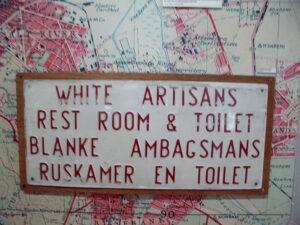

How does one write the history of people thought not to exist? In apartheid South Africa, the obsession to maintain political and economic power for the white minority at the expense and exploitation of the black majority spawned a society in which skin colour determined every aspect of life. Top jobs and educational opportunities were reserved for whites; Africans’ freedom of movement was restricted, they were barred from owning land, organizing in the workplace or mobilizing politically. Other “racial groups” – so-called coloureds and those of Indian descent – suffered fewer restrictions but were similarly consigned to second-class citizenship.

Despite the ubiquity of race, these groups were not as monolithic as they appear. Historians have long recognized this – except when it comes to the main beneficiaries of apartheid. Popular understandings of colonialism and apartheid imagine whites as homogenously wealthy and powerful, perpetually waited on by scores of black servants. While historians recognize that many whites (an average of 40%) remained in blue-collar jobs throughout the apartheid era, they nevertheless argue that this did not make them workers, but rather labour aristocrats aligned with the ruling bourgeoisie in benefiting from the exploitation of the black majority. Meanwhile, the apartheid state’s ethnic and race-based politics by definition pushed an image of whites as classless. All of these views have led to an absence of attention to class in the white population, and the impression that white workers did not exist.

My book Privileged Precariat: White Workers and South Africa’s long transition to majority rule challenges this view. It focuses on the experience of the white industrial workforce and their unique social position in apartheid-era South Africa. Through race-based discriminatory legislation, lower-skilled white workers were shielded from black labour competition and received inflated wages in exchange for their political support for the regime. Thus, their class-based vulnerability was effectively concealed by their race-based status.

Autor’s book from IAI

I was particularly interested in how these workers responded when the labour legislation which protected their privileged position was dismantled. This occurred long before the formal end of apartheid in 1994. Starting from the 1970s, I show how labour reforms saw the apartheid state withdraw its support for working-class whiteness. This sent white workers searching for new ways to safeguard their interests in a rapidly changing world. Focusing on the blue-collar Mineworkers’ Union (MWU), my book tracks how this organization expanded its membership to represent blue-collar whites across a range of industries and aligned with right-wing groups to resist democratization. However, South Africa’s transition to majority rule in 1994 proved the futility of this strategy. The MWU then changed tack again, shedding its working-class identity to reposition as a civil society organization. By the new millennium, it had become the Solidarity Movement, a social movement appealing to cultural nationalism and expressing state-like ambitions.

In contemporary South Africa, the Movement and its subsidiary organizations – most prominently, AfriForum – is increasing its prominence and appeal. It claims to represent the interests of minorities in the context of “black majority domination”, and to speak for white Afrikaans-speakers in particular. While mobilizing outside formal party politics, it is a vocal critic of the black majority-ruled state and pursues the creation of institutional, community and even virtual spaces for “self-determination”. Once more, South African society is being cast in terms of racial and ethnic groups, and Afrikaners are presented as a culturally and politically united people – a classless volk.

My analysis places the long transition experienced by white workers since the 1970s, and how this has shaped contemporary South African politics, in the global context of the ascendance of neoliberalism and identity politics. I ask how the recent articulations and strategies of the Solidarity Movement reflect and inflect the national populism, anti-multiculturalism and anti-globalization politics which have, in recent years, trained attention on white working-class voters in the Global North. While in that context workers are part of a racial majority, they are said to have been “left behind” politically, economically and culturally since the 1970s, and political shifts to the right are understood as a “working-class backlash”.

My book demonstrates how in South Africa, white workers didn’t only exist but remain a political force – albeit in a different form than during much of the twentieth century. Class divisions clearly played an enduring role in shaping white society and politics. Moreover, by bringing together local and global dimensions, this research breaks away from the parochialism which often characterizes scholarship on South Africa. Offering insights from the Global South and the strategies of the white minority, it contributes to an understanding of how class shapes racial identity and politics in the era of neoliberalism.

Race-based workplace segregation

[…] Source link […]

[…] Source link : https://africanarguments.org/2021/08/how-class-colors-race-south-africas-white-workers… Author : Danelle van Zyl-Hermann Publish date : 2021-08-18 07:17:51 Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source. Tags: AfricasclassColorscontextGlobalraceSouthWhiteworkers ADVERTISEMENT Previous Post […]

Best view i have ever seen !