Debating Ideas is a new section that aims to reflect the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series, publishing engaged, often radical, scholarship, original and activist writing from within the African continent and beyond. It will offer debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments books.

Every year, on 21 Hidar in the Ethiopian calendar, or 30 November, more than 100,000 people come to Axum from all over Ethiopia to commemorate the founding of St. Mariam Tsion church, with many pilgrims coming on foot, having walked for up to a month.

The infamous 2018 peace accord between Ethiopia and Eritrea was hailed by the international community for shattering the 20-year-old stalemate between the two countries. The rapprochement was presented as an embodiment of African solutions, an “anti-liberal” peace concocted by outward looking heads of state who internally settled the limitations of international mediation and peacebuilding.

I argue here that the international community’s accolade amounted to the endorsement of a liberal text embedding the same monolithic peacebuilding formula of the 2000 Algiers Peace Agreement, which associates and perpetuates violence with political action. I further argue that peace between Ethiopia and Eritrea was never institutionalized, due to the technocratic approach of peacebuilding which sidelines everyday acts of peace and active grassroots peacebuilding exhibited by inhabitants straddled in the borderland region. Liberal scripts dilute political realities and normalize violence which is currently unfolding in the Ethio-Tigray war.

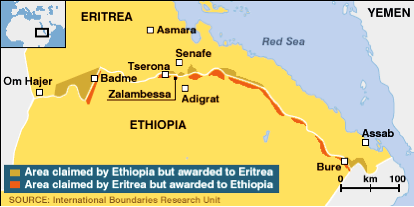

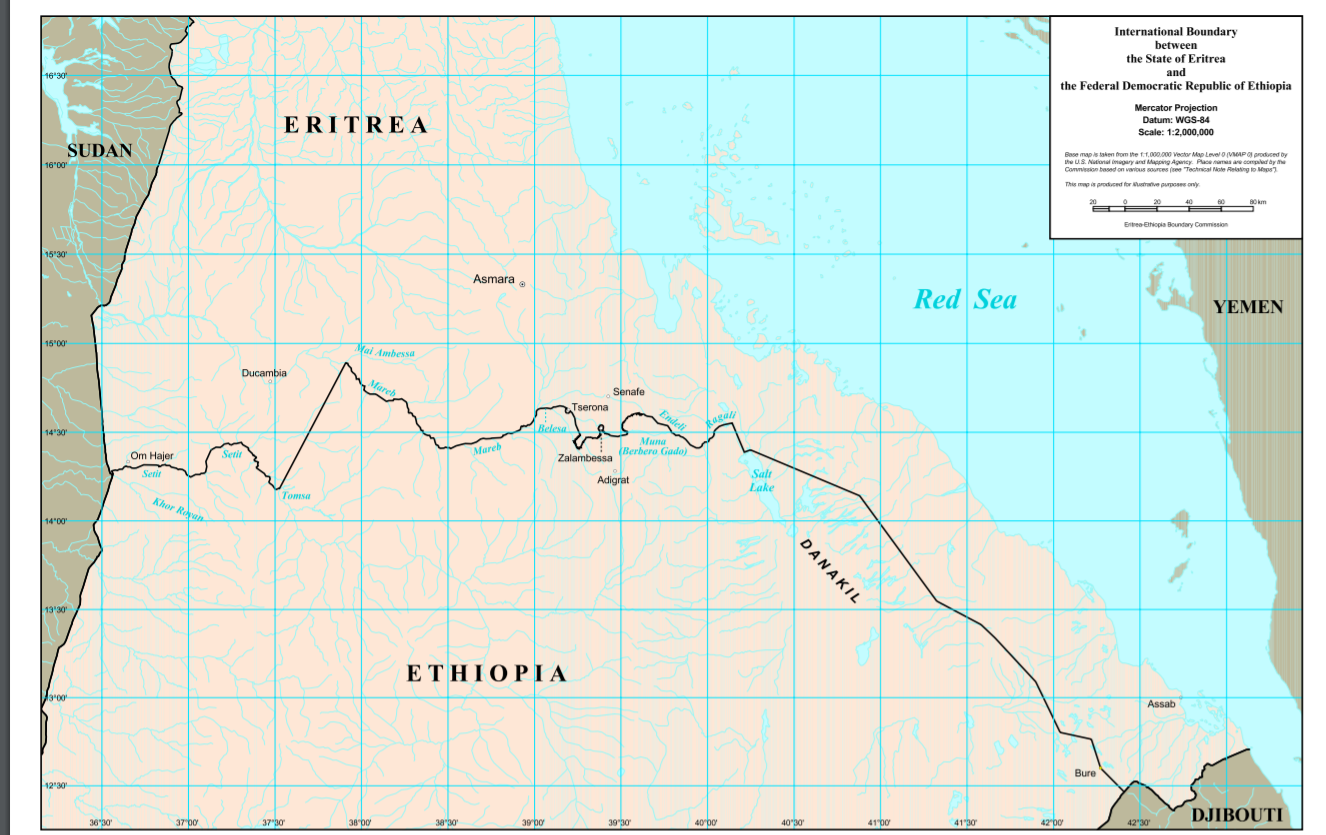

The signing and Peace and Friendship Agreement signalled a willingness to commence political, economic, social, cultural and security cooperation. Most importantly, Ethiopia announced the unconditional acceptance of the Algiers agreement, a ceasefire deal which positioned the UN system firmly at the epicentre of the conflict management environment, and the complete implementation of the contested 2000 border ruling by the Ethiopia-Eritrea Boundary Commission (EEBC). The ruling was the peace industry’s primary tool to resolve the (1998–2000) deadly Ethiopia and Eritrea military engagement, through a formal court system and an arbitration decision by the EEBC for the delineation and demarcations of a previously porous border, using colonial maps and satellite imagery. A UN Mission to Ethiopia and Eritrea (UNMEE) peacekeeping mission was also established to monitor the implementation of the agreement, deploy forces to agreed upon positions and manage the 1000 km-long border and 25 km-wide Temporary Security Zone (TSZ). At the time, international arbitration and adjunctions were regarded as a hermetic approach which dilute the underlying political intricacies of border disputes, but ensure political/legal cover if and when rulings are contested. The ruling contributed to silencing the guns, however, the end of war is not actual peace. Especially for the communities inhabiting the borderland, it meant the abstraction of their daily lives due to a cold war which lasted for more than 20 years.

