The International Community Must Reconsider its Engagement with Somaliland

Debating Ideas aims to reflect the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series, publishing engaged, often radical, scholarship, original and activist writing from within the African continent and beyond. It offers debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments books.

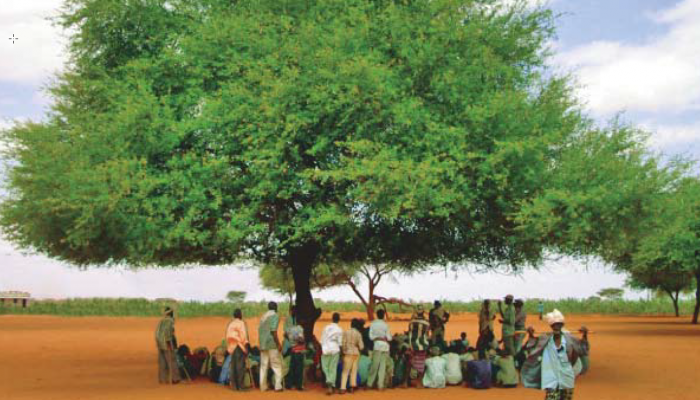

An example of the Somaliland popular justice systems in action.

The root causes of the conflict in Laascaanood are best understood through the intersection of lack of economic development in eastern Somaliland and limited state capacity, eroding the legitimacy of the state. Consequently, the so-called international community should acknowledge that it, indirectly, bears a part of the responsibility for the current conflict in Laascaanood. The way Somaliland is treated by the international community is disgraceful and questions whether the West is genuine when promoting so-called liberal values in the developing world. Somaliland has built on its own what the West is ostensibly willing to wage long, costly, and deadly wars for, e.g., democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. The international community is seemingly not willing to grant Somaliland de jure recognition, denying Somaliland access to global financial bodies. At the same time Somaliland does not receive sufficient financial aid to allow it to cement its legitimacy by increasing provision of public goods and services.

It is my informed contention that the ongoing conflict in Laascaanood could have been avoided if Somaliland had been granted de jure recognition or had access to international funding bodies. The international community should take the recent developments in Somaliland to reconsider its engagement with Somaliland. It is evident that more, rather than less, engagement is needed. However inconvenient, the so-called international community must seriously address the political future of Somaliland, including the question of de jure recognition. The alternative, i.e., ignoring that most people in Somaliland want independent statehood, is not sustainable. Anyone who has visited and travelled in Somaliland will know that voluntary reunification with Somalia is considered beyond the realm of plausibility by most Somalilanders. Somaliland has demonstrated empirical sovereignty for 32 years; how long will the international community ignore Somaliland’s claims to de jure sovereignty? More importantly, is it reasonable and responsible to continue doing so?

External investment and intensifying internal competition?

Applying the ‘resource curse thesis’ to Somaliland, commentators have suggested that ‘accelerating international engagement’ has led to internal clan competition over control of the state, that has come to a head under the current administration. We are, according to this line of reasoning, asked to believe that alleged increased influx of foreign money has had a destabilizing effect on Somaliland. The logic underpinning this argument is that the influx of foreign money is turning the state into a lucrative source of income, rendering it worth fighting for. The evidence marshalled in defence of this assertion is postponement of a general election, which was initially scheduled for November 2022.

Upon closer inspection, however, it appears evident that this line of reasoning does not stand logical scrutiny. Anyone who has seriously studied Somaliland would know that all presidents to date have had their term in office extended (Phillips 2020; Walls 2014). The postponement of the elections in 2022 is, therefore, the rule rather than the exemption. It is, thus, hard to accept the contention that ‘accelerating international engagement’ is causing internal competition for control of the state. To say that the latest postponement of general elections is an expression of internal competition for the control of the state appears untenable as it does not sit comfortably with the historical record. There is nothing indicating that the extension of the current president’s term in power is a hidden attempt to exploit public resources. The current president, Muse Biixi, has indeed earned the nickname of ‘Muse handaraab’,[1] reportedly because of the current administration’s crackdown on embezzlement of public funds. Moreover, if the current delays of elections are attributable to the recent influx of foreign money, what then explains the extensions of previous presidents’ term in office?

