CAR’s surprise release of a war crimes suspect is a blow to justice and peace

The release of government minister Ali from custody is the latest sign of President Touadéra’s disregard for democratic principles.

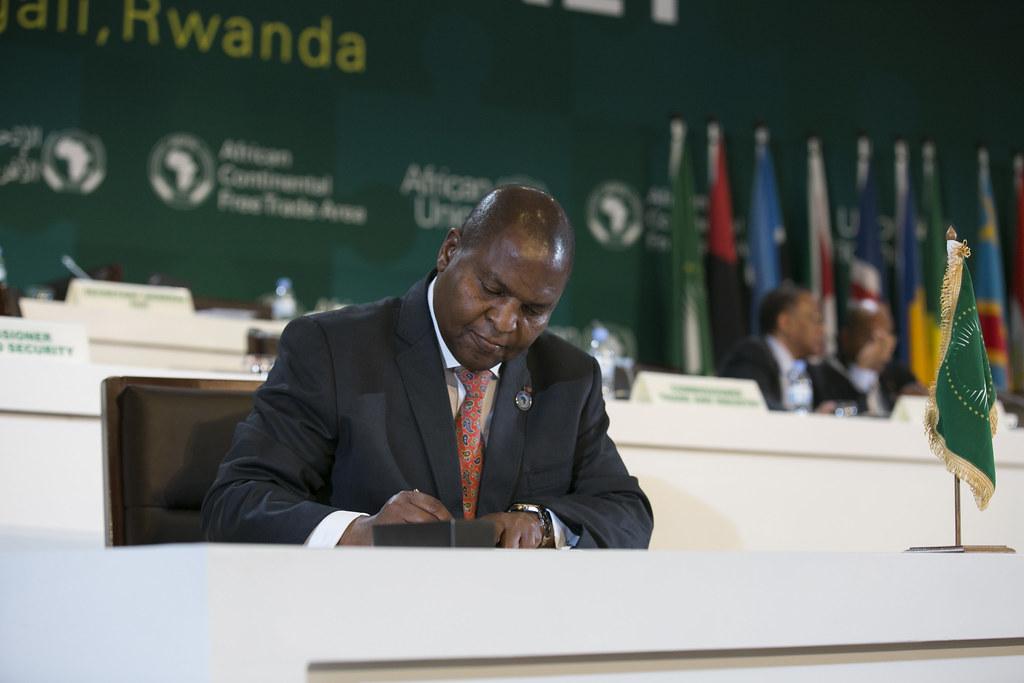

President Touadéra’s ruthless approach in the Central African Republic (CAR) has succeeded in restoring a semblance of stability, but it threatens the prospects for lasting peace. Credit: Paul Kagame.

On 26 November 2021, authorities in the Central African Republic (CAR) unexpectedly released government minister Hassan Bouba Ali from custody. The war crimes suspect had been arrested a week earlier in a major breakthrough for the UN-backed Special Criminal Court (SCC) based in the capital Bangui. Yet just hours before judges were set to rule on whether Bouba’s pre-trial detention should be extended, he was freed.

What does this surprise move mean for the government’s pledge to end impunity? How should we interpret its disregard for a court established to try the most severe human rights abuses committed during CAR’s recent conflict?

Bouba’s rise and rise

The accusations brought against Bouba relate to his time as political coordinator of the Union pour la Paix Centrafricaine (UPC), one of the successor groups of the defunct Séléka rebel alliance whose 2012 attack on Bangui plunged CAR into civil war. While Bouba was in this role, UPC activities led to thousands of civilians being killed, mistreated and displaced. Although the SCC’s case against Bouba does not specify what events prompted the charges, the US NGO The Sentry has identified Bouba as one of the leaders responsible for the massacre of at least 112 people at a displaced persons camp outside Alindao in 2018.

