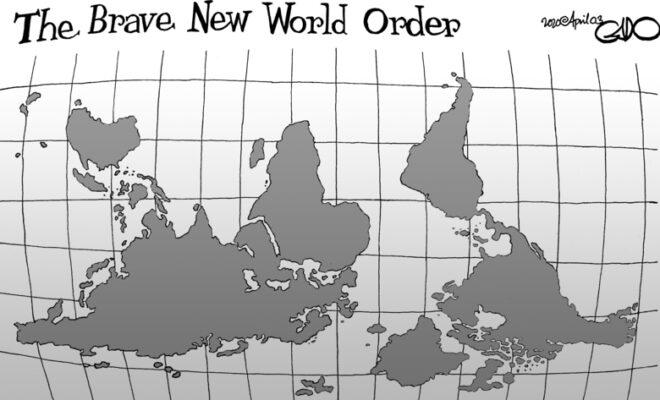

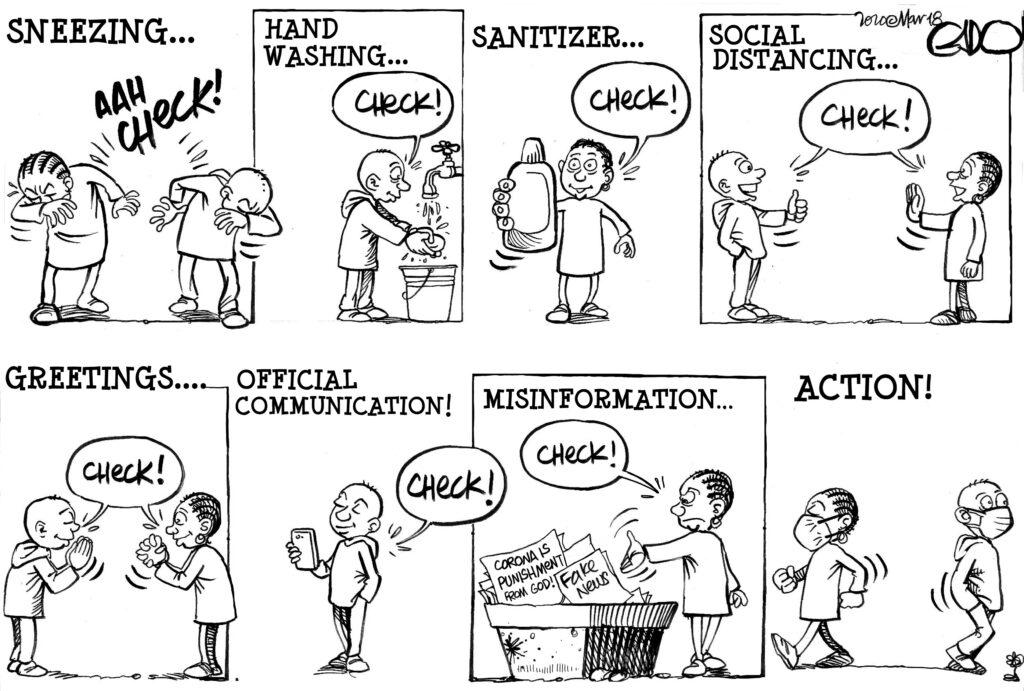

In February 2020, many analysts assumed Covid-19 would arrive in Africa before it reached Europe. From the outset, international humanitarian experts have worried about how the virus would impact Africa. While the long-term implications have yet to be seen on the continent, Covid’s impact in Europe – with hundreds of thousands of cases – is undeniable, creating as famed cartoonist Gado illustrates, a ‘new world order’. There is, of course, a certain irony to how these events have unfolded, particularly since African social and cultural norms are often blamed for outbreaks and epidemics on the continent.

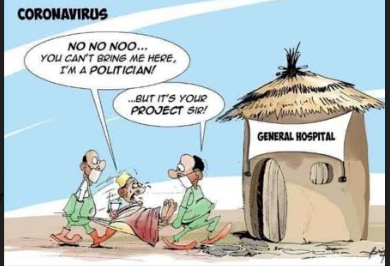

Humour, particularly in the African context, has frequently been analysed as a source of social commentary and political resistance. Social commentators and comedians use different avenues – cartoons, standup comedy, memes, televised satire shows and impromptu everyday humour – to challenge politicians and subvert the status quo. Nigerian cartoonists, for example, have long poked fun at their politicians, but particularly in the midst of Coronavirus. These cartoons specifically comment on the propensity of their politicians to seek medical help abroad instead of using their own services.

