Cameroon elections: President Biya set for routine, if Pyrrhic, victory

Rather than consolidating the president’s 36-year rule, the upcoming elections could heighten frustrations with it.

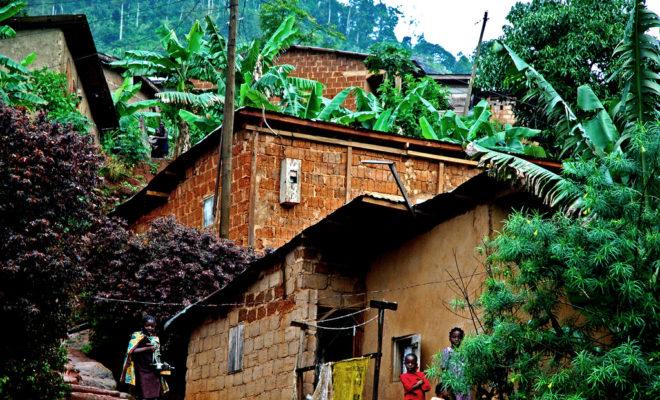

In power since 1982, are President Paul Biya’s days in office numbered? Credit: Alvise Forcellini.

When Cameroon votes in presidential elections on 7 October, President Paul Biya will be relatively untroubled by the possibility of losing power. Despite a record of corruption and the mounting crisis in the Anglophone regions, a repeat of the 2011 polls in which the ruling RDPC garnered over 75% looks likely.

However, while Biya looks set to renew his mandate at the ballot box, this victory is unlikely to bring much solace to the president or the Cameroonian people. Contrary to most elections, this one could in fact raise tensions and exacerbate feelings that Biya’s rule is illegitimate.

In Cameroon’s upcoming election, the odds are stacked heavily in the ruling Rassemblement démocratique du Peuple Camerounais’ (RDPC) favour. Even putting aside the very real possibility of rigging, the incumbent’s access to state machinery and vast patronage networks – built up over Biya’s 36 years in power – give him a huge advantage.

This position is further strengthened by a divided opposition. There have been repeated calls for the formation of a coalition, but this has not materialised. This means that Biya faces eight separate political groupings. These range from the well-established Social Democratic Front (SDF) and its candidate Joshua Osih, to the brand new NOW! movement headed by lawyer Akere Muna. Some opposition figures have offered credible solutions to Cameroon’s ills, but it is difficult to see how they can mount a credible challenge to the RDPC without pooling their resources and voters.

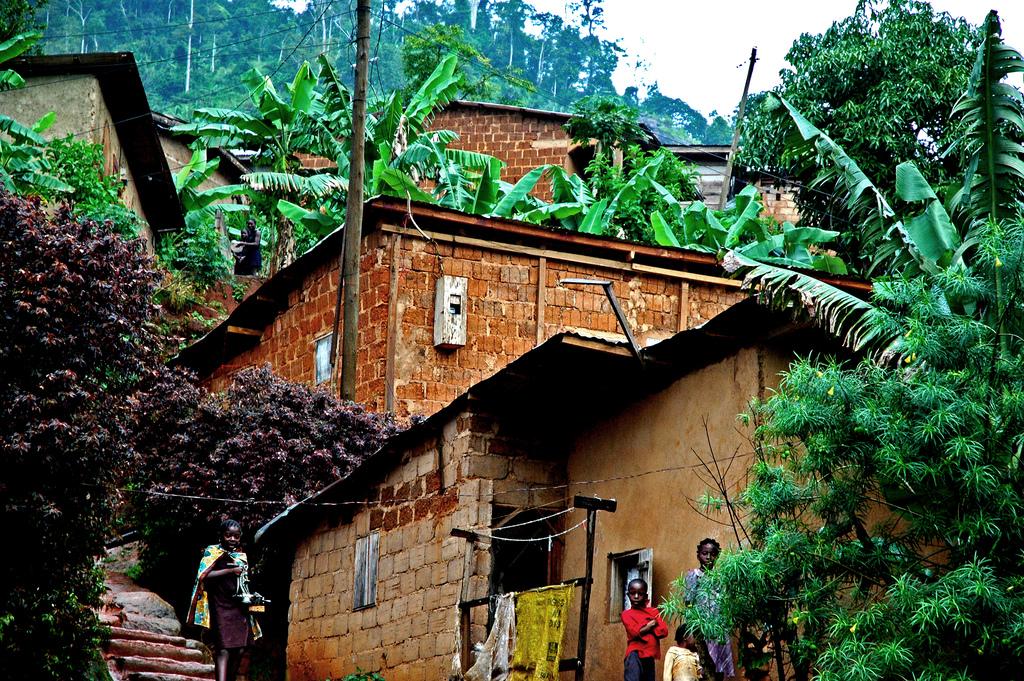

Cameroon’s election will be held against a backdrop of instability. The army is battling Boko Haram militants in the Far North and Anglophone separatists in its western regions. The latter dispute has escalated dramatically over the past two years. It first came to a head in 2016 when lawyers and teachers frustrated at the perceived imposition of French in courts and schools went on strike. This soon led to spiralling protests and deadly crackdowns. As tensions deepened, separatists declared an independent state of Ambazonia and Cameroon became engaged in a fully-fledged guerrilla war.

With the election coming up, Anglophone separatists have vowed to prevent voting in territories under their control. It is in these regions that major opposition parties enjoy their greatest support. Since 1992, the majority of the main opposition SDF’s support has come from the western regions. Both Osih and Muna, the two most prominent opposition candidates, hail from these English-speaking areas.

On the one hand then, disruption to voting in Anglophone Cameroon could be seen as an electoral boon for Biya. Concerns over the country’s instability could also lend greater force to his party’s promise to re-establish order.

But on the other, the unrest threatens to undermine Biya’s prospective victory by delegitmising the poll and its results. The president has insisted that voting will go ahead despite the separatists’ intentions and promised that their “mad dream will never come to fruition”. But the instability in Anglophone regions risks disrupting a process that the opposition is already decrying as unfair.

The SDF has described the placement of polling booths in military barracks and presidential palaces as unconstitutional. It has demanded the government explain how it will enable the huge numbers of displaced Cameroonians to vote. Meanwhile, mass voter apathy – with only 7 out of a total 13 million voters registered to vote – suggest that many citizens see the electoral process as illegitimate to begin with.

If huge portions of the populace are unable to vote due to the Anglophone unrest, the election may lose even more of its perceived validity. If this happens and the re-election of an unpopular Biya is deemed to have been unfair, it could spark frustrations beyond the Anglophone regions.

It is true that, after the 2011 elections, allegations of fraud did not prevent Biya from continuing to rule with his popular mandate broadly intact. But this time, the circumstances are decidedly different. The threat of Boko Haram in the Far North is simmering. The Anglophone unrest is reaching fever pitch. And – as Cameroonians have watched their counterparts in other African nations expel their own long-standing strongmen in the last few years – patience with Biya’s corrupt 36-year rule is ever thinning.

[Cameroon: What one man’s 17-year ordeal tells us about Biya’s regime]

These problems will not lose President Biya the election – in fact, disruptions and apathy could help him win it – but in retrospect, he may look back on this as a Pyrrhic victory.