In 2019, Bouba played a central role in negotiations over the peace agreement between the government and armed groups. He was subsequently named political advisor to then Prime Minister Firmin Ngrébada and made himself indispensable to the government. In 2020, President Faustin-Archange Touadéra promoted Bouba, an ethnic Peul with a background in the cattle trade, to Livestock Minister. This went against the wishes of UPC leader Ali Darassa, who later joined the Coalition of Patriots for Change (CPC), a rebel alliance formed in December 2020 to oust President Touadéra. Bouba stuck with the government, making the split with his former ally complete.

This has made the livestock minister even more useful to the government. His intimate knowledge of the UPC is invaluable to Touadéra and the Wagner Group, the Russian paramilitary outfit the government contracted to subdue the rebels. Since falling out with Darassa, Bouba has utilised his former ties to weaken his erstwhile mentor and demobilise UPC combatants. He is also alleged to have orchestrated the assassination of Darassa’s deputy Didier Wangay in December 2021, which prompted a number of UPC generals to disarm. Some former UPC fighters are now rumoured to have been deployed to Mali on behalf of the Wagner Group. Bouba’s worth increased yet further when Darassa was made military chief of the CPC last November.

A blow for justice

For many, Bouba’s rise epitomises a long-established pattern in CAR in which violence and cunning are rewarded with impunity and power. A credible trial against him would have sent a powerful signal that this vicious cycle is coming to an end.

Instead, the government’s defiance of the SCC runs roughshod over the rule of law and undermines the court’s credibility at a time it desperately needs a success. Established in 2015 to prosecute human rights abuses committed since 2002, the SCC held its inaugural hearing in 2018 and became fully operational in 2021. Although it announced in December that its first trial was imminent, it has yet to issue a single sentence. Ordinary Central Africans have not been impressed.

The SCC itself bears some responsibility for this. Recruitment of international staff has been slow, and its outreach and communication strategies leave a lot to be desired. However, the CAR government is mostly to blame for obstructing the court’s work. According to a recent Amnesty International report, only one of the SCC’s 25 arrest warrants – that for Bouba – had been carried out by December 2021. Furthermore, several crimes that fall within the SCC’s jurisdiction have instead been brought before military courts, which are more susceptible to government interference.

Bouba’s release last year doesn’t just make the judges’ work more difficult. It also nourishes a perception that those close to the government are shielded from justice, while those opposed it or deemed inconsequential are fair game. If this impression gains hold, it will be easy to portray the SCC as partisan, negating its efforts toward national reconciliation.

The court’s travails are particularly concerning given that its five-year mandate will expire in 2023 and is renewable only once.

A cycle of discontent

To prevent further harm to the country’s social fabric, the SCC needs its international partners to redouble their support and pressure the government to refrain from further attacks on judicial independence and civil rights.

This includes the UN peacekeeping mission MINUSCA, which has also been discredited by Bangui’s actions. Following Bouba’s arrest, reports emerged of small-scale protests accusing MINUSCA of orchestrating the case to destabilise the government. This, too, follows a pattern in which pro-government media and political organisations propagate a narrative of collusion between UN peacekeepers and rebel groups. This not only hurts popular confidence in MINUSCA but plays into the hands of those calling for cuts to the mission, further weakening checks on the government.

Perhaps most worryingly, Bouba’s release is just the latest in a series of actions that highlight Touadéra’s disregard for institutions and democratic principles. And while large sections of the population support his campaign against rebel groups, discontent has been brewing in opposition quarters and among minorities. This anti-government sentiment has been fuelled by reports of grave human rights abuses committed by Wagner mercenaries; the heavy-handed implementation of a state of emergency; and the Constitutional Court’s ouster of opposition leader Karim Meckassoua from parliament in August, widely regarded as politically motivated.

Touadéra’s ruthless approach has succeeded in restoring a semblance of stability, but it threatens the prospects for lasting peace. While a full-fledged uprising would be even less likely to succeed now than in 2021, mounting rights abuses have fuelled fresh waves of guerrilla-style attacks in the provinces. By perpetuating the cycle of violence and impunity, and by undermining accountability and the potential for reconciliation, the government risks laying the foundation for the next generation of rebel movements.