The current Covid-19 crisis has extended this satirical social critique beyond just commenting on their own state structures and politicians (although there is certainly no shortage of these cartoons and memes across different African countries). Rather, these humorous critiques have extended to commentary about the global order.

African countries are frequently featured in media for health crises and outbreaks, most recently the Ebola epidemics in West Africa and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Both implicit and explicit narratives framed these epidemics often pointing to ‘backward’ social practices contributing to transmission, making it ‘their own fault’. By contrast, European narratives about Covid transmissions have not been so quick to victim-blame, rather pointing to structural and governmental issues.

During the West African Ebola epidemic too, people were victimised on a global scale. The outbreak led to a mass hysteria in the global North, leading many countries to impose restrictions and, in some cases, full bans from Ebola-affected areas. However, memes, like the one featured below, acted as social commentary during this period, pointing to how disease becomes ‘more prominent’ when it is seen as a problem in the global North.

In the midst of Covid, however, these narratives have been turned on their head. From March onward, many African countries began banning flights from Covid hotspots, including Europe. Indeed, most initial infections found in African countries did come from people who had travelled from European countries.

The irony of the epidemic’s transmission route has certainly not been lost on Africans. Both professional humourists, particularly cartoonists (but also ordinary people) have used the epidemic as a platform for broader colonial critiques. The cartoon below, designed by a Ugandan artist, has circulated across the continent through various social media platforms. It is of course poking fun at European immigration policies, which in recent years, have become more and more stringent. The epidemic, however, placed these restrictions on Europeans, thus creating an undeniable irony and opportunity for humorous social commentary.

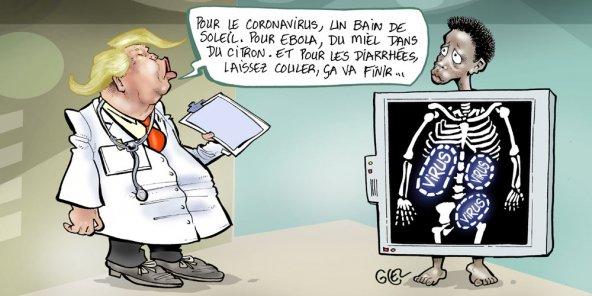

Using an ambiguous joking medium permits people to comment and critique in ways that they may not usually feel comfortable. Covid in particular has allowed ordinary citizens the opportunity to subtly subvert not only their local status quo, but a global one. Humour has been used by Africans to express their Schadenfreude: the misfortune of the mighty, which has provided a form of psychological vindication. When a report leaked that the French Ministry was predicting conflict in Africa as a result of the Covid outbreak, some responded to these reports with satire that reminded the public of the long-troubled relations between France and its former colonies in Africa.

Social media has allowed for these critiques to be widely circulated across continents. Like the disease itself, which can infect anyone (though the economically disadvantaged and minorities are disproportionally affected), humour ignores the boundaries of social distancing. Virtually everyone with access to social media, regardless of status, engages with satire and irony through digital memes and cartoons. Such joking signifies who are able to have a laugh but are simultaneously critiquing the ongoing colonial order that has arguably contributed to the ever-worsening crisis.

‘ ‘For coronavirus, sunbathing. For Ebola, honey and lemon. And for diarrhoea, let it run, that will end it…’

While humour can certainly be used to comment on and even resist colonial structures, there is also a danger in it. Humorous memes and satire can have negative consequences. For instance, they can contribute to the spread of misinformation and fake news in both the global North and global South, as satire can sometimes be misappropriated in an effort to cast blame, resulting in intense social debates and scapegoats.

While satire and social media both have positive and negative consequences, the (post)colonial irony of Covid’s transmission route is noteworthy and African satirists have certainly taken note. Africans are now not only fighting and commenting on the Covid epidemic, but on long-established colonial narratives – and part of this battle is through the medium of humour.