Rwanda: A force for good in Mozambique’s “War on Terror”?

While Rwandan troops have helped stabilise the Cabo Delgado conflict, some are concerned by the lack of transparency around their involvement.

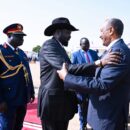

President Paul Kagame of Rwanda welcomes President Filipe Nyusi of Mozambique to Rwanda for a state visit in 2018. Credit: Paul Kagame.

In July 2021, the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) deployed 1,000 soldiers and police officers to northern Mozambique, where, since October 2017, the Mozambican government has been fighting ISIS-linked militants in its gas-rich Cabo Delgado province. To date, the conflict has led to at least 3,700 deaths and the internal displacement of 820,000 people.

Earlier in the conflict, President Filipe Nyusi’s administration spent an estimated $154 million on private military companies such as Russia’s Wagner Group to support the nation’s struggling and poorly equipped military. But this assistance, equipment and training failed to improve the situation. Militants from ISIS-Mozambique continued to grow in strength, capturing towns like the key port city of Mocimboa de Praia and carrying out sporadic attacks along the Tanzanian border.

Alarmed neighbours in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) including South Africa and Tanzania became concerned by the potential for the insurgency to spread across the region and pressured Mozambique to accept its help. Nyusi initially declined and instead turned to Rwanda before later approving an SADC presence.

The RDF made swift progress in their first few weeks, helping Mozambican troops recapture several towns including Mocimboa de Praia, which had been under ISIS-Mozambique control for over a year. Fresh offensives put militant groups on the back foot, forcing them to disperse.

The Rwandans also exported their concept of umuganda (community work) which it had successfully introduced in the Central African Republic where RDF troops have been active as part of the UN mission and under a bilateral agreement. Umuganda involves working with residents in recaptured areas to create a liveable environment through projects such as street cleaning and the rebuilding of infrastructure, which helps stabilise the security situation.

Seven months on from Rwanda’s intervention, which is now made up of around 2,000 troops, there are still violent attacks occurring in Cabo Delgado, but the overall situation has changed significantly. Schools in some areas are re-opening for the first time in years and the French oil and gas major TotalEnergies is preparing to return to its $20 billion liquefied natural gas project.

What’s in it for Rwanda?

Despite its military successes, some observers and opposition groups in Mozambique have raised concerns about Rwanda’s intervention and the reasons behind it. President Nyusi insists Rwanda asked nothing in return for its deployment, and Kigali has said it was motivated to help by the its commitment to the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine and the 2015 Kigali Principles on the Protection of Civilians. But not everyone buys this.

Some opposition parties and civil society groups have questioned whether Nyusi has the constitutional authority to invite in foreign troops without the consent of parliament in the first place. Meanwhile, others have criticised the lack of transparency around Mozambique’s agreement with Rwanda as well as its deals with private military companies before them.

“The concern with Rwanda’s presence in Mozambique is the secrecy in which it has been dealt, not the intervention itself,” says Aldemiro Bande, a journalist working at Mozambique’s Public Integrity Centre (CIP). “Since the beginning, there was no transparency in the deployment of Rwandan troops. The government of Mozambique has failed to provide information to parliament and Mozambican taxpayers on the nature, objectives, financial and political costs of the mission”.

These worries have been elevated by the suggestion that the RDF mission is indirectly supported by France or TotalEnergies, whose multi-billion-dollar LNG project was disrupted by the insecurity. Shortly before Rwanda agreed to send troops, French president Emmanuel Macron made a trip to Kigali in a bid to reset diplomatic ties. During the trip, Macron offered Rwanda a $71 million loan to deal with the pandemic and other forms of support.

Another area of concern relates to Rwanda’s record on human rights and its treatment of political opponents. Both at home and in neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the RDF has a record of systemic violations dating back to the 1990s. In dealing with political opponents, Rwandan security services have been accused of torture, enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention and holding unfair trials.

According to Bande, there have been allegations of abuses in Cabo Delgado by Mozambican soldiers, but not by Rwandan troops. “No case of human rights violations of Mozambican civilians involving Rwandan soldiers have been reported,” he says. “In fact, Rwandan soldiers seem to be better prepared to deal with the civilian population than their Mozambican counterparts”.

However, he raises concerns that Rwandan critics of Kagame based in Mozambique may now be in danger.

“There is a segment [of the opposition] that believes there are secret agreements between the Government of Mozambique and Rwanda which involve natural resources and the delivery by Maputo of the ‘heads’ of Kagame’s political opponents residing in Mozambique,” says Bande.

A force for good?

The stabilisation of the conflict in Mozambique ought to be celebrated. After years of struggling to fight back, the Mozambique Armed Defence Forces (FADM) is finally getting the support it requires and managing to contain insurgency in Cabo Delgado.

At the same time, it should be recognised that the reason Maputo had to turn first to private military companies and then to Rwanda was that it was getting insufficient help from elsewhere. The US provided training missions in March and August 2021. Meanwhile, the European Union established a similar initiative in October and provided €40 million ($45 million) for “non-lethal” equipment such as a field hospital and communications tech. These initiatives were no doubt welcomed by Mozambique yet did little to address the fact that FADM is woefully underequipped.

It is because of this that Nyusi decided to make an opaque deal with Rwanda who, for better or worse, will continue to play a fundamental role in the direction that the conflict takes.