puppet as is Biya to keep their nation very very much underdeveloped as is Cameroon especially in light of Cameroon resources plus wealth. France also require of its puppet to oppress its people as is done in English speaking Cameroon. Being France have been in West Africa for hundreds of years as evil European friend offering guidance how is it not one city in West African nations where France dominate despite their riches is not as developed as any city in France having 100,000 people or more. There is something wrong with that condition. It is that incompetent Biya relies on his partnership with France to keep him in power as oppose to demonstrating good leadership by giving his people world class modern living conditions. If his daughter while in college in California (USA) is able to spend 400 US dollars on a limousine taxi ride surely there is adequate funds for all non rich of Cameroon to live in modern housing with essential modern conveniences such as electricity, running water plus sewage. If not after excess a generation of Biya incompetent or mediocre at best leadership he is expendable so that Buntu (negroid) people of Cameroon may shed their oppression plus efficiently develop Cameroon to modern living Buntu nation it should be instead of a puppet to France. We hope Biya soon leave office by democratic means however, for such oppressors timely removal by any means necessary is not ruled out. Very much sincere, Henry Price Jr. aka Obediah Buntu IL-Khan aka Kankan aka Gue.

The crisis has now gone too far. Moderates making their entry into the field of play everyday. As Mr. Biya continues to delay with organising an inclusive dialogue, many more people are dying and many more being radicalized.