Review of Two Zimbabwe Novels: The Boy Next Door and The Trial of Robert Mugabe — Reviewed by James Kilgore

The Boy Next Door by Irene Sabatini, Little Brown and Company, New York, 2009, 403pp.

The Trial of Robert Mugabe by Chielo Zona Eze, Okri Books, Chicago, 2009, 158pp.

Reviewed by James Kilgore

The arrival of these two new voices on the Zimbabwe literary scene is cause for celebration. Both authors offer a nuanced and creative effort to portray the complexities and ultimate degeneration of post-independence Zimbabwe.

Sabatini’s is the more ambitious and conventional of the two. Written in a minimalist style similar to Petina Gappah’s, Sabatini’s debut novel focuses on an unlikely love story between a young coloured girl, Lindiwe Bishop, and her white next door neighbor, the erratic Ian McKenzie.

The novel begins in the early 1980s with Lindiwe still a school girl and spans to the late 90s. Zimbabwe passes through its many twists and turns in the shade of the evolving romance.

Sabatini is at her best depicting the details of Bulawayo and the vagaries of the Fifth Brigade in Matabeleland. The writer has a passion for the charm of Zimbabwe’s second city, an appreciation of each and every storefront and stop street. The images of central Bulawayo strike wonderful chords. Her portrayal of Lindiwe’s family, with the contradictions of long hidden secrets and the brutality of neglect, also resonates. In particular, Lindiwe’s unearthing of the liberation war treachery of an uncle who postures as a heroic guerrilla in the post-1980 years, gives us a clear glimpse into the manufacture of wartime legends. As Lindiwe unearths her uncle’s past, the reader cannot help but think of the military records of the thousands of fraudulent war vets who have climbed on the land-and -payout bandwagon in the last decade.

While she has delivered a comfortable and engrossing read, Sabatini also occasionally stumbles. Though the relationship between Lindiwe and Ian seems credible in the early stages, after Bishop completes university and develops a distinct gender awareness, her ongoing attraction to a classic Rhodesian male who continues to use racial epithets becomes less believable . Lindiwe seems all too eager to forgive at a time in her life where such forgiveness appears out of place. In an interview the author stated that the central question of the book was whether Lindiwe and Ian would “manage to keep this connection.” They do, which may frustrate some readers, as it appears Lindiwe should have moved on. While Lindiwe wouldn’t be the first woman to stay in a relationship long past the sell by date, I wonder how the novel would have worked if the couple had broken up. Perhaps a more authentic reflection of the racial and political tensions of the times would have emerged.

Despite these shortcomings, with The Boy Next Door, Sabatini has established herself as a promising figure among Zimbabwean writers. Though she’s not yet in the league of Vera, Dangarembga or Chinodya, Irene Sabatini is perfectly capable of tackling a broad canvas with fluid prose and considerable insight. Her voice is more than welcome and her ear for dialog is superb.

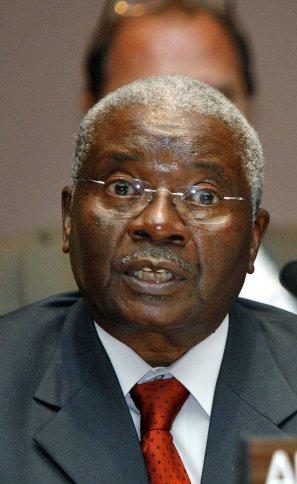

By contrast Chielo Zona Eze is a Nigerian whose clear cut mission is to condemn Mugabe. In a personal communication with the reviewer, Eze labeled the Zimbabwean President as “the epitome of political dysfunction in Africa,… a  symptom of wider phenomena” on the continent. The author possesses a special antipathy for Mugabe’s attempts to “silence his critics and the voice of the people” by blaming all Zimbabwe’s problems on the West. Eze believes it is the duty of African writers to “expose such lies and deception.”

symptom of wider phenomena” on the continent. The author possesses a special antipathy for Mugabe’s attempts to “silence his critics and the voice of the people” by blaming all Zimbabwe’s problems on the West. Eze believes it is the duty of African writers to “expose such lies and deception.”

In keeping with his overtly political purpose, Eze doesn’t hold back. At first The Trial of Robert Mugabe’s premise appears a little absurd. Mugabe sits in heaven at the Final Judgment Day, his fate to be determined by a range of iconic African heroes: Zimbabwean writers Yvonne Vera and Dambudzo Marechera, Steve Biko and Chief Justice Olaudah Equiano, the 18th century Nigerian writer and abolitionist.

Eze cites Ali Mazrui’s The Trial of Christopher Okigbo as his structural inspiration but there are also resonances of Ngugi’s The Trial of Dedan Kemathi and the transcripts of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa. The author could have gotten into trouble with this trial setting, but he manages to make it work.

Drawing extensively on the powerful testimony by witnesses to the atrocities in Matabeleland, Eze chronicles the Fifth Brigade’s military campaign with unforgiving frankness and extensive graphic detail. At times, The Trial runs like a well-constructed history of Mugabe’s years in power, with the testimony serving as lively and authentic source material.

Eze’s strength lies in his international and Pan-African vision. By including Biko and Equiano among those who sit in judgment, Mugabe’s trial becomes not merely an event for Zimbabwe but one that places human rights violations under ZANU-PF into a continental and global context.

While there is much of interest in The Trial, at times the plot line does run a little thin. The conclusion is a little bit too foregone, yet for anyone who wants to get a glimpse of Mugabe’s underside, minus the self-serving diatribes of a Catherine Buckle or Eric Harrison, The Trial of Robert Mugabe is a valuable and easy read. The events of the legal proceedings flow smoothly and Eze ultimately presents an optimistic message: that justice in Africa is part of universal notions of justice and will ultimately triumph. Sadly, as Dobrota Pucherova pointed out in her review of the book, Eze’s trial may be the only one Mugabe ever faces. Perhaps that makes the work all the more worth reading.

The reviewer is an Affiliated Research Scholar at the University of Illinois (Champaign-Urbana) and the author of the 2009 novel We Are All Zimbabweans Now.