“I saw myself as I giant”: Tackling a crisis of masculinity in Kenya

A Christian-infused programme urges prison inmates to look beyond traditional gender roles. But is a godly masculinity better than a toxic one?

George dances with other inmates at the start of the Man Enough workshop. Credit: Thomas Lewton.

Kamiti Maximum Security Prison’s reputation precedes it. Located on the outskirts of Kenya’s capital Nairobi, several anti-colonial leaders were executed here during the struggle for independence and it has long known for its brutal conditions.

This afternoon, however, a group of inmates beyond the foot-thick metal-reinforced wooden doors have spent the last couple of hours laughing and smiling. Most dressed in striped prison uniforms, around twenty men – many convicted of murder, armed robbery and rape – have been behaving more like excited children at Sunday school than hardened criminals.

Sitting in the sunshine of the prison courtyard, one of the men speaks up. “My name is George, and I am born again”, he says, beaming. He is wearing sunglasses and the blue jumpsuit given to the best behaved prisoners.

“It is now my 18th year in prison and I came in for murder…I came in a very bitter person, someone who was ready for revenge. I even thought of taking my own life.”

George, 50, goes on happily to explain that he now sees things differently and has learnt to empathise with others.

Anthony, who was convicted of murdering his brother in a family dispute, tells a similar story. He says he was also often violent on the outside, especially towards women, but says his understanding has now changed.

“I saw myself as I giant,” he says. “Men are known as the kings, so when a man has no funds for the family he feels low esteem, and that makes him enter into crime”.

Inmates listen intently during the workshop. Credit: Thomas Lewton.

These inmates are participating in Man Enough, a ten-week programme that, according to its website, “seeks to restore the honor of manhood”. The initiative began in churches about eight years ago, but has since been rolled out in schools, corporate workplaces and prisons.

According to Simon Mbevi, a pastor and the project’s founder, Man Enough is a direct response to a crisis of masculinity facing Kenyan men today as societal norms and roles have shifted. “Lots of men have wives and girlfriends who are earning a lot more than them and struggle with that because they think that what you earn is what gives you power,” he says. “They say ‘this woman has more power and so she won’t respect me’. What we have been saying is that we don’t respect each other because of the positions or the roles we play, but because we are human beings”.

Man Enough attempts to teach participants to move beyond traditional gender roles. “What we will be teaching them is that both of us are providers,” says Mbevi. “You do your part, they do theirs. We work together as partners.”

[Meet some of the men redefining masculinity in Kenya]

Pastor Simon Mbevi, the founder of Man Enough. Credit: Thomas Lewton.

80% of Kenya’s population is Christian and the religion is central to Mbevi’s idea of positive masculinity. He has said previously that we are beginning to see a “responsible, godly masculinity rising up across East Africa”.

Christianity may not be known for its gender progressive ideals, but the pastor argues that his programmes work because they operate within a framework most Kenyans support and understand. He says that even those of other religions such as Muslims would respect a Christian programme more than a secular one.

“The church still has a lot of integrity in the community,” he says. “I think the credibility of the church and church leaders should be used to speak openly against negative masculinities.” He believes that religious leaders should talk more about gender equality and notes that some even encourage domestic violence rather than condemn it.

