You Will Die at Twenty and the Adichie moment that never came

I am beyond ready for stories that could give the lost little Sudanese girl in the US I once was, a template for loving herself.

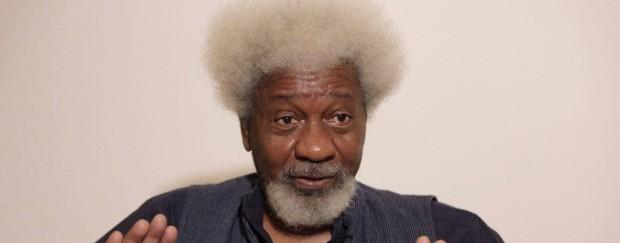

A still from the breakout Sudanese film You Will Die At Twenty.

When I played make-believe as a Sudanese child growing up in the US, the characters in my imagination were always white. I had little reason to believe they could be anything but. I rarely saw Africans in the media, except as sorrowful children holding out their hands in charity commercials that had the same tone as those for injured puppies. The white characters in books and movies – and so my mind’s eye – could go out and have adventures, but the girl in the mirror existed without moorings and could go nowhere.

My family’s summer trips to Sudan were the highlight of my year. Sudan was freedom, marked by long days spent playing outside with my cousins-turned-sisters away from the adult supervision that was omnipresent in the US. Sudan was also stability; my grandfather’s house had been there since my mother was little, so different from the many apartments and houses we moved between in America. But in the rest of my life, there was no vocabulary to describe the large, flat houses filled with rotating casts of “close” relatives whose faces I did not always recognise, but whose love for me was palpable.

When we returned to the US, Sudan was forced to shrink to the size of our house; nobody outside had ever heard of such a country unless they knew about the conflict in Darfur. There was no joy in the Africa we saw depicted in the US; only a vast, unquenchable need. And sure enough, as a teenager, I could not help becoming less content with my Black skin, with the incomprehensible foods on our dinner table, with my unconquerable Otherness.

This began to change when we studied The Thing Around Your Neck by Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in English class. It was thrilling. Africa in English class! Africa rescued from the sad footnotes of Social Studies! That the words of Adichie, an African woman, were being taught in the same classroom where we learned Shakespeare and Fitzgerald meant everything to me. I remember thinking, as I zipped through her short stories, I know those girls, I can see that house. Even though her characters lived on the other side of the continent to the country I knew, I recognised myself and my family on her pages. I realised how absent we had been in everything else around me.

As I sat in the dark, waiting to watch You Will Die at Twenty, last year’s breakout Sudanese film, I felt sure that I was about to have another Adichie moment – except better, because it would be my country and not just my continent represented. Instead, what followed left me devastated.

You Will Die at Twenty tells the story of Muzamil, a young man living in a rural Sudanese village. It is prophesied at birth that he will die aged 20, a prediction that destroys his family. His father flees to look for work abroad, while his mother spends her time counting down the days until he dies. Muzamil’s schoolmates shun him and call him “son of death”. By young adulthood, he is close only to his childhood sweetheart Naima and has passively accepted his fate.

It is only when Suleiman enters the picture that things change. This character, who returns home after leaving long ago, represents the introduction of Western values into the static Sudanese village. Suleiman challenges Muzamil’s faith by involving him in the sale of bootleg alcohol. He introduces him to the outside world through the screening of sexually provocative films. He kickstarts Muzamil’s revolt against superstition.

In contrast to Suleiman, the other villagers do nothing to help. In one scene, Muzamil goes home to find his mother, Sakina, and other women preparing for his funeral. Even the villagers who express doubts about the mother’s superstitions do little to stop her. As such, the whole community is complicit in Muzamil’s misery, the only exception being the Westernised saviour Suleiman.