Somaliland consolidated peace and built a viable state without external aid

Somaliland’s peace and state building trajectory is characterized by lackof external intervention in the political process. This does not mean, however, that Somaliland was ever isolated against its will and/or rejected by the so-called international community. Rather, social, and political leaders in Somaliland deliberately and freely rejected external involvement in their peace and state building efforts.

The political and security framework of Somaliland was agreed upon during the Borama conference[2] in 1993 (Walls 2014; Bradbury 2008; Phillips 2020). It was also at this conference that a united Somaliland issued a communique to the secretary-general of the United Nations, telling the UN and its forces to stay out of Somaliland. The representatives of the different communities in Somaliland further stressed to the UN that they needed no UN-led facilitation in terms of peace-making. They also stressed that there was no need for the UN to offer food aid protection convoys as Somaliland was not receiving aid. Rather than respecting Somaliland’s desire to be left out of the UN’s framework for peace and state rebuilding in Somalia, the international community, under the guise of the United Nations Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM), did virtually everything possible to disrupt and sabotage Somaliland’s self-led peace and state building efforts (Renders 2012). The tensions between Somaliland and UNOSOM culminated in 1994 where the leader of UNOSOM visited Hargeysa, the capital of Somaliland. He let President Egal know that UNOSOM had competence to deploy troops in Somaliland even without Egal’s consent. To this, Egal replied that if they did so ‘Hargeysa would become the United Nations’ Dien Bien Phu’ (as quoted in Renders 2012: 122), giving him 24 hours to leave Somaliland.

Rather than relying on foreign aid, assistance and expertise, Somaliland chose to rely on its own business communities and diaspora to finance the formation of a state from scratch. Recall that it has recently been suggested that external investments have caused internal competition over control for the state. Yet, it is an empirically verifiable fact that Somaliland, at its darkest hour, rejected international involvement in its peace and state building project, thereby also rejecting foreign aid. Are we supposed to believe that Somaliland rejected foreign aid when it was on its knees, recovering from a devastating civil war but that so-called ‘clans’ are now competing internally because of an external influx of money? If so, what has changed? Bear in mind, that Somaliland receives little direct foreign aid. The bulk of the funds that Somaliland receives, on paper, are often allocated to the salary of foreigners who do little more than occasionally deliver workshops on gender equality and good governance etc. (see Phillips 2020). It is indeed questionable whether the bulk of the 38 million USD promised by Western states will ever be directly managed by the Somaliland state. Commentators rightly observe pervasive perceptions of marginalization in eastern Somaliland, but do not grasp that such perceptions are not caused by internal ‘clan’ competition for control of the state. Inaccurate assumptions often obfuscate conclusions, making it paramount to stress that, if we are to avoid eruption of more conflicts rooted in limitation of state capacity that eventually lead to the questioning or even rejection of state legitimacy, the so-called international community needs to increase its engagement with Somaliland rather than limiting it.

Conclusion

We have already seen tensions in Ceel Afweyn and other conflicts may erupt elsewhere. Effectively remedying the developmental disparity between east and west, giving rise to perceptions of marginalization, is therefore one of the most significant long term challenges facing Somaliland. While it is extreme to suggest that kin-based loyalties have no utility ever in terms of making sense of socio-political relations in Somaliland, it appears rather reductionist and simplistic to excessively focus on the ‘clan’. Other factors do matter and there is indeed some evidence suggesting that kin-based identifications and political behaviour are not always aligned. Dahir Riyaale Kaahin, Somaliland’s third president, hails from the Samaroon group, which makes up circa 10 percent of the population in Somaliland. In 2002 he defeated Ahmed Silanyo, an Issaq,[3] in a free and fair election. Following the logic of clannism, this should have never happened. Barkhad Batuun is currently one of the most well-known and popular politicians in Somaliland. He hails from the Gabooye community, which makes up circa 1–3 percent of the population. Yet, at the latest parliamentary elections he was elected with the highest number of personal votes. Again, this would not have been possible if clannism was as important as some Western commentators, media and academics make it out to be.