Sociologist Redie Bereketeab lauded the “maturity of underpinning conditions” within Ethiopia as a breeding ground for peace. The 2018 popular uprising against the TPLF-EPRDF, which dominated the political economy of the country for over two decades, led to the reshuffling of the ruling party’s leadership and provoked the appointment of the 42-year-old reformist leader Abiy Ahmed. Consequently, sweeping reforms were passed: the state of emergency was lifted, thousands of political prisoners were released, the terrorism act revoked, and amnesty was granted to political dissidents. The abstract neatness of the unfolding politics seemed founded on democratic values, good governance, and fundamental human rights of all individuals.

Most importantly, accepting to implement the UN-backed Algiers agreement is endorsing the monolith of international peacebuilding which entailed the establishment of external organs, a boundary commission and a claims commission, to investigate the inception of the conflict, delineate and demarcate a border purview of political settlement. Ultimately, the decisions of the claims and boundary commissions were never realized due to the award of the symbolic town of Badme to Eritrea, bitterly contested by Ethiopia who highlighted challenges that would confront its actual demarcation on the ground. Additionally, the agreement did not grant opportunity for appeals against the final decision and mistakes, provoked during the delimitation process through the use of colonial maps on identifying the confluence of key rivers to mark the border, were never corrected.

In the eyes of the international community, peace was unequivocally linked with the flurry of diplomatic interventions which produced the Algiers agreement, preceded by the efforts of the OAU, which adopted a peace agreement supported by the UN, EU and US, that failed to prevent the escalation of hostilities or secure a ceasefire. Nevertheless, the conceited premise prevailed, the mirage of peace birthed by diplomatic interventions was halted when countries refused to implement the EEBC ruling and reinstated when politics matured enough to endorse the liberal process of peacebuilding. In fact, when peace deals miss the mark, fault is associated with fragile states at the brink of failure lacking state institutions ordained with the task of implementing peace. One-size-fits-all liberal peace processes, which aim to quantify peace and bestow them to warring parties, are extended to link neoliberal economic and political ambitions, amenable to the standards of capitalist economies of the global North. Conversely, the violence harboured by the 2018 Ethio-Eritrea peace deal echoed in the lives of those straddled in the borderland, whose lived realities were discounted from the peace process.