So much of You Will Die at Twenty rang false to me – not least the village’s decision to side with Sakina. The Sudanese communities I’ve been a part of, in the US and Sudan, take care of each other. Anytime I need something, there is a cousin, a friend, a neighbour willing to provide a place to stay, a ride to the airport, a shoulder to cry on, no questions asked. When my grandfather died, my father’s old school friend drove me several hours home. My father’s cousin flew in to attend my wedding in Sudan last year despite massacres occurring in the neighbouring city weeks before. Where, then, were Muzamil’s cousins? Where were those who, in any Sudanese community I’ve seen, would’ve defended him to the death rather than watch his mother destroy him?

It is clear the film was designed for Western audiences. This was apparent from its message that Africa cannot progress without European guidance to its visual references, such as the continual parallels between Sakina and Christian depictions of the Virgin Mary. My husband, who grew up in Sudan, did not pick up on these allusions because they were meant not for him.

This Western orientation was perhaps unsurprising given that the film was partially funded by French and German production companies. But if it is aimed at Western audiences, it has an even higher responsibility to challenge harmful stereotypes. We live in a world in which the UK prime minister has written that Africa’s problem is “that we [Europeans] are not in charge any more”. We have a US president who thinks African nations are “shithole countries”. Both men believe that Africans have nothing to offer the world and must be saved from themselves.

Fiction can challenge those false narratives. But instead, You Will Die at Twenty went out of its way to reinforce them. But there was no need to do so: Muzamil could have found empowerment through his love for Naima, through the return of his father, or in the Quranic school that was his first escape from his mother. He could learn lessons from Suleiman too, but only in a process through which Suleiman would learn just as much from him.

I have spent most of my life in the US but have found that my true strength lies in the values passed down from my mother – my faith, my loyalty, my belief in the importance of community. These values may be less traditionally Western, but there is nothing in them that is incompatible with Western society. In fact, they are what provide meaning to my daily life here in the US.

My teenage self, who could not help being affected by the media message that everything African was weaker, was terminally unhappy. I spent long nights on my bedroom floor, feeling so trapped in my own body.

It was not until later in college – when I began to make solo trips to Sudan, started to connect to a Muslim community in the US, and no longer felt constrained by my African inheritance – that I became happy. I realised that my Sudaneneseness – like the other parts of identity – is nothing to escape; rather, it is something to embrace, wholly.

Walking out of the theatre after watching You Will Die at Twenty, my husband and I were overflowing with outrage. It felt like being transported back to my childhood when the only narrative I saw about Africa was that it was a problem for which the West was the solution. I am beyond ready for stories free of Western-flavoured saviours. Stories made not just about but for Africans. Stories that could give the lost little girl I once was a template for loving herself.

You Will Die at Twenty is screening at Film Africa which takes place 30th October – 8th November 2020 through both online screenings and physical screenings in London.

You have such a mastery of words. My interest was piqued by the headline and I meant to just skim through but ended up reading everything and loved it. Beautiful narrative.

It is sad that we have taken to telling the stories the world wrote for us, rather than our own true stories.

However, I do feel that this film’s story might not be so bad if it were just one in a sea of a million other more Afro-central narratives, rather than the norm.

This calls for more investment in the Media industry by well to do Africans, in the continent and the diaspora.

Top-notch write up there!

Thank you for teasing out the subtext of this much-touted film. I have often been baffled by the fact that people whose mode of being is rooted in a meaningful sense of community and togetherness look up to people whose mode of being is premised on seeing the other as separate from themselves rather than an extension to themselves as the concept of Ubuntu beautifully embodies. Having been the dominant in an uneven power structure for the last 500 years, the west/America have imposed their alienated and alienating form of life on the rest of the world with the result that dehumanization has become the status quo.

Let me conclude with a quote from Chimamanda that explains why the dominated internalize the stories of the dominant:

“Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person.”

He who pays the piper dictates the tune. The narrativity of all You Will Die At Twenty (be it movies, documentaries and literary works) is as good or otherwise as the dictates or body language of the sponsors. Imagine the narrative if the movie was sponsored by Sudanese arts agency or Zeena

is chloroquine available over the counter https://chloroquineorigin.com/# hydrachloroquine