It is hard to see how a new and viable state, claiming the regions of Sool, Sanaag and southern Togdheer, can be forged. As soon as such a state would attempt to exert control over these regions, it would face the same challenge as Somaliland is currently facing in Laascaanood, i.e., lack of legitimacy. There are towns and cities throughout these regions where the local population is overwhelmingly pro-Somaliland, e.g., Ceerigaabo, Gar-adag, Caynaba. Consequently, setting up an independent state with Laascaanood as the capital is indeed a political project doomed to fail. With this in mind, Somaliland should pull the national army 30–40 kilometres out of Laascaanood to allow for a viable ceasefire. It is almost certain that Somaliland will not, in the foreseeable future, be able to govern Laascaanood, and any attempt to subdue it, through sheer force, is political suicide. The more people that die in this conflict, the more difficult it will be for Somaliland to reinstate its legitimacy. The optimal and perhaps only reasonable course for Somaliland is to develop a long-term strategy aiming to reincorporate Laascaanood into Somaliland through soft power. The discovery of oil in Somaliland can constitute a new reliable source of income for the state and may usher in a period of prosperity. If managed properly, the revenues of oil can be instrumentalized to bring development to the eastern regions, thereby remedying the pervasive perceptions of marginalization. By doing so, the legitimacy of the state may crystalize throughout the entire country.

The so-called international community must rethink its engagement with Somaliland and face the fact that Somaliland’s claims to independence must be taken seriously. It is neither prudent nor provident to continue with business as usual. Challenges relating to the borders of an independent Somaliland and the like can be pragmatically solved as happened in, for instance, South Sudan. It is rather naïve not to assume that the Mogadishu-based federal Somali state will not attempt to retake Somaliland by force when it is economically and military capable of doing so. The political, economic, and social ramifications of such course of action will prove disastrous for the whole region. A military confrontation between Somaliland and Somalia, that could easily escalate into an all-out war, is inevitable if the West does not seriously reconsider its engagement with Somaliland, including the issue of formal recognition.

End Notes

[1] Handaraab means to close/shut/seal something. In the present context, it refers to public funds.

[2] The Borama Conference began in January 1993 and ended in May 1993. It was attended by representatives from all communities in Somaliland. It produced a security framework for Somaliland together with a governance framework. It was at this conference that Somaliland’s hybrid state was created.

[3] The Issaq make up 70 percent of the population in Somaliland.

References

Bradbury, Mark. Becoming Somaliland. Suffolk: James Currey, 2008.

Renders, Marleen. Consider Somaliland: State building with Traditional Leaders and Institutions. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

Phillips, G. Sarah. When There Was No Aid: War and Peace in Somaliland. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Walls, Michael. A Somali Nation-State: History, Culture, and Somaliland’s Political Transition. Pisa: Ponte Invisible, 2014.

The international community is 100% right not to recognize any new breakaway republics, for that will open a pandora box Africa can hardly afford. Furthermore, the peoples of Sool, Sanaag and Cayn do not wish to break away from Somalia, the international community and somalis know exactly what tribe lives where and indeed the British colonizers made tribal boundaries for each respective tribe inorder to lessen strife and tit for tat raids. The Isaaq clan have crossed those boundaries ever since the British overlords left Somalia, they now wish to lay claim to those regions and proclaim as interlopers to be a majority by exterminating the lesser tribes already there. Thank God for the international community that never recognized such secessionists that perseu ethnic cleansing, truly, no peoples anywhere should take such horrors lightly.

Somaliland is not a breakaway state as you suggest. Somaliland borders are in conformity with the internationally agreed ones. There is no pandora box in recognizing Somaliland and this is clear in the fact-finding report prepared by an AU back in 2005.

The AU fact finding mission in 2005 only visited central and western Somaliland, particularly the cities of Hargeisa, Berbera, Burco, Sheikh and Boorama (as documented in the AU communique related to the mission). It did not approach the regions inhabited by Dhulbahante and Warsangeli (from Buuhoodle to Badhan). This means: diverging voices about the issue of Somaliland’s independence were hardly heard. The conflict over Lasanod, that has been escalating from late Dec. 2022 onward, leading to the current stand-off between the SL army and the armed Dhulbahante inhabitants plus allies from various Harti-clans near the town, is related to the fact that successive Somaliland governments ignored the the will of the majority of the people in what today is known as SSC regions to remain in (a united) Somalia.

the title was rather misleading if not ambiguous. I thought the article was against Somaliland when it wasn’t!

