Democratic change in West Africa – Senegal and Guinea Bissau go to the polls – By Peter Howes, analyst at Risk Resolution Group

In the next week, two very different elections will take place in two neighbouring but divergent West African states. Both Senegal’s presidential run-off and the Guinea Bissau elections have wide external importance. Here’s why.

Generalisations

This year, there will be around 20 African countries holding national elections and institutional investors regularly cite democratic stability as a factor in appraisals of a country’s investment climate. Often, such appraisals are made (rightly or wrongly) on a regional basis; if Senegal is seen to become semi-autocratic, the confidence of potential West African investors (particularly those without previous market expertise) could be affected.

A slight aside: various studies have shown that expropriation (for instance) has historically occurred more regularly under democratic governments, so perhaps linear reliance on democracy to determine favourable market investment conditions is a little unreliable.

Nonetheless, potential foreign investment is regularly influenced by both empirical analysis, and by broad impressions of regional issues such as “˜democracy in West Africa’ or “˜conflict in the Horn’. Commentators, seeking macro-level conclusions, talk of 2012 as “˜the year free elections could come to Africa’ or link potential political liberalisation to the Arab Spring. Both these broad “˜impressions’ and continent-wide progress are surprisingly important, and for this reason alone, every African election has external ramifications.

Secondly, principles of interconnectedness aside, democratisation breeds democratisation, and if two of the states polling this year hold seemingly free elections, the possible catalytic effects across West Africa (or indeed across la Francophonie) shouldn’t be underestimated, with Mali, Gambia, Sierra Leone and Burkina Faso all holding elections themselves later in the year.

Democratic continuity

The proof of a successful democracy is not in initial democratisation, or in one set of free elections after years of instability, but the ability to see one ruling elite relinquish power, and this process to be repeated time and again. Sustained democracy is not a short-term race. In Senegal, Presidents Senghor and Diouf were in power for 20 and 19 years respectively – each implementing slow democratic reforms. Wade’s contribution to the democratic war effort was a term limit, but the true test for Senegal will be consistent power transfers. In Guinea Bissau, the test is for the state to prove that political assassinations and stories of control by narcotic cartels can be relegated to memory. Again, despite relative stability during Malam Bacai Sanhá’s term in office, the true test lies in continuity. Sanha’s short term in office was not a complete success by any means, but after the election in July 2009 until mid-2010, there were few notable events, indicating the capacity for another successful election to provide at least temporary calm.

Senegal

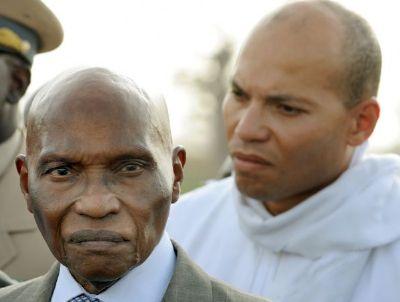

Senegal has been much-discussed over the last few months – even though interested observers were denied the rather surreal theatrics of a potential run-off between multi-award-winning musician Youssou N’Dour and 85-year-old incumbent Abdoulaye Wade.

With Wade seemingly preparing one of the least subtle democratic familial successions in recent memory (son Karim holds a wide portfolio of ministerial titles), Senegal faces a test of democratic continuity. Abdoulaye himself introduced the two-term limit, and his claim that it did not apply retroactively is a legal point, albeit an unpopular one: he is seen as increasingly unrepresentative of a populace with an average age of under 20. The wider concern is of succession: it is not impossible to foresee Karim installed as president, with a fresh two term limit. There is an endgame, however; Karim is rather less electable than his father: his French education has compelled many Senegalese to view him as an outsider – with additional distrust accrued through his ostensibly un-earned ministerial titles. Under current conditions, therefore, it is difficult to foresee presidential power in the hands of the Wades beyond one further electoral cycle.

