Senegal: Wade regime in the twilight hours? – By Pascal Bianchini

23 June was a day of huge protest in Dakar, with crowds insisting that President Abdoulaye Wade resign (“˜Wade degage!’). The protests were triggered by a constitutional amendment presented to Parliament that would have enabled the head of State to stand for the next elections in 2012 and, most astonishingly, for the winner in the 1st round to get through on only 25% of the votes. Wade wanted to run on a “˜ticket’ with a fellow candidate to become his vice-president (then, the president could replace his vice-president and resign to leave the presidential seat to a newcomer without elections).

23 June was a day of huge protest in Dakar, with crowds insisting that President Abdoulaye Wade resign (“˜Wade degage!’). The protests were triggered by a constitutional amendment presented to Parliament that would have enabled the head of State to stand for the next elections in 2012 and, most astonishingly, for the winner in the 1st round to get through on only 25% of the votes. Wade wanted to run on a “˜ticket’ with a fellow candidate to become his vice-president (then, the president could replace his vice-president and resign to leave the presidential seat to a newcomer without elections).

By Pascal Bianchini

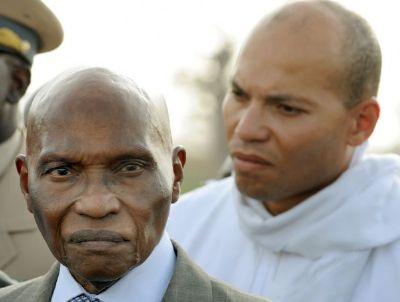

At last, facing a widespread hostile reaction, the president had to give up his plan. The event epitomses the twilight of a regime embedded in deep crisis. Elected in 2000, with the wind of “˜sopi’ (“˜change’ in wolof), “˜Maí®tre Wade’, a liberal, was supported by a heterogeneous coalition that included several leftist parties opposed to the Socialist Party (in power since independence in 1960.) Wade promised a lot when he came in power, but now there is widespread disappointment with the 85 year old leader. The word “˜alternance,’ which had a positive connotation ten years ago, now evokes the “˜nouveaux riches’ even more corrupted than the socialist “˜patrons’ under the previous Abdou Diouf’s regime. Wade’s son, Karim, who holds, concurrently, several portfolios in the government, symbolises the nepotistic character of Wade’s declining regime.

Showcase projects launched by Wade such as the Monument de la Renaissance Africaine or the Third Festival mondial des arts ní¨gres created a little diversion but also attracted much criticism, and have not changed the growing discontent among the population. In the political arena, within a decade, Wade has lost much of the support he won in the run-up to the elections in 2000 and even in 2007. Among the various leftist political parties, from the Parti de l’indépendance et du travail, the Ligue démocratique and more recently Ande Jí«f, Also among the Parti démocratique sénégalais (PDS) – Wade’s own party – some important splits have occurred by prominent figures like Idrissa Seck or Macky Sall, both of them prime ministers and political leaders with grassroots support in their own electoral stronghold (the first is the mayor of Thií¨s and the second of Fatick). Wade’s political base is narrowing since he has stubbornly attempted to impose his son Karim as his heir apparent.

Current political opponents gathered inside a coalition “˜Benno Siggil’ – created before the local elections in 2009 – made major gains in the elections two years ago, especially in Dakar were the PDS led by Karim Wade lost an important battle. For the presidential elections in 2012, Benno with the Parti Socialiste led by Ousmane Tanor Dieng and the Alliance des forces de progrí¨s by Moustapha Niasse, advocates for a single candidate. Nevertheless, there are dissident forces among them, for instance as Talla Sylla, Jí«f Jí«l’s leader who decided recently to create a new Benno “˜Taxaw’ coalition. The opposition is divided. The main difficulty comes from the fact that some parties have sided with the opposition for years while others supported Wade’s government until quite recently. One must also note that the main political force inside Benno remains the PS, the former political party in power for 40 years in Senegal.

Moreover, independent candidates have already said that they will run for the elections, such as Ibrahima Fall, a former minister in Diouf’s governments, or Cheikh Tidiane Gadio, the minister of Foreign Affairs until 2009. Other challengers who were formally in the PDS, such as Idrissa Seck and Macky Sall could do the same.

There is another important dimension: the impetus for change from “˜civil society.’ The recent events have demonstrated the importance of social actors outside the political arena, especially in the suburbs and the “˜quartier populaire’ of the capital. A group of rappers who founded in January a movement called “˜Y’en a marre’ (“˜We are fed up!’) have captured immediately a mass audience among the urban youth mixing artistic and political agit-prop. This protest environment may be viewed as a consequence of the “˜Arab spring’ in Senegal, but it has also its own roots in a strong tradition of collective action, especially with trade unions and students movements, that stretches back decades in Senegal. More recently, in 2008, a new movement emerged against power shortages with demonstrations and refusal to pay for invoices from the company Senelec – interestingly much of this movement was organised by the “˜imams of Guediawaye’, a crowded suburb-slum of Dakar.

Since the epic 23 June, an umbrella organisation has been created (M 23), gathering both the political and the social opposition to the regime. One month later, a successful demonstration was organised. Nevertheless, the regime has been flexing its muscles. New demonstrations are scheduled every month with the inevitable confrontation between the regime and its opponents.

It’s always difficult to foresee how the story will end. But Wade’s power has reached a deadlock. Historical figures from PDS have joined the M23 including Aminata Tall, formerly leader of the women’s organisation of the party, as well as certain intellectuals in the PDS who have openly expressed their hostility to Wade’s third mandate. Many are now saying that he must not be re-elected even with the ndigí¼el (religious order) of the islamic brotherhoods. On the contrary, some of the religious leaders have advised him to compromise with his opponents.

External support (even from France) is no longer guaranteed. Robert Bourgi, a prominent member of the “˜Franí§afrique’ network, made a calculated indiscretion, revealing that Karim Wade had asked him for military intervention from the French. French Minister of Foreign Affairs, Alain Juppé has also expressed implicit criticism. Senegal has always been a “˜vitrine’ (a “˜showcase’) of the French in Africa. Even in the context of a recent direct intervention in Cote d’Ivoire and with some dynastic successions in Togo or Gabon inside the French “˜pré carré (“˜territory’). Senegal should be treated differently, which doesn’t mean indifference: contacts may already exist with some political leaders in a position to bring about the end of Wade’s regime.