Debating Ideas is a new section that aims to reflect the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series, publishing engaged, often radical, scholarship, original and activist writing from within the African continent and beyond. It will offer debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments books.

Gibreil Ibrahim’s tweet

The coup in Sudan on 25 October shut down the internet and therefore most social media. One of the first tweets to wriggle its way out of the shutdown was from Gibreil Ibrahim, a former rebel leader who became the finance minister in February. He was appointed in a reshuffle that gave former rebels senior cabinet positions, a few months after they signed the Juba Peace Agreement. The peace agreement was also signed by Sudan’s transitional government which emerged from the collapse of the regime of former president, Omar al-Bashir. It was an uneasy coalition of military commanders who had risen up the ranks under Bashir, and technocrats backed by the street protestors who had deposed him. For many reasons, the ruling coalition became more fragile after Gibreil and the other rebels joined. In October, the security men arrested most of the civilian cabinet and declared themselves in charge.

Gibreil wasn’t arrested, and his 30 October tweet gave the impression that he could see both sides of the argument. As protestors surged towards the cops and snipers, he told the social media world:

‘’The Sudanese people have the right to express their opinions by all peaceful means. But wrecking pavements and electricity poles is destruction of public property, brought by the citizen’s sweat, and it’s nothing to do with peaceful expression.’’

Just before the coup, Gibreil and another former Darfurian rebel, Mini Arko Minawi, formed a breakaway faction of the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC), the coalition that helped lead the 2019 protests against Bashir. In October 2021, protestors from the breakaway FFC faction joined a Khartoum sit-in calling for the restoration of military rule. On 25 October, the military arrested FFC cabinet ministers and the next day unlawfully suspended the constitution.

Once again, the government of Sudan was withering into the shape of its security organs. But this time, the security organs were backed by leaders of peripheral militias who had long fought them.

Gibreil Ibrahim became the chair of the Darfur-based rebel Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) ten years ago, after the government killed his brother Khalil, the founder of JEM, with a precision airstrike. Khalil was the most politically experienced of Darfur’s rebel leaders: he grew up in the Islamist movement and its party militia, and retained an enigmatic link with dissident Islamists until the end. But his rural militia had a narrow ethnic base, in his own Zaghawa ethnic-linguistic community. JEM and nearly all the other Darfur rebel militias were militarily defeated in a counter-insurgency campaign launched in 2014 by a government-aligned rural militia, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). For the next five years, JEM bided its time with sullen unilateral ceasefires, “for humanitarian purposes”.

The 2014 counter-insurgency campaign, Decisive Summer, left Sudan’s rebellious peripheries in the dead-end of humanitarian ceasefires, and propelled Hemedti, the RSF commander, into government. When Bashir was deposed by urban protests in 2019, Hemedti became Sudan’s youngest vice-president. His forces played a key role in the 25 October coup d’état. Sudan’s military can no longer organize a coup without them.

The creatures of the deposed

Many Sudanese people refer to deposed former president Omar al-Bashir as “the deposed” – a snarky shorthand which stresses the indignity of his ousting rather than his long contribution to Sudanese politics. His thirty-year presidency reshaped Sudan, sweeping away old political formations and old patterns of accumulation, and replacing them with a political–economic–security complex outsourced to his Islamist movement. His wars split the country into two – but in the process gave the country a decade-long oil boom, which temporarily made Sudan a middle-income country.

Not much of this lasted. But Bashir had one durable, exportable, achievement: the rural militia. These militias fought for control of the muddy pastureland that held the country’s oil wealth, or the dusty savannahs and deserts where the gold was, and cheaply and efficiently delivered Sudan’s subterranean resources to global markets. When the oil ran out, and Sudan went back to earning most of its foreign exchange from crops and livestock, the most successful militias organized harvest patrols, bought out the Animal Resources Bank and established in 2017 their own Al-Khaleej Bank in partnership with Emirati capital. And now, they have taken control of the Sudanese state.

Militarization of countryside production is not restricted to war-ravaged regions of Sudan but is now an intimate feature of rural life. The tranquil Kordofanian hamlet and the sleepy Gezira village of yesteryear have become sites of military deployment. A special security force involving the RSF has been set up to oversee the harvest season, a time when armed bands roam the land to capture freshly harvested crops still waiting in the fields to be adequately stored and transported. Even more pervasive is the militarization of pastoral livelihoods. One driving factor for the emergence of the rural militia was the expanding commodification of pastoralism and the need to safeguard the treks of herds to export markets in Libya and Egypt. The leader of the RSF, Sudan’s most successful militia, began his career as a livestock trader who worked the hazardous desert routes between northern Sudan and southern Libya.

