Senegal and Mali: Thoughts on West African democracy – By Dayo Olaide