Thanks Markus Hoehne, for all we know the Somaliland government lied to the AU by saying the SSC regions agree with them 100% all the time nothing to see here move along, just as they have been stealing UN funds allocated to the SSC regions for the last two decades, they are beyond corrupt, out right malicious. Now the the SSC regions are directly receiving that humanitarion aid, indeed, the most current administration in Hargeisa is severely plagued by nepotism.

So-called “SSC” is Las Anod and the eastern part of Sool. Tens of thousands of fighters from Darood militas, Al Shabaab, military divisions from Puntland, and the Liyu police have been flooding into the region, yet the people of Sanaag and western Sool remain staunchly in the Somaliland camp as they constitute the majority there.

The world knows the truth, hence the silence from the West and the UN as Somaliland conducts this anti-terrorism operation.

No amount of belly aching from anti-democratic diaspora in Minnesota or their orientalist pseudointellectual spouses will change that reality.

The “SSC” movement is limited to one small area of eastern Sool. Somaliland’s stability in Isaaq-majority cities such as Ceerigaabo, Caynabo, and Ceel Afweyne debunks the anemic pseudoirredentist argument posed by the opponents of stability and democracy in the region.

Somaliland is a nation with or without a seat in the UN.

In the land of Somalia and Somaliland,

There beats a heart that yearns to unite,

A people divided by history’s hand,

Now seeking a future that’s bright.

The wounds of the past still run deep,

But hope springs eternal in the soul,

For a dream of a unified land they keep,

Where every voice can be heard, whole.

From the sandy dunes to the bustling streets,

They march together, hand in hand,

For a land that was once so complete,

And a future where peace can stand.

Oh, Somalia and Somaliland,

May your hearts beat as one again,

For your people are stronger, hand in hand,

And your unity will be a victory, never in vain.

May the past be a teacher and not a chain,

And may forgiveness pave the way,

For a land that’s whole, a people unchained,

And a brighter, better tomorrow, every day.

Let the call of the future be your guide,

And the love for your land be your flame,

For Somalia and Somaliland, united,

Shall forever rise, and always reign.

Fair and well-informed article. Claims of marginalization by the Dulbahante is a red herring. Not only are they still armed but traveling in Sool has always had its risks with their constant inter sub-clan vendettas. I visited the Somaliland republic’s west, east and central by road in 2018 without armed guard but couldn’t risk Las Canood; was impressed by the level of security in the other regions. The west is underdeveloped but yet very peaceful.

What is the West waiting for? Political recognition is a panacea for Somaliland. This will not only stabilize the region but a death knell for Somali Unitarians who want to create a Darod state upto northeastern Kenya.

Ethiopia, Kenya, US and the UK should make a bold decision and ignore the noise ftom Mogadishu which has been surviving on goodwill from the West. It’s the most opportune time now or never.

Somaliland is kaput, the Issa clan declared today they are no more part of it, joining the Dhulbahante and Warsangeli, even within the Isaaq clan there is a growing disavowal of this failed project. Issa tribal elders commanded their soldiers to leave the fighting in Las Anod and return home, over the last few days; SSC fighters have been escorting deserters and wounded, mainly from the Isaaq tribe back to their territories in collaboration with their elders. The Dhulbahante and Warsangeli battling for their territory and warring factionalism in Somalia is as old as time itself, even in the time of Syiad Barre there was fighting, some hiding behind a state, while others in the name of their clan, historically the clan always wins and retains control of their land however long the fighting goes on.

Strange how the non-existent “SSC” Darod clan project has failed.

Dulbahantes are only predominant in Laas Canood. Even outnumbered in various districts of Sool. Sanaag is predominantly Isaaq but has high population of Warsangeli. So under the federal Somali charter can’t form a regional government.

The only viable option for the clan militia is to hold peace talks with Somaliland. And this has come at a very high cost.