Furthermore, the existence of the Irob, an indigenous community inhabiting the Ethiopia-Eritrea borderland, who strictly identified as Ethiopians, would be endangered due to the EEBC’s delineation of the border, which splits the tiny community between two sovereign states. Equally, the Irob and other communities in the borderlands would have everything to gain from the normalization of relations between the two countries and the re-opening of the border. They would be able to finally attend each other’s weddings and funerals, although the associated split imperils their existence and compromises their livelihood. The community’s lived experiences managing peace and conflict would be tampered with by state-led peace initiatives, which trample grassroots understanding of sustainable peace and everyday resistance.

Anthropologist John Markakis argues that hegemonic understandings of state borders in Africa as products of external impositions ridden with conflict and contradictions, literal and ideational, have resulted in the academic focus on theorizing war for purposes of peace. As a result, peace in the borderland is understood in relation to war, devoid of the political and historical unravelling which shaped it and the inhabitants who strive to reconcile such intermingling. Elite bargains are sought out for peace to prevail, depoliticizing violence, using the same liberal blueprint, which fosters exclusionary politics that masks and perpetuates injustices to retain the status quo. Thus, the aftermath of the Ethio-Eritrea rapprochement was hailed for igniting a regional inertia of peace, engulfing Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia who reaffirmed their commitment to an inclusive regional peace and cooperation. The aim is to secure negative peace, the absence of armed conflict which masks and perpetuates injustices to retain the status quo; while the active rebuilding of social systems to achieve wholesome human relations of equality and justice is the positive peace which is neglected.

Previous analysis of the Horn of Africa entailing state borders splitting territorially bound communities and practices, commonly assumed to be contained geographically, is currently challenged by recent literature in anthropology and human geography which focus on the social, cultural and moral boundaries of borderlands in Africa. Critical anthropologists discredit the notion that all politically recognized state borders in Africa are postcolonial legacies, rather a consideration of human, political, economic, and natural landscapes. Commercial transactions in the borderland bolster informal economies and boost social interaction across state borders. And yet, when the boots of UN peacebuilders stomp the African ground, they trample all the realities carefully managed by people to create an alternative world which fits with the ordained peace. Although physically present within the realities of local inhabitants, they opt for the apolitical interpretations formulated by liberal scripts, which remain unchallenged but disrupt realities on the ground. The subtle but active peacebuilding efforts exhibited by borderland inhabitants such as the Irob to reconcile the deep-rooted animosity created by the 1998–2000 “border war” neither gained recognition as a tool of peacebuilding nor garnered national support or international acclaim.

Borderland inhabitants were the primary recipients of violence induced by the Ethio-Eritrea war, and yet subtle efforts for people-to-people reconciliation transpired during the stalemate. Irob was turned into a garrison area when the hostilities erupted. There was widespread looting of sacred establishments and destruction of private and public property. After the cessation of hostilities, even with their active military involvement in the war, borderland communities underscored the failure of political leadership for having rendered historical, ideological, and economic differences irreconcilable. An act of reciprocity which shapes cross-border social relations is trade. There had been no formal economic trade activity between the two countries for years, and yet border communities shared strong genealogical and socio-economic ties. Consequently, small-scale trade movement (and contraband goods) were active during the two-decade long stalemate, across the Tigray-Eritrea and Afar-Eritrea militarized border. Furthermore, during the brief window in which the Ethiopia-Eritrea border crossing was open after the 2018 rapprochement, trade and commerce were bolstered in border territories, such as Zalambessa.

The opening of the shared borders following the peace deal led to a fourfold increase in the daily influx of Eritreans into Ethiopia. In July 2018, more than 15,000 Eritreans, including women, children and youth, fled the country for a range of reasons, including compulsory National Service, political persecution and a restrictive economy which offers few opportunities. Nonetheless, Tigrayans in Northern Ethiopia warmly welcomed Eritrean refugees mainly due to an understanding of an untainted shared identity which laid the foundation for socio-economic interdependence. An example is the flourishing of a peaceful and mutually benefiting relationship among refugees in Adi Harush (being active economic actors due to high remittances) and host communities in Mai Tsebri as a result of the proximity of the camp to the town, which boosted trade and economic engagement. Conversely, the relation between the Kunama community hosted in the former Shimelba camp is based on labour exchange and agricultural activity, due to the different ethnic composition and language barrier among host and refugee populations. Religious festivities played a pivotal role in strengthening the bond among refugees and host communities with religious institutions often practised by both. Intermarriage between host and refugee populations was also prevalent.