Many were surprised by how consolidated the Senegalese opposition were in the first presidential round. The very real risk of no stand-out candidates emerging and pushing the vote to a second round run-off was allayed by the emergence of Macky Sall, providing those disappointed by the lack of a Wade/N’Dour run-off with the theatrics of a political master/apprentice duel. However, many commentators are perhaps oversimplifying by expecting all votes for previous opposition candidates (around 39%) to be consolidated around Sall,– for many, his APR party bears too many similarities to Wade’s PDS. Whether we can expect the vast majority of Socialist Party/Alliance for the Forces of Progress voters to vote for Sall in the second round remains unclear. On a side note, a single transferable vote mechanism would seem to be a more logical electoral system for Senegal than the current two round, single-vote mechanism, also in use in Guinea Bissau.

Guinea Bissau

Guinea Bissau, for a country with a small population and a land area well under half of that of Scotland, is immensely complicated. With a GDP per capita of around USD$ 1100, it remains one of the poorest countries in the world. Many see the drugs trade – which seemingly took a hiatus from the international agenda (outside of Latin America at least) for a couple of years – returning to the fore in the form of so-called “˜narco-states’. Guinea Bissau has been regularly cited since 2005 as Africa’s first (actual or potential) such state, with its loose border control, Latin American ties and Atlantic location making it a prime target for smugglers targeting the major European cocaine market. The term appears made for Bissau, with the country’s GDP insignificant in comparison with the street value of the cocaine which passes through. Indeed, the events of 2009 seemed more akin to those of a cartel than a national government, with Sanha’s predecessor Joao Bernardo Vieira assassinated in an apparent drugs-linked revenge attack for the earlier death of the army head, General Batista Tagme Na Waie. Plagued by instability since independence from Portugal in the early 1970s, Guinea Bissau’s apparent short-term stability was severely tested by Sanha’s death of natural causes at the start of this year.

With a large field of candidates in the March 18 election, it is likely that support will be similarly diluted as in Senegal’s first presidential round. The exact number of candidates is in fact unclear: the Supreme Court noted that it had received 15 applications for candidacy, but AFP and the UN noted that there would be nine names on ballot papers.

The stand-out name is perhaps Carlos Gomez Junior – the former Prime Minister – whose arrest in mid-2010 by the army illustrates the need for any president to keep the military on-side. Bissau’s political make-up is interesting, with independent candidates able to attract sizeable vote shares (in 2009, independent candidate Henrique Pereira Rosa garnered over 20% of the votes cast). The candidates’ list reads like a who’s who of Bissau’s recent history: other high-profile candidates include current defence minister Baciro Djá and former president Kumba Ialá (leader of the PRS party; deposed in a coup). Henrique Rosa was interim president between 2003 and 2005, implemented various democratic reforms and handed over power efficiently to (later assassinated) President Vieira, and as such could be a major challenger once more. With under 500,000 votes expected and such a broad selection of candidates, predictions are difficult. Ruling party PAIGC is backing Carlos Gomez Junior, and his success or otherwise could be a barometer as to the public perception of Sanha’s presidency. Interestingly, the country’s flag is based on that of PAIGC, with controversy over the flag’s possible appearance on ballot papers. With links between the PAIGC, the army and the Balanta ethnic group (numbering 30% of the population), as elsewhere, there is a tribal element to the election – although Ialá himself is Balanta. Ialá, Junior and Rosa can each be expected to each acquire sizeable vote shares.

International interest in Guinea Bissau has always dwarfed its relatively small population – Angola has substantial interests in country, and there is of course the narcotics angle

The question of post-election violence is an uncertain one: recent controversy over voter registration and allegations of governmental corruption could see potential flare-ups (as indeed seen in a February 20th demonstration in central Bissau), but as ever, Guinea Bissau is sure to provide further surprises. Seemingly, Ban-Ki Moon expects trouble, with his statement calling on “˜national stakeholders, including the government, political parties, civil society and the population as a whole, to ensure that the poll takes place in a peaceful, orderly and transparent manner‘.

Both Senegal and Guinea Bissau must prove that their respective transitions to democracy are complete, therefore. Two further additions to the effective democracies grouping will passively engender further democratisation, but disputed elections or other electoral issues could have international ramifications. Additionally, stable governments in both could lead to bilateral progress on mutual issues such as maritime borders and the trafficking of drugs and people between their respective states.

Peter Howes is an analyst at Risk Resolution Group