Can South Africa come to Zimbabwe’s rescue by ending “quiet diplomacy”?

Western diplomats’ holier-than-thou rhetoric is unlikely to help. South Africa can be more understanding, sensitive and practical.

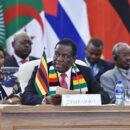

President Cyril Ramaphosa of South African with President Emmerson Mnangagwa of Zimbabwe in 2019. Credit: GCIS.

Zimbabwe’s worsening economic and political crises seem to be never-ending and still getting worse. The misplaced expectations that the “new dispensation” would provide an escape route following the 2017 “coup“, in which President Robert Mugabe was replaced by President Emmerson Mnangagwa, were short-lived. If anything, things have got worse.

It is a nightmarish combination: factional fighting within the ruling party and military top brass; capture of the economy by business-political elites; relentless corruption across public activity; violence by state security forces against dissent; sanctions by the international community; lack of investment; and a divided opposition barely worthy of the name.

And added to all this is the COVID-19 pandemic, now accelerating across the region, with many of Zimbabwe’s elite being struck down, including four cabinet ministers.

Tough times for most

In the midst of long-running political and economic chaos, people in Zimbabwe must now get on with their daily lives during a pandemic. With many having lost formal employment, the economy operates largely informally and public services barely function. Times are tough for most. A “lost generation” is talked about – those growing up since the late-1990s have not seen any of the fruits of independence that people profited from in the 1980s. The image of the educated Zimbabwean, employable across the world, is fast disappearing.

This dire situation has made self-reliance and local innovation essential. And access to land, as a vital route to securing livelihoods, is especially important. This is why the land reform, especially its distribution to many households – who are in turn linked to many more in the communal and urban areas – in the smallholder A1 areas has been so vital to Zimbabwe’s story over the past 20 years. Without state support and shunned by donors as being “contested areas”, the A1 resettlements have for many been the focus for survival in a collapsing economy.

The “development” agencies meanwhile have concentrated on humanitarian and emergency aid. They have avoided the productive sectors of the economy. The aid they have provided is much needed, but it’s barely making a dent on the core challenges of economic development. The state has hardly been present, so incapacitated has it been by the exodus of skilled personnel, lack of funding and rising debt. Instead, it has been people’s hard work and ingenuity that has held things together…but only just.

Those living in the elite neighbourhoods of Harare – the party, business and military elites and the expat, diplomatic and donor community – are shielded from much of the worst. They have foreign exchange cash, health insurances and the ability to escape to South Africa if needs be. The golf courses and some tourist resorts are also still open, and gloriously empty. For most people, though, the situation is really difficult, and increasingly so, as the chasm between the (very few) rich and the (majority) poor increases. As everyone has been saying for over two decades: it can’t go on, surely.

South Africa to the rescue?

So what can be done? For a long time, opposition supporters and allied liberal commentators from inside and outside Zimbabwe were holding out for “regime change”. For many years, Mugabe was the bogey-man, so when a well-oiled PR machine emerged around Mnangagwa, some fell for the spin. Others focused on the opposition and the hope of electoral change, but when Morgan Tsvangirai died and the opposition fell apart in unseemly disputes, this option seemed to shrink. Now hopes seem to be pinned on South African intervention.

An interesting International Crisis Group (ICG) briefing came out recently that suggested the South African government was abandoning its approach of “quiet diplomacy” promoted by former president Thabo Mbeki, premised on solidarity between two liberation movements, and becoming more assertive. This is probably necessary to unblock the impasse. Unlike previous ICG commentaries, this one is more sanguine about the prospects of opposition politics. Endemic corruption and economic mismanagement is evident across the state, mostly at the hands of ZANU-PF politicians, but also from MDC allied politicians in major cities. The solution no longer seems to be a naïve assertion that all will be well with a new party in power; even the once-feted Nelson Chamisa’s star seems to have somewhat faded.

Unravelling “state capture” by political and military elites is not straightforward, as South Africa has clearly found in addressing the catastrophe of the Jacob Zuma era. However, rather than holier-than-thou rhetoric from Western diplomatic missions about “good governance”, maybe President Cyril Ramaphosa and colleagues will be able to address the Zimbabwe situation more sensitively and concretely with practical solutions, rooted in a better understanding of the context.

Pragmatic compromises

So can South Africa engineer some form of national government in Zimbabwe that incorporates opposition politicians, technocrats and others, and sets up forms of accountability that stops the rot? It will not be an easy task, especially in the midst of a pandemic, but it will be necessary to satisfy international investors and aid donors. And it may be the only survival route for some within ZANU-PF. Backing a more technocratic political network within and outside the ruling party may provide the basis for a relaxing of sanctions too.

The South Africans will have to seek a pragmatic solution that is widely acceptable. Maybe such an initiative might just capture the moment when there is a new administration in the US, and find a way for the UK and EU to find a route through the sanctions impasse. Easing sanctions could have a huge impact. For example, sustained development in the land reform areas has been constrained for two decades due to their designation as “contested areas” by Western donors. The agreed compensation deal with former white farmers offers a (yes tricky and fraught) way forward, and the potential for investment and growth from the core sector of the economy – agriculture – opening up.

Of course there must be conditions to any deal, with political reforms firmly on the table. What this means for scheduled elections in 2023, for the military’s support to a new government and for some of the most corrupt in the political-business elite who profit from ongoing chaos, is unsure of course. As Brian Raftopolous argues, “Zimbabwe’s future looks bleak. Its state continues an authoritarian trajectory as it carries out its intention to dismantle the opposition. Yet the legacies and the futures of Southern Africa’s liberation movements face increasing public scrutiny even as the alternatives remain opaque.”

South Africa cannot afford the complete collapse of Zimbabwe given the fragility of its own economy. And with insurgency troubling Mozambique, the usually stable southern African region looks extremely volatile, requiring solutions soon.

This post and first appeared on Zimbabweland.

A better question is: Could South Africa become the next Zimbabwe?