Another grassroots peacebuilding effort is exhibited in Axum’s St. Mary of Zion church, ርዕሰ አድባራት ቅድስተ ቅዱሳን ድንግል ማሪያም ጽዮን, said to harbour the biblical Ark of the Covenant (Tabote Tsion). The annual celebration of St. Mariam Tsion is colourfully celebrated every year on Hidar 21 (November 30) by Orthodox Christian pilgrimages with prayer and worship. For several years, a number of Eritreans are said to have crossed the militarized border to partake in the sacred annual festival which attracts thousands of Orthodox pilgrims from all over the nation. After the peace accord, videos and pictures of Eritreans from Mendefera, who travelled over 100 km to Axum to partake at the annual festivity, were shared widely.

To capture such plurality of peace and the absence of absolute peace, hybrid peace was identified to integrate various mechanisms of peacebuilding from local to transitional peacebuilding processes. Grassroot peacebuilders and local actors are either exoticized and precluded altogether from the peacebuilding process or associated with the implementation of the deal struck by technocrats. Although international processes might ensure accountability while dealing with cases of mass violence, empowered local actors constitute hybridity by deflecting the power embowed within omniscient external perspectives to emanate the hybridity within the local and reclaim the power stripped by technocratic processes. Therefore, peacebuilding techniques must engage with local processes for politics and identity which transpire at a grassroot level. International relations scholar Séverine Autessere examines the shortcomings of the UN Mission to the Democratic Republic of Congo, describing how international complex interventions create peace in a separate world, with its own political and economic spaces. Consequently, the gap between local and international actors expands, creating inequalities, exacerbating preexisting tensions and further fetishizing elites and the system which elevates technocratic approaches.

Nurturing and reproducing a liberal formulae through institutions and individuals supplied with uninterrupted flow of endorsement and investment has rendered peace an industry. Critical international relations scholar Como Siba Grovogui argues that “instead of treating the African condition as evidence that undermines the empirical thesis of a uniform international morality, theorists often construe deviations from the Western state model as a sign of the inability of African states to live up to the requirements of sovereignty”.

The 1998–2000 peace deal was hailed for halting the bloodshed between Ethiopia and Eritrea, but also led to a no-war no-peace impasse which lasted for two decades. Instead of unpacking the shortcomings of hubristic international peacemaking, which dilutes the complicated political and historical dynamics to fit the laden ambitions and intentions of political elites, the failure to implement the script of peace is condemned. The UN’s apprehension over the escalation of death and destruction invokes a political modus operandi which besieges the script of peace rather than moulds the scrip to fit the political. However, not only will atrocities keep unfolding while actors are attempting to implement the process of peace, but also additional violence will emanate as the process has stripped the complexities of the crux of the conflict and carved a dent between politics and people. The Nobel Peace Prize awarded to the Ethiopian leadership for the decisive initiative to resolve the conflict with Eritrea was a symbolic assertion which further contributes to discombobulate the algorithm of politics, for political gain. The politics deemed as conjuncture point to all individuals coming together to determine their faith in unison that is no longer viable.

Problematizing the antithetical positionings of peace and war as either or contributes to demystifying the dominance of Liberal Peace, and the counter-hegemonic practices of peace that reproduce violence. There is a vast pool of research illustrating how liberal peace benefits the state to further its control of territory within a neoliberal political economic set-up and reinforces the continuum of marginalization of ordinary citizens. Both peace agreements between Ethiopia and Eritrea are rational business deals among belligerent parties. The currency at hand is violence which will be dispensed for the ultimate gallant goal of striking a peace deal. If peace is a complex process that requires active efforts to unravel the historical memory of violence and militarized identity, shouldn’t energy be directed at unpacking the differentiated and differentials of conflict for social justice? The failure of the international community to invest in such efforts through grassroots democratic institutions and local inhabitants has amounted to further belligerence. The Ethio-Tigray peacebuilding formulae is a continuation of the Algiers agreement and the 2018 Peace Accord. The process is stripped of politics under the aegis that “only those with the capacity to wage war have the right to determine the terms of the peace.” The ultimate goal is to strike a deal, through a peacebuilding blueprint which absolves war from politics, and disconnects those facing the belligerence from the process that reproduces violence.