Debating Ideas is a new section that aims to reflect the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series, publishing engaged, often radical, scholarship, original and activist writing from within the African continent and beyond. It will offer debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments.

Typical rural settlement in the Transkei where migrants return.

The 20th century Hungarian economic historian and anthropologist, Karl Polanyi, argued that impersonal, or what he called dis-embedded, economic transactional orders were a unique historical feature of market society, or capitalism. He suggested that, by contrast, the realm of economic transactions in non-market societies was characterised by social and moral considerations, such as reciprocity or redistribution, and not by mere self-interest and maximisation.

Polanyi was mistaken, however, in one important regard. The idea that capitalism or market society is asocial and driven by a universal logic of maximising behaviour is problematic. In consumer society, social values, morals and aspirations mould needs and wants, which in turn shape the transactional orders and production regimes of capitalism.

The most important take-away from Polanyi is, perhaps, that economic behaviour everywhere is determined by both utilitarian and socio-cultural forces. The British social anthropologist Henrietta Moore recognised this when she warned (Marxist) economists not to think simply of the ‘reproduction of labour power’ as a matter of biological reproduction, but to see it as a matter of reproducing socialised people and identities.

It is in times of societal threat, such as during the present crisis caused by the spread of the Covid-19 virus, that social reproduction acquires a special salience as people reconnect with their roots and reflect on their core social identities. This is one of the reasons that governments all over the world have supported people seeking to return to their home countries or homelands to be with their families. In South Africa, there has also been increased movement between urban and rural areas that has caused tension during the stringent lockdown imposed by the national government.

The problem, as the government is realising, is that many South Africans do not have only one home, but relate closely to two or more places. These often include a place in the city and at least one home in the countryside. Indeed, people without a rural home, especially for their children, are often said to lack the means of acquiring an authentic black, South African identity.

In the present context, in which many black South Africans still feel alienated and vulnerable in South African cities, the current hard lockdown imposed by the government is problematic. Who has the right, people ask, to stop them from going home, especially in these trying times?

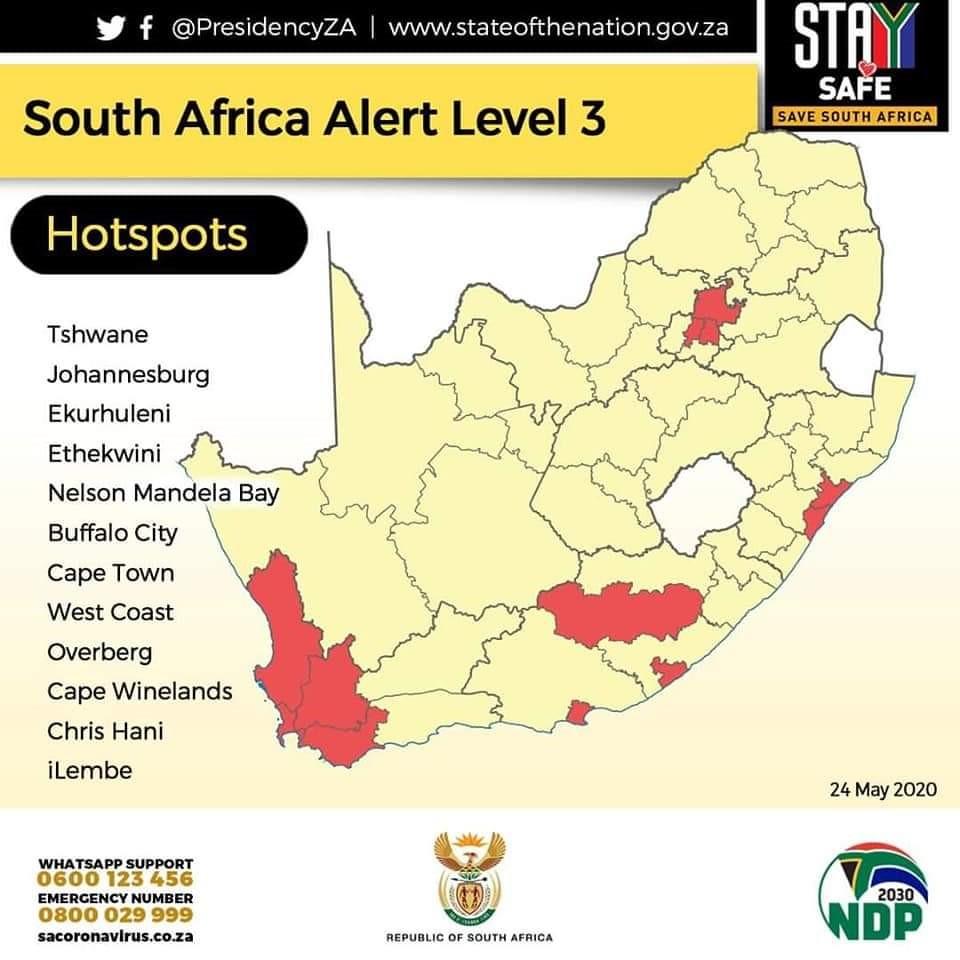

Map of lockdown hotspots in SA.