Faisal Sheikh yes the Dhulbahante are armed, a hundred years ago up to now they were always armed, even now they delay engagement for the sake of getting flooded with all kinds of arms for free by the Darod, so what? You think you can do better than Imperial Britain or Fascist Italy and disarm the Dhulbahante? If they weren’t armed Somaliland would have taken Las Anod and the rest of Dhulbahante territory.

I don’t think Dhulbahante will get that far with SSC slogan. Sanaage region 80% are Isaak, while 20 % are Warsangali (Darood). Sool region 60% are Dhulbahante and 40% are Isaak. The SSC slogan is a dying slogan and soon Dhulbahante will have a choice ,but to accept the reality on the ground. I my self I welcome this conflict for good reason. SSC and KHatomo slogan their days are numbered. Just like Bob Marley said: You can fool some people sometime, but you can’t fool all the people all the time.

Population of Gadabuursi (samaroon) in Somaliland is 30 percent an isaq is 40 percent Dhulbahante and warsangali 30 percent in Population of Somaliland

The clan borders between the Isaaq and Darod is simple and there is no need to confuse yourselves with percentages for it is as follows; anything west from Buuhoodle city to the town of Laasa-Surad on the gulf of aden is Isaaq, anything east from them is Darod.

Badri Dahir

With all due respect, I don’t know, where did you get that information from ? According to UNDP report in 2022 based in Somalia population report indicated that Somaliland major clans are Isaak , Samaroun, and Harti( Dhulbahante and Warsangali. Isaak are 70% of Somaliland population, the second are 18% Samaroun and 10% are both Dhulbahante and Warsangali and 2% are the rest other minorities. This is not made up story, is a fact from Somalia federal government report.

Firstly, I am really surprised how people in the West, both Somalis and educated, cannot avoid seeing things through clan lenses. I am even more surprised why Western scholars getting involved in all kinds of conflicts in the world. What does Mr Hoehne or any other western scholar have to do with the conflict in Somalia? Somalis have always fought against each other and have also always solved their problems. In my opinion, this conflict should only be an issue for Somalis to discuss and resolve. And as Pro Samatar rightly pointed out, not even IM Lewis, who has been observing Somali for 50 years, has ever been able to understand Somali. https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=8552

Lewis has at least studied all Somalis unlike someone who specifically chose to advocate and support only one sub clan, the sole purpose of this can only be to further divide Somali people.

so called Sool, Sanaag and Cayn ‘SSC’ is fake slogan, Dhulbahante is 7% o Somaliland population, Sool the least populated region of Somaliland Dhulbahante has 45% of population Isaaq has 40% and Fiqishini of Hawiye has the rest 12% other minority are 3%. Dhulbahante has 00% of Sanaag and Cayn is not region but is small district called Buuhoodle of Togdheer region and bordering with Ethiopia, majority of population of Buuhoodle live in Ethiopian side.

Markus Hoahne try to mislead the world with his bias information about Somaliland, may be he don’t like to hear but the fact according 2022 UNDP Report on Somalia 70% of Somaliland population are Isaaq, 18% are Samaroon main tribe, 10% are Dhulbahante and Warsangeli of Daarood main tribe and rest are other minority. So the views and actually the vote of Dhulbahante and Warsangeli are always minority in Somaliland and they should try to get political settlement with their fellow Somalilanders instead they involve endless civil wars with Somaliland majority people, Majeerteen and Sade Daarood could not able to provide regular support to the prolonged wars involved by Dhulbahante.

The fake SSC slogan of Dhulbahante traditional leaders is a failed project, Somali Federal Government, Ethiopia Federal Government, and even other member states of IGAD all reject the ambitions of Dhulbahante Garaad of violation of colonial borders. Furthermore UK, UAE, US and EU show their security concern of ongoing war in Laascaanood. In this context, Dhulbahante will have only one choice ,but to accept the reality on the ground and sit with Somaliland with present of international community, that is the best political venue for Dhulbahante leaders and possible can get political advantage within Somaliland agenda particularly when comes with government structure thought reopen the constitution, sharing national resource and of course rebuilding Sool and Laascaanood to make sure the return of people flee from the war.