“Music exposes thieves”: Meet Bosmic Otim, ‘northern Uganda’s Bobi Wine’

In the north, a different popular singer articulates the people’s widespread frustrations and recent memories of violence.

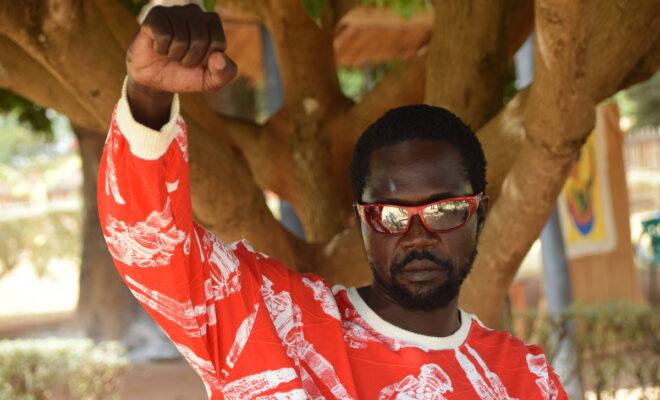

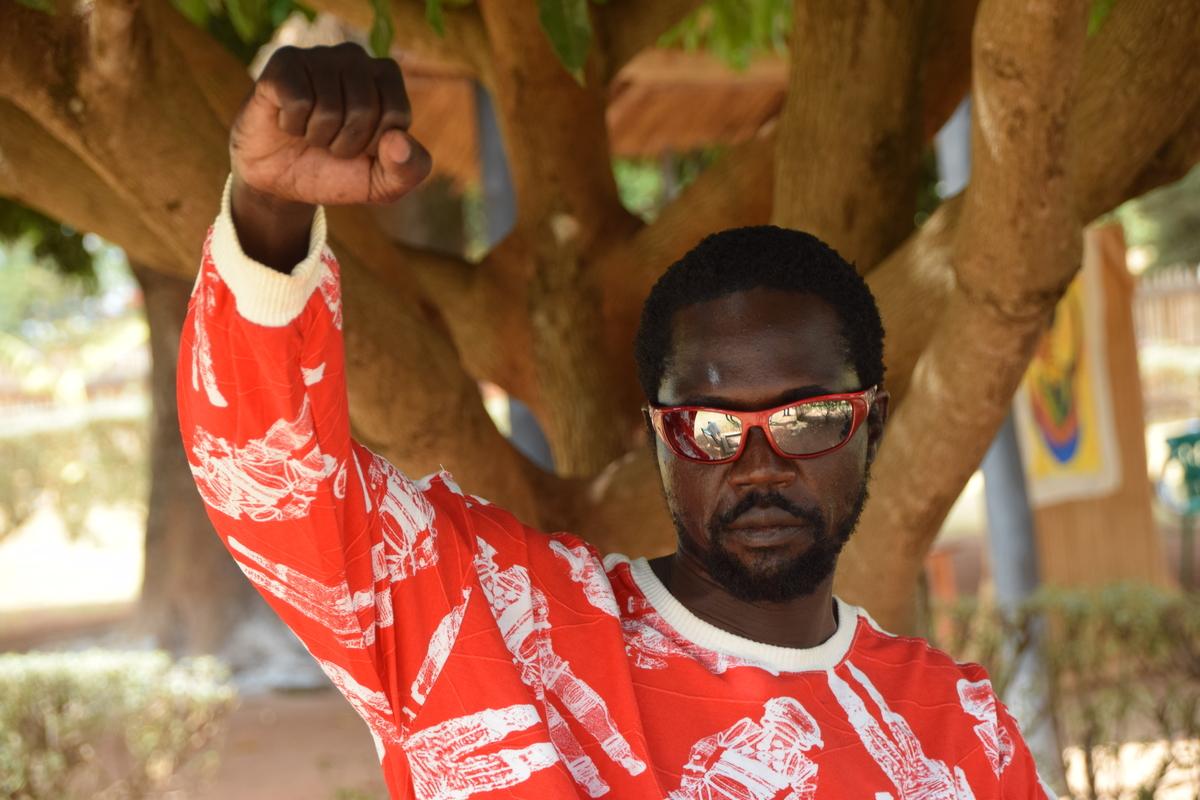

The songs of Bosmic Otim are played across northern Uganda, from buses to bars. Credit: Liam Taylor.

Garbed in red designer jeans, shirt and a jacket, Bosmic Otim sits under a tree, scrolling through his phone. Every inch the popstar, he is prepared to make us wait. Half an hour later, his entourage show up with a video camera. They record all his interviews, he says, for “future reference”.

Bosmic, 34, is barely known outside northern Uganda. But here in the Acholi region, he is a superstar, his songs played everywhere from buses to bars. In 2006, his music became the soundtrack to peace as it returned after two decades of war between the Ugandan government and Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). Today, it chronicles the faltering reconstruction with songs of corruption, land, greed and inequality.

“Music is more powerful than the gun,” says Bosmic. “Music is more powerful than politics.”

In Uganda, it sometimes seems that way. The country’s most talked-about politician is Bobi Wine, a popstar from the capital Kampala. His songs are highly critical of the government and, since winning a parliamentary by-election in 2017, the new MP has been a thorn in the side of President Yoweri Museveni. In response, the government has detained Wine, allegedly beaten him in custody, cancelled his concerts, and now has plans to vet his songs.

[Bobi Wine: Why the Ugandan regime is so rattled by the popular musician]

[Generation gap: What #FreeBobiWine tells us about Ugandan politics]

In the north, however, few people understand Wine’s lyrics, which are largely in Luganda, the language of the central region. Instead, it is Luo-language singers like Bosmic – the self-appointed “ambassador to the northern region of Wine’s People Power movement” – who ventriloquise the youth’s frustrations.

Bosmic may not inspire the same devoted following as Wine or command the same national recognition, but his indignant voice articulates the marginalisation that many Acholi feel. As he tells it, music is an almost primeval force that comes before and above politics.

“Music exposes wizards,” he says. “Music exposes thieves. Music exposes thugs.”

In Acholi culture, music has long been used to speak truths. Even Okot p’Bitek’s wer pa lawino, the long poem about culture and colonisation widely-considered to be the greatest work of Acholi literature, is styled as a song.

Bosmic follows in this rich tradition. As a child, he mastered traditional instruments like the nanga (zither) and adungu (arched harp). Later, he encountered the music of South African reggae star Lucky Dube, who Wine also cites as an inspiration. Dube’s songs about apartheid resonated in northern Uganda where the government had ordered over a million people into camps as it fought the LRA.

Bosmic recorded his first video in one of these crowded settlements. Soon after, he was travelling from one camp to another, often hired by NGOs to sing about AIDS, domestic abuse and alcoholism. He was the dreadlocked avatar of three traditions: Acholi poet, reggae prophet, humanitarian rent-a-mic.

LRA fighters would even phone in to radio stations to request Bosmic’s songs, remembers Steven Balmoi, a presenter on Mega FM. The hit “Peace Return”, a reggae-flavoured plea to politicians, became an anthem of the Juba talks between the government and the LRA. Those negotiations failed, but peace did finally return to the north as the rebels moved elsewhere from around 2006.

More than a decade on, the wounds of the war have not healed. In southern parts of Uganda most people are too young to remember the war that brought Museveni to power. But in the north, the president has the opposite problem. Almost every young adult spent part of their childhood in a camp. They remember the violence and they blame their suffering not just on the LRA, but also the Ugandan army.

“Museveni said it’s Kony and Mr Kony said it’s Museveni,” sings Bosmic in his 2018 song “ICC”. The video cuts to talking heads describing army atrocities, spliced with pictures of corpses and generals. The chorus asks: “Between the government and the rebels, who is to blame for the massacre of our people?”

In conversation, Bosmic runs through a familiar list of lamentations faced by people today: the land of the Acholi has been grabbed, their cattle stolen, their children robbed of an education. “We feel cheated,” he repeats, like a mantra. “After 20 years plus then the whole world started shouting, ‘northern Uganda is peaceful at last, peaceful at last’. But do they know how much we have lost?”

In “Mac Onywalo Buru” (Fire Begets Ash), released last year, Bosmic turns his wrath on northern politicians, including ministers and the sons of former presidents, who have worked with the government.

“They are siding with outsiders to fight their own people,” he sings in Luo. He adds that the late presidents Tito Okello and Milton Obote, both from the north, would hang themselves if they could see the treachery of their sons.

For many people, that went too far. Government officials in Bosmic’s home town of Kitgum banned the song. Balmoi says that he wouldn’t play it, because Mega FM has a policy of not promoting hate.

Bosmic’s personal attacks on politicians and musical rivals also alienated some listeners.

“I used to like the old Bosmic more compared to the new one of these days,” says Aisha Ataro, who runs a business in the town of Gulu. “Bosmic used to talk about issues that really affected the common people but these days he is too political and he sounds too bitter.”

Musically, Bosmic has been “jumping from one style to another”, says Benedict Ojok, a music scholar and trainer at St Joseph’s College Layibi. But the power of music is undeniable, he adds. “Politicians are now starting to realise that passing messages through music is louder and reaches further to the audience than [just] talking to people in a rally”.

Like Bobi Wine, Bosmic has shaved off his dreads and started studying. Is there truth in the rumours that he will follow Wine into politics?

No, he says eventually, but chuckles that his fans already call him their MP. In the north, at least, he is a household name, while Acholi communities abroad have lauded him for his “peace songs”.

His recent release, “People Power”, certainly hints at bigger political ambitions. It opens with a spoken exhortation in English, in the style and cadence of Wine.

“Otim is a hero,” he sings with characteristic humility in a refrain that brackets himself with Wine and Nelson Mandela.

And yet, when he slips into Luo, bleaker lyrics cuts through the upbeat melody. “I am so overwhelmed by hatred that I feel like beating someone,” he sings, “like kicking someone. And kick, then kick and kick.”

It is a sentiment at odds with Wine’s own anthem du jour, “Tuliyambala Engule”, in which a pastor tells listeners to “use peaceful means” and “don’t fight”. But then, as Bosmic notes, the experience of the north is not the same as the rest of Uganda’s.

“Those who killed people in northern Uganda must know that the souls are still crying in the bush,” he says.