Accordingly, law enforcement against the grain of translocality and circular migration has resulted in a war of words between regional governments, who are struggling to keep people confined to local cities and regions. The tensions between these authorities reveal there are no institutional structures for the management of translocality and double-rootedness in South Africa.

Migrant labour, translocality and people’s science

Lockdown, like development, has created territorial traps. It appears to be an obvious, seemingly self-evident response to Covid-19 from both biomedical and classical market-economics perspectives. From the biomedical point of view, germs and viruses travel with people; so, stopping people from moving represents a basic method for preventing the disease from spreading. Meanwhile, rational-choice economists assume that population movement is unidirectional as people logically leave areas of low economic opportunity, such as the former rural homelands, for the cities.

By contrast, those who pay close attention to the socio-cultural aspects of economic theory and focus more on what people are doing, the so-called ‘substantivists’ in Polanyi’s framework, would have noticed that many people in the cities are gravitating to the rural areas. The rationalists would say that these people are moving because they realise that jobs will be scarce during the Covid-19 crisis and there is more space for social distancing in rural areas.

However, we might interpret this movement differently. People are more likely to reflect on the social and cultural significance of home at this critical time, especially for people who have essentially never been welcomed and given full citizenship in the city. They may reflect on questions of moral integrity and security; kinship and close-knit social relations; and cultural identity, as well as historical experiences of migration and the threats to life and dignity posed by the spread of Covid-19 and the official responses to the virus.

The evidence from rural communities in the Eastern Cape suggests that many people from the cities have taken advantage of the present opportunity to return to their rural homes, because they want to be with their families at this dangerous time. They are apparently also catching up on customary ceremonies and rites that they might not have been able to perform earlier by virtue of long absences in the city.

Taxis carry migrants.

Visits to the rural home are enabling people to re-centre their lives, spiritually and culturally, and re-connect their families and their children to their home places. In reflecting on this movement, it is important to note that those who have land and homes in rural areas have retained these often at great cost to themselves and their families as a form of resistance to colonialism and dispossession.

Holding on to these places, however remote they may be, has its own rationality. There is a logic to why people continue to ‘suffer for territory’ in the ways they do, and retain their connections with an ancestral home and culture and to ideas of an ‘old nation’ which have been rapidly pushed aside by new ways and social change in recent years.

In this context, home is a kind of heartland, a reference to a moral community. It is not an abstract place defined by Western science, a site for the spread of germs and disease, nor merely a spatial container of economic opportunities. In terms of the ‘people’s science’ of everyday life, home in South Africa is translocal and is often stretched across space to ensure that both survival and social reproduction remain possible in difficult times.

Consequently, economic and medical science will not be effective in managing the spread of Covid-19 in South Africa unless they are able to connect with people’s own practices of householding and adaptations to the challenges of everyday life. Some important insights into the moral, social and economic circuits and regimes of values that have influenced translocality and the perpetuation of migrant labour in South Africa since the end of apartheid are explored in a new collection I co-authored, Migrant Labour after Apartheid: The Inside Story (HSRC Press, 2020). The book tells of the dynamics of internal movement and double-rootedness as a persistent feature of social life in southern Africa.

To comprehend the contemporary dynamics of urbanisation, economic development, and health and welfare provision among the poor in South Africa in this time of Covid-19, it is also important to recall Karl Polanyi’s insights on the social embeddedness of economics and Henrietta Moore’s view on the socio-cultural dynamics of economic reproduction.

Translocal development

Against this background, the apparent failure of the South African government to develop policies and programmes that are responsive and attuned to the promotion of a ‘people’s science’ and the persistent practice of translocality in South Africa lies at the heart of the current contestation among provinces over the movement of people.

The absence of any formal recognition of such movement and the contributions it makes to people’s lives and livelihood struggles makes it difficult for the government to develop mechanisms that are able to manage and direct flows of people and resources across provincial boundaries safely. Hopefully, the issue of translocality and development will receive more serious attention in national and regional development policy in future.

The author’s latest publication can be be found at: https://www.hsrcpress.ac.za/books/migrant-labour-after-apartheid.