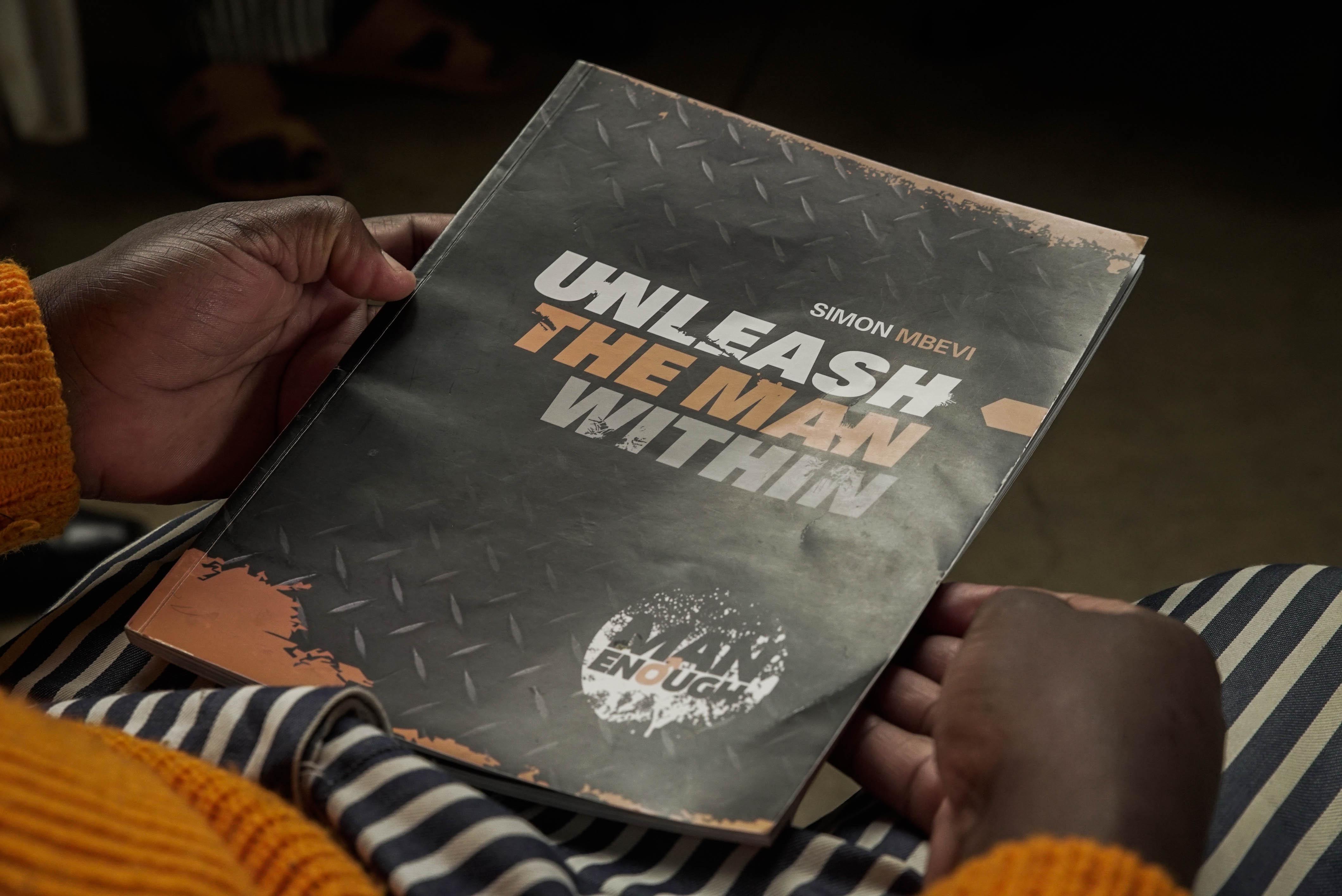

A participant reads the Man Enough manual. Credit: Thomas Lewton.

The Man Enough programme therefore uses religion to promote a new kind of masculinity. Yet at the core of its vision of a “godly masculinity”, there remain some highly conservative ideas. Almost all the inmates taking part at Kamiti prison, for instance, refer back to the biblical story of Adam and Eve as their basis for understanding relations between men and women.

“The role of a woman is to help a man because God himself during creation said it is not good for man to be alone, ‘I will make him a helper’”, says James, who is serving a life sentence for murder. Shadrack, inside for armed robbery, adds that the Bible has taught him that “a woman is only there to help me”. He expresses shock and confusion at the end of our interview when he discovers that we are “not saved”. “But you should be saved”, he advises.

Illustrating the biblical basis of a godly masculinity. By Charity Atukunda.

Mbevi’s language of “Wounded Warriors” and “Heroes” is similarly tied to the macho expectations at the heart of Kenya’s crisis in masculinity. Meanwhile homosexuality is, according to the Man Enough handbook, “something to be corrected”.

In many ways, a godly masculinity has several similarities to a traditional toxic one. It may not pave the way for genuine and sustainable gender equality to take root. Yet in a country where the Bible remains the moral compass for most, Man Enough is a powerful tool for getting men to question some of their most damaging assumptions. And for inmates at Kamiti prison like George, it has helped them come to terms with their past behaviour.

“I’ve now been able to look at my actions from the perspective of another person”, he says.

This story is part of Big Men, a European Journalism Centre project telling journalistic stories about men, masculinity and gender equality in East Africa.