The emergence of the RSF as a dominant militia with superior numbers of fighters, gun-mounted pick-ups, and weapons has brought with it some measure of stability, especially in regions of southern and eastern Darfur that were ravaged by wars between pastoral peoples over land. Smaller militias and fighting bands were absorbed into the RSF en toto with their command structures intact. Indeed, in Sudan’s vast peripheries the RSF, thanks to its military organization, logistical capabilities and command over surplus, has assumed social provision and insurance functions. RSF units dig wells, organize health care, deliver vaccines and supervise rural extension and the development of entrepreneurship skills à la International Monetary Fund and World Bank recipes. As an employer, the RSF absorbs unskilled labour power on a permanent and a seasonal basis and provides an outlet for the export of labour in the form of fighters to the kings and princes of the Arab peninsula. Combat deployment in Yemen for teenagers from the villages of Kordofan and Darfur or informal labour reserves of Khartoum is one avenue for these youngsters to save cash, bring their mothers to the shanties around Khartoum and maybe build a home or buy a small bus.

The militia form

Rural militias existed before Bashir – back then, they were auxiliaries for the cash-strapped military, or dirty-war shock troops. But Bashir gradually outsourced state functions to these militias. The militia form, which he can plausibly claim as his invention, has gone on to become the key technique of rural governance and resource extraction in the neoliberal chaos zone that stretches from Afghanistan to the Congo. We all depend on them: they bring us coltan for phones, petroleum for transport, drugs for parties, and diamonds for those extra-special moments. Bashir came to power in 1989, during a long economic crisis which left Sudan unable to finance its imports. He was an early adopter of neoliberal governance techniques – austerity, outsourcing and sell-offs of public wealth. In the cities, he repressed resistance with his secret police, and in rural Sudan, he set up rural militias, often by militarizing the leaderships of ethnic communities.

Rural resistance mirrored rural repression: communities at odds with the state set up rural militias, often using ethnicity or tribe as a recruiting sergeant. These militias were all but defeated by Hemedti’s 2014–16 counter-insurgency, but they were not supplanted by alternative, more inclusive models of rural governance. The rural militias stayed on as the representatives of the defeated peripheries. When the 2019 revolution came along, many of these rural militia leaders weren’t sure what to do. Instead of seizing the joyous revolutionary moment, they spent over a year negotiating with the transitional civil-military government, eyeing up the strengths and weaknesses of the civilians and the soldiers. Over the course of a long hot summer, Mini Minawi and Gibreil Ibrahim placed their bets on the soldiers.

Consumption and austerity: Bashir’s balance of payments

The summer was long and hot because the government was unable to finance its import bill. Bashir bequeathed Sudan’s urban middle classes an expensive consumption culture, and kept them fed on imported wheat. But he really only had one source of foreign currency: the productive efforts of Sudan’s rural population. About half of export earnings came from crops, forest goods and livestock, and the other half from gold and oil – all from rural Sudan.

Rural Sudan could never produce enough to cover the import bill and Bashir fixed exchange rates and printed money to try to deal with the problem. The resulting inflation brought him down, and the transitional government decided to try and break the cycle of inflation by sharply devaluing the currency – which led to an immediate increase in the price of imports. Gibreil was at the finance ministry and he tried to soothe the pain with salary hikes, cash transfers and new investments in social services. But inflation went out of control – over 400 per cent in July, three times as high as Lebanon’s inflation, eight times as high as Yemen’s.

Bashir’s long wars turned the military and the rural militias into something as big as the state. The Military Balance, an annual publication guesstimating the size of the world’s militaries, gives a sense of the scale of military expansion during the Bashir years (these figures do not include thousands of rebel militia soldiers).

Source: The Military Balance

This graph could also be titled “The true cost of austerity”. Sudan needed rural militias to keep up its systems of consumption and production. The October 2021 coup shows how deeply embedded this system is. It has produced the army, the RSF and the former rebels in the cabinet, and used their violence to span the huge divides between rural and urban Sudan. By militarizing control of rural wealth extraction, it has given commanders a stake in the system. When the military decided on a coup, it sought the support of these rural militias, as a counterweight to the civilians of the FFC, whose support is largely based in urban Sudan.

