Central Africa’s Sovereign Issues: Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe – by Nick Wright

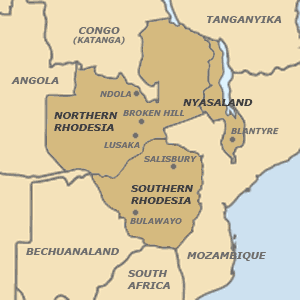

In March 2009, I wrote an article entitled “A New Federation” which suggested that Malawi may be moving slowly, and without anybody really noticing, towards the Federation which had been so firmly rejected by Hastings Banda of Malawi and Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia in the lead-up to Independence. In the 1950s that was the Central African Federation of Northern and Southern Rhodesia, and Nyasaland, promoted by the British colonial power, and emphatically rejected by Banda and Kaunda on the very reasonable grounds that the white government of the regional super-power, Southern. Rhodesia under Sir Roy Welensky, would seek to dominate it.

In March 2009, I wrote an article entitled “A New Federation” which suggested that Malawi may be moving slowly, and without anybody really noticing, towards the Federation which had been so firmly rejected by Hastings Banda of Malawi and Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia in the lead-up to Independence. In the 1950s that was the Central African Federation of Northern and Southern Rhodesia, and Nyasaland, promoted by the British colonial power, and emphatically rejected by Banda and Kaunda on the very reasonable grounds that the white government of the regional super-power, Southern. Rhodesia under Sir Roy Welensky, would seek to dominate it.

By Nick Wright

Not long after writing that article, I was in the Malawian capital, Lilongwe, seeking an interview with President Mutharika. His Press Secretary advised me, with every show of seriousness, to wait by the roadside to see the president’s motorcade that would soon pass from Kamuzu International Airport to State House. I often get into trouble for seeing humour where none was intended — and for missing the jokes when they do come — so I responded cautiously. Was this proposal, I silently wondered, an alternative to the interview I’d requested? Was he telling me not to anticipate the usual privileges that neo-colonial whites in Malawi had come to expect; to take my proper place in the stage-managed and bullying press conferences that local newsmen have to endure? Or was he trying to show me what an important person is the President of Malawi who merits such a long convoy? I still do not know. At that time I took his meaning to be negative.

Suspicion of British “neo-colonialism” within Malawi played a strong part in the eventual collapse of the Federation, in 1962. By a curious irony, it is just such a suspicion within the governments of the successor states of Zimbabwe, Malawi and Zambia that today might impel them towards a revival of the Federation idea.. A generous, and remarkably “string-free”, British aid policy during the post-independence period has been strongly condemned within Mugabe’s circle of friends as an instrument of neo-colonialism . It is showing signs of collapse. It may have been the only thing preventing the formation of an economic federation in this region. Why should these southern African states have surrendered the glories of their own sovereign status when nearly half of their national budgets were being paid-for by international aid donors (of which Britain was the most important)? Only the harsh economic realities of genuine independence could force their hands.

Natural ties between their peoples, together with their own political rhetoric, appear to be pushing these presidents towards the acceptance of that federation which was once anathema to their predecessors and a defining part of their anti-colonial credentials. But have they noticed it?

Recent events offer further encouragement for a reassessment of federalism in this southern African region. Anti-British sentiments are running higher than ever within the governments (though not, I think, the peoples) of all three former-members of the old Federation, fuelled constantly by Robert Mugabe’s burning sense of grievance against Britain. The expulsion from Malawi of British High Commissioner, Fergus Cochrane-Dyet, for appearing to have criticised Mutharika in his mild diplomatic cables to London, is only the most recent of these events.

Sensitivity towards a largely illusory “neo-colonialism” may now become the catalyst for valuable political experimentation. If Malawi is to survive as an aid-free, state, as claimed recently by Mutharika, in a world in which British aid is no longer an automatic economic lifeline, it must begin by sharing some of its precious sovereignty with its neighbours. It must make haste to ally itself with neighbouring African states with which it has obvious affinities and complementary economies.

The Zambian President has already been accused of being a Malawian by parentage and a Zimbabwean in sentiment, and has countered with the accusation that the Opposition leader, Michael Sata, is more of a Tanzanian than a Zambian. Mutharika’s first wife was Zimbabwean; he has property there and an admiring relationship with its President Mugabe. Many Malawians suspect that his sympathies are more Zimbabwean than Malawian. But why all this language of old colonialism? Why shouldn’t they feel as much at home in Zimbabwe, in Malawi and in Zambia? Malawi’s dominant Chewa tribe belongs to all three of them and its major festival is in Zambia. Even the name which Zambia’s current president shares with Malawi’s first is a give-away.

As elsewhere in Africa, porous borders and economic realities have always hinted at the absurdity of tiny sovereignties within the old colonial boundaries of southern Africa. It is no insult to Malawi to suggest that it is a very poor country, and that it is poorer alone than as part of a collectivity. Malawians have always understood, when it comes to the important things in life — like selling off a tobacco crop at a good price, or finding a job — borders are things to be crossed. Even President Mutharika of Malawi must realise that his visionary pet-project to construct an Indian Ocean port at Nsanje, three hundred kilometres from the sea, amidst the mudbanks of the Shire River, can only have some credibility if the other landlocked states of the old Federation get together on this. If Bingu wants to go to sea on a regular basis from Nsanje, and to cross those hundreds of kilometres of Mozambican territory with cargoes of Malawian tobacco, tea and uranium for the world, he must really make haste to add some Zambian copper, and some Zimbabwean nickel and cheese, to that cargo.

Unfortunately, economic and international political realities rarely get the better of presidential hubris when it comes to flags, uniforms, palaces, private jets, VVIP suites, United Nations speeches, and, yes, presidential convoys.. These things which make life so very enjoyable for today’s presidents — and so inconvenient and annoying for everybody else — are too attractive to them. It is hard to think of a modern African presidency without these flummeries. Could any of today’s Zambian, Malawian and Zimbabwean presidents accept the logic of their own angry words against their former colonial power by surrendering some of their paper-thin sovereignties in favour of a workable union?

That will be a serious test for them.

Nick Wright has worked in the History Department at Adelaide University (1975-1991) and for Africa Confidential as its Malawi correspondent (2003-2010).

Interesting thoughts. I would also like to read your 2009 article – where can I access this? My doctoral research explored the experiences of Malawian migrants in colonial urban Zimbabwe from the early 1900s up to the end of the Federation period. I am interested in tracing transnational histories of migration in the region. The connections between these countries are important, but have generally been neglected, despite their potential contribution to discussions on identity, ethnicity, pan-Africanism and more.

Sorry to be so tardy, Zoe. My guess is that the earlier article went into Afr Conf (but that this one is better) Your thesis sounds interesting. Best wishes. Nick