Sudan’s self-coup and four factors that will determine what comes next

The Sudanese masses brought down governments in 1964, 1985 and 2019. They could present another stern test to the military.

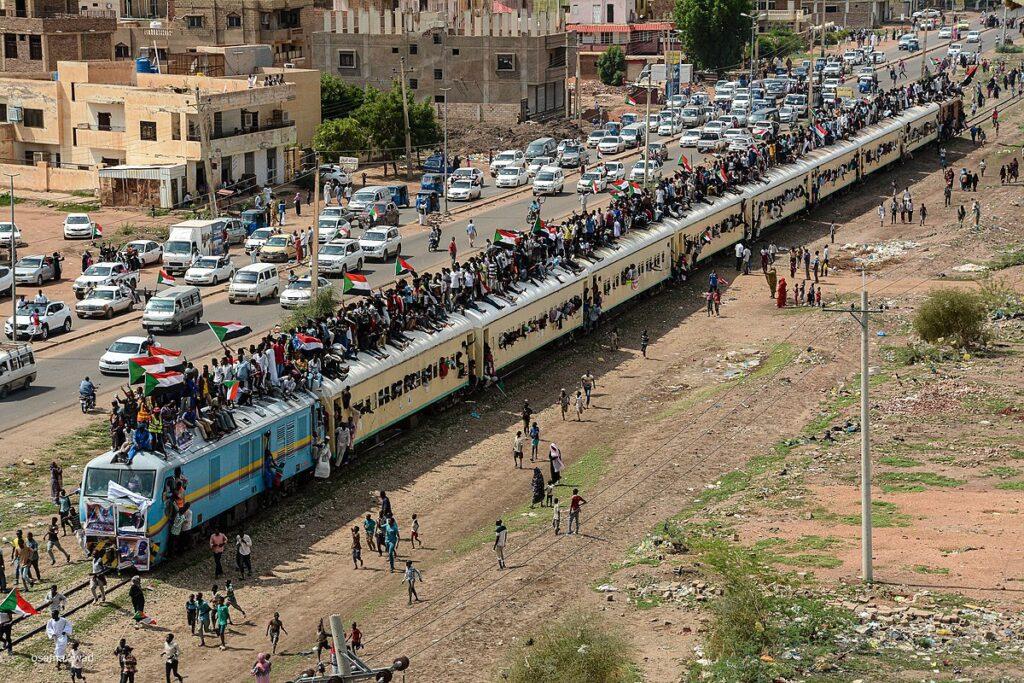

Protesters in Sudan’s 2019 Revolution. Credit: Osama Elfaki.

This week the head of Sudan’s Sovereign Council, General Abdel Fattah El Burhan, declared the dissolution of the transitional council, which has been in place since the overthrow of former president Omar el-Bashir in 2019. He also disbanded all the structures that had been set up as part of the transitional roadmap, and decreed a state of emergency.

In essence, he staged a palace coup against the transitional authority he chaired.

The general’s actions, which included the arrest of Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, are a culmination of a long period of tension between the civilian and military wings of the council. The tensions were punctuated by an alleged attempted coup only weeks earlier. The days leading to the palace coup were marked by street protests for and against the military.

Does this mark the end of the transition as envisaged by the protest movement?

The popular uprising against Bashir’s government was led by the Sudan Professional Association. It ushered in the political transitional union of civilians and the military establishment. The interim arrangement was to lead to a return to civilian rule. But this cohabitation was tenuous from the start, given the oversized role of the military in the transition. Moreover, the military appeared to be reluctant to see the civilian leadership as an equal partner in shepherding through the transition.

Nevertheless, until recently there had been progress towards creating the institutional architecture for the transition. Despite the challenges and notable tension between the signatories to the accord, it was never evident that the dysfunction was so great as to herald the collapse of the transitional authority.

For now, the transition might be disrupted and in fact temporarily upended. But the lesson from Sudan is never to count the masses out of the equation. Their ability to mobilise and confront counter revolutionary forces cannot be underestimated.

Unfinished business

The transitional pact itself had been anchored by eight arduously negotiated protocols. These included regional autonomy, integration of the national army, revenue sharing and repatriation of internal refugees. There was also an agreement to share out positions in national political institutions, such as the legislative and executive branch.

Progress towards these goals was at different stages of implementation. More substantive progress was expected to follow after the end of the transition. This was due in 2022 when the chair of the sovereignty council handed over to a civilian leader. This military intervention is clearly self-serving and an opportunistic power grab.

In November, the rotational chairmanship of the transitional council was to be passed from the military to the civilian wing of the council. That meant the military would cede strong leverage to the civilians. Instead, with the coup afoot, Burhan has announced both a dissolution of the council as well as the dismissal of provincial governors. He has unilaterally promised return to civilian rule in July 2023 through national elections.

Prior to this, the military had been systematically challenging the pre-eminence of the civilian authority. It undermined them and publicly berated them for governmental failures and weaknesses. For the last few months there has been a deliberate attempt to sharply criticise the civilian council as riddled with divisions, incompetent and undermining state stability.

Since the revolution against Bashir’s government, the military have fancied themselves as generals in suits. They have continued to wield enough power to almost run a parallel government in tension with the prime minister. This was evident when the military continued to have the say on security and foreign affairs.

For their part, civilian officials concentrated on rejuvenating the economy and mobilising international support for the transitional council.

This didn’t stop the military from accusing the civilian leadership of failing to resuscitate the country’s ailing economy. True, the economy has continued to struggle from high inflation, low industrial output and dwindling foreign direct investment. As in all economies, conditions have been exacerbated by the effects of COVID-19.

Sudan’s weakened economy is, however, not sufficient reason for the military intervention. Clearly this is merely an excuse.

What next?

The success or failure of this coup will rest on a number of factors.

First is the ability of the military to use force. This includes potential violent confrontation with the counter-coup forces. This will dictate the capacity of the military to change the terms of the transition.

Second is whether the military can harness popular public support in the same way that the Guinean or Egyptian militaries did. This appears to be a tall order, given that popular support appears to be far less forthcoming.

Third, the ability of the Sudanese masses to mobilise against military authorities cannot be overlooked. Massive nationwide street protests and defiance campaigns underpinned by underground organisational capabilities brought down governments in 1964, 1985 and 2019. They could once again present a stern test to the military.

Finally, the international community’s appetite for military coups is wearing thin. The ability of the military to overcome pressure from regional and international actors to return to the status quo could be decisive, given the international support needed to prop up the crippled economy.

The Sudanese population may have been growing frustrated with its civilian authority’s ability to deliver on the demands of the revolution. But it is also true that another coup to reinstate military rule is not something the protesters believe would address the challenges they were facing.

Sudan has needed and will require compromise and principled political goodwill to realise a difficult transition. This will entail setbacks but undoubtedly military intervention in whatever guise is monumentally counterproductive to the aspirations of the protest movement.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.