The challenges faced by the civilian cabinet

The coup also shows the scale of the challenge faced by the civilians in the government. The civilians in the cabinet drew much of their legitimacy from the mostly young, mostly urban protestors who, at great personal cost, led the 2019 revolution which deposed Bashir. Sudan’s militia system works by setting the interests of rural and urban people in contradiction: the services economy which dominates the towns earns almost nothing in foreign exchange, and urban consumption thus depends on the productive efforts of rural primary producers. A key task of any Sudanese ruler is to organize food insecurity so that it falls hardest on rural people, and keeps urban people fed – because urban people present a greater threat to his power. Bashir’s last mistake was to break this rule: by the end of his incumbency, he was no longer able to manage the costs of his militia system and the costs of the wheat imports, and hunger, spread to the cities.

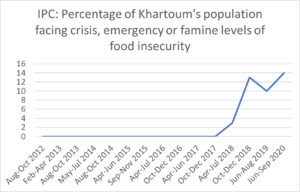

Source: ADD

The 2019 transitional government was based on a compromise between these protestors and Bashir’s security system. One of the main concerns of the security men was to protect their payrolls, their banks and their control over exports. That meant that the transitional government had to come up with the foreign exchange needed for imports while continuing to channel the productive resources of the country towards the vast subsidy paid to the creatures of the deposed. The civilians had to square a circle which Bashir’s ruthless cunning could not square. The main alternative open to the civilians was to leverage international support: the protestors had won widespread admiration for deposing a president backed by Sudan’s world-class militia system. Donors and multilateral financial institutions insisted on macro-economic reforms. Bashir’s government had huge, inherited and un-serviced debts and imports cost twice as much as exports earned. It could not attract enough foreign currency to the country to finance imports and to back the Sudanese pound. Bashir had printed money to finance his spending in Sudan, pushing inflation up. He imported fuel and wheat (Sudan’s urban staple) and subsidized their prices through discounted exchange rates and direct payments to mills and bakeries. Sudanese merchants, often linked to the security forces, clustered around the cheap dollars that circulated around fuel and wheat. The donors were not prepared to support a subsidy system that channelled money to military merchants, even though fuel and food subsidies and the complicated currency arrangements behind them limited pressures on household incomes.

The donors, however, did subscribe to the iron law that only well-fed countries are allowed to subsidize food, and in 2020, the civilian government got rid of fuel subsidies and severely reduced wheat subsidies. In 2021, Gibreil Ibrahim floated the Sudanese pound. Terrifying inflation ensued – by midsummer, Sudan’s inflation rate was three times as high as Lebanon’s, perhaps ten times as high as Yemen’s. An estimated 21 million people were projected to face crisis levels of food insecurity. The government promised a temporary programme of cash transfers, worth 5 US dollars per person per month, to help households cope. But unlike food subsidies, cash transfers require a complicated targeting apparatus and bureaucratic capacity across vast territories that in Sudan are largely controlled by militias – the cash transfer system has reached only a million households in 12 states, and many households have so far only received one payment.

The coup is expected to cut off access to the financial flows from the global North which economic reforms were meant to ensure. The military will need to find dictator-friendly sources of capital which Bashir himself could not find when he needed to save his skin. And any reversal of the coup may require a reassessment of the reforms, which generated a kind of consensus across the transitional government. Gibreil Ibrahim declared they would improve competitiveness. Abdul Fattah al-Burhan, the coup leader, praised them in his first press conference after the October 2021 coup. For the civilian leadership, which brokered Sudan’s new relationship with creditors, donors and international financial institutions, the reforms made them indispensable to the transitional government – without them, Sudan cannot access the foreign currency which is needed to manage a floating currency. But although the civilian leadership supported the reforms, they also have the most to lose from them. The reforms recklessly immiserated millions of Sudanese families, and have deeply stressed the vital relationship between the civilian cabinet members and the source of their legitimacy – the protestors who led the 2019 revolution, many of them organized into local resistance committees which had their origins in the urban protests against subsidy-removal in 2012–14, when Sudan lost most of its oil revenues and faced another food crisis.

Revolutionary energies

Nonetheless, when al-Burhan jailed the civilian leadership, the resistance committees did not blink. They went straight to the streets to confront the snipers with strikes and civil disobedience, brimful of the self-confidence they gained from their decisive role in the 2019 revolution. What lessons should they heed at this terrifying moment?

Three years after the October revolution of 1964 – when urban protestors brought down Sudan’s first postcolonial dictatorship, Abd al-Khaliq Mahjoub, Sudan’s prominent Marxist intellectual, argued that the revolution could only succeed if it democratized rural Sudan. Back then, the revolution was defeated by the two big patricians in Sudan, who were allied to the mercantile interests which skimmed the rural surplus, and who could use their religious prestige to mobilize rural support and crowd out the intellectuals and the trade unions who led the revolution. The formula for rural democratization eluded him – he used the term “popular democracy” as a placeholder for a future he could not yet see.

The resistance committees are in a similar position today. They need to align their politics with rural politics, bent out of shape by the militia system. They may not yet see the future, but they have developed a new revolutionary praxis: the neighbourhood resistance committee as a unit of mobilization, logistics, manoeuvring and political education in urban confrontations with the security apparatus. The committees are today at the forefront of opposition to al-Burhan’s coup.

So far, the committees have efficiently turned political energies into mass action. Thousands of young women and men have been drawn into political struggle through this open-access horizontally-structured organization. The committee provided spaces for new solidarities between urban constituencies fractured by an authoritarian market regime: debate-savvy university students from the salaried middle classes, day-labourers scavenging livelihoods from odd jobs, impoverished industrial workers, unemployed graduates, brick layers, construction workers, artisans, petty traders and peddlers.

The committees have helped Khartoum’s street sweepers and garbage collectors, hired on short term contracts by a state-owned firm, to organize strikes in December 2020 and June 2021, demanding permanent contracts and incorporation into the official government pay scale. Khartoum and Omdurman peddlers organized protest marches in July and August 2021 against eviction orders by the state authorities. A resistance committee emerged among the hawkers of al-Suq al-Arabi, the market area of central Khartoum. One of its leading members explained to the media in October that their ranks included poor students and graduates who had no other means to get by. These achievements show that the resistance committee is a form that can adapt itself to the informal urban economy.

This revolutionary mass proved inexhaustible, un-bribable and undefeatable despite the blunt and bloody terror it faced in September 2013, faced again in the 2018–19 protests which deposed Bashir, and faced once more in the 3 June 2019 massacre, when the RSF shot and raped scores, perhaps hundreds, of protestors. The revolutionary mass accepted the compromises needed to form the 2019 transitional government, and despite the demoralization brought about by divisions in the FFC, and the enormous costs of economic reform, this mass still found the energy for confrontations with the security apparatus after the October 2021 coup.

The wild success of the committees is evidenced by their reproduction across small town Sudan and beyond. During the height of the 2018/19 protests, young women and men from unheard-of villages in Gezira and Kordofan registered their names on the national map through the declaration of their own home-grown committees. For example, in Um Dam Haj Ahmed, north-east of Kordofan’s Bara, the resistance committee used the revolutionary moment to negotiate with the telecoms giant Sudani to pay rent on land appropriated for a telecoms mast to a local youth and sports club.

In Gezira, Sudan’s central agricultural zone, the formula of the resistance committee provided new organizational capacities for generations of landless agricultural workers in labour settlements known as kanabi (a plural form derived from the English camp) that encircle Gezira’s villages. For the inhabitants of the kanabi, citizenship in the promised “new” Sudan is premised on the primary demand of securing land rights amongst anxious landowners. Resistance committees budded and sprouted in the most unlikely of places, in the plantations of the seasonal Gash river in Kassala, a capitalist agricultural venture that dates back to the 1870s, and in al-Zariba, a centre of Sufi learning and patriarchal mores in Kordofan. Deep in Darfur’s Jebel Marra in Nertiti, resistance committee activists organized a weeks long protest camp in July 2020 demanding a ban on weapons and the protection of their farms and livestock from raiding bands. Twentieth-century urban protestors tried several ways to connect with rural Sudan: there was a short-lived Maoist movement in Kordofan, which sought to draw peasants into a struggle dominated by urban proletarians. Delegations of eager young urban students visited peripheral villages and towns. The victory of the revolution, paraphrasing Abd al-Khaliq Mahjoub, might well depend on the ability of the resistance committee to weave together these multifaceted urban and rural struggles, and become a democratic spearhead in militia-governed rural Sudan.

Today’s revolutionaries might not know exactly what they are creating with the agency of the resistance committees. Bashir probably did not fully realize what he was creating as he set up the rural neoliberal militia with operational power extending from the battle zones of Darfur across the Red Sea to Yemen. In the meantime, it is worthwhile to contemplate the humbling resonance of the sacrifices of teenagers on the streets of Khartoum or in far off Nertiti as they face up to the might of a vengeful coercive apparatus now plugged into a security order that binds Abu Dhabi, Cairo, Tel Aviv, Riyadh and Washington. They might not have much to lose, but we and the world might lose them.