Egypt: When football stadiums become military zones

At the recently concluded AFCON, Egypt’s politics of control against its own fans was on display in the empty stands.

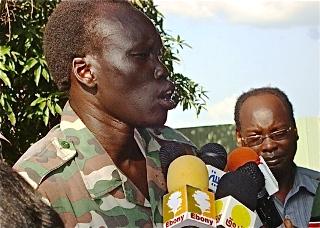

The Nigeria vs. Algeria AFCON semi-final game between two football heavyweights. But you wouldn’t know it by the looks of the stadium. Credit: Temi Egbejule

A few weeks ago while in an Uber, running errands in the debilitating heat of Cairo’s noon, the driver and I started to discuss why he no longer watches football. He stopped after the Port Said massacre of February 2012 where 72 Al-Ahly fans were killed, he said. They were attacked by rival football fans. He witnessed the massacre in the stadium and lost six of his close friends.

“I can’t get myself to watch football again. What does it mean that people are just going to a match and then they get killed?” he asked. “I thought that football has nothing to do with politics but after Port Said I realised everything about football is politics!”

This young man’s apt words describe precisely what is happening to football in Egypt. Since 2013 and the army’s takeover of power, the country’s most popular sport has undergone unprecedented changes. This transformation manifests in the empty terraces during the local Premier League and National Cup matches, which fans have been banned from attending since 2015.

It is also seen – albeit less obviously – in the securitisation of the sport’s superstructure and infrastructure by the army and security apparatus. Among other things, security forces have been acquiring sports media, specifically TV channels, in the past few years. Through this, they have been influencing the discourse around football by vilifying organised fans group known as The Ultras and by glorifying the regime.

The recently concluded Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) acted as a catalyst in this process. The tournament is a good lens to examine these less noticed changes, especially given the tournament’s failure to attract thousands of middle-class fans, as the state had hoped, and recapture the same triumphant image of AFCON 2006 when the country last hosted the games.

Stadiums as a site of army control and power

To realise the scale of change in the infrastructure of football, one has to look at Egypt’s history in hosting AFCON. A striking shift in the ownership of the hosting stadiums has occurred in the past two decades from the state to the army. Stadiums have always been the locus of power. Their history is living proof of how the different regimes have cultivated power and garnered popularity.

Egypt has hosted five AFCON tournaments: in 1959, 1974, 1986, 2006 and 2019. The 1959 tournament was very small, but in 1974 and 1986 all the hosting stadiums belonged to the state. In 2006, one third of stadiums were owned by the military. In 2019, half are army-owned.

According to an Egyptian sports analyst who spoke on the condition of anonymity, the dynamics behind the military’s increased role in football infrastructure has changed over the years. “The army’s interest in football in general and the stadiums in particular was not always for the same reasons,” they said. “Before the 2011 uprising, it was mostly because of economic interests and for investment reasons; the army saw stadiums as a profitable business. But after 2011, the army’s control over the stadium is mainly for security reasons.”

Football fans as the opposition

In this context, security seems to mean controlling the fans.

“These stadiums, according to the law, are military establishments,” said a human rights lawyer who also requested anonymity for fear of state persecution. “If for any reason, riots erupted in the stadium, the arrested fans would be, by law, subjected to military trials.”

Before 2011, organised fans were usually arrested after riots or before big games, but then released. Since 2011, however, there has been a growing trend of subjecting the Ultras to trial. In 2017, 235 Zamalek fans went to military court following the so-called Borg Alarab incident. In the past few years, hundreds more have been arrested and accused of rioting, joining a group that was unlawfully established (the Ultras), attacking public servants, or damaging public properties. They have also been denied access to stadiums, the exception being regional and international matches where the army has to abide by the FIFA and CAF rules and allow fans to attend.

A renowned local journalist who spoke on the condition of anonymity said: “The state in general has zero tolerance to the Ultras and organised fans. They are not considered fans anymore but deemed a political power. Even the non-politicised and non-organised fans are also being feared. The state does not want any gatherings of any kind in public places even if it is a football match. Hence, the failed version of AFCON we are witnessing, where most of the matches are almost empty.”

AFCON caught in the middle

The absence of fans during different matches was so startling in recently-concluded tournament that it was even reported by the pro-state Al-Ahram website. Experts have attributed the lack of attendees to many factors, including the high prices of the tickets and often complex process of online registration and getting a Fan ID. Many journalists and experts who spoke to African Arguments also talked about the government pressuring private sector corporates to buy tickets en masse, which partially explains the paradoxical phenomenon of fans finding matches sold out despite the terraces being empty. But the reason underlying these is the attempt by the army to control power (and optics).

The journalist explained: “Throughout history, organising big sports events was used by authoritarian regimes to whitewash their image. This has happened in Germany in 1936 with the summer Olympics and with Argentina in the 1978 World Cup, but this championship is not even succeeding in doing that.”

Experts agree that the army’s intervention with football infrastructure should be read in the wider context of the military’s intervention across Egypt’s economy and society. In an article published in 2011, Zeinab Abu Elmagd, a researcher on militarisation of business in Egypt, estimated the army’s share in the economy to be ranging between 25-40% with economic interests in fields as diversified as food production, gas stations and plastic manufacturing.

Only time can tell the real motives behind this increased military presence in the football industry, whether it is mere control or also a way to generate profit. But for the time being, Egypt’s stadiums are turning into military zones, while attending a football match has become an activity that could end in military trial.

The author is a researcher in Egypt. They wished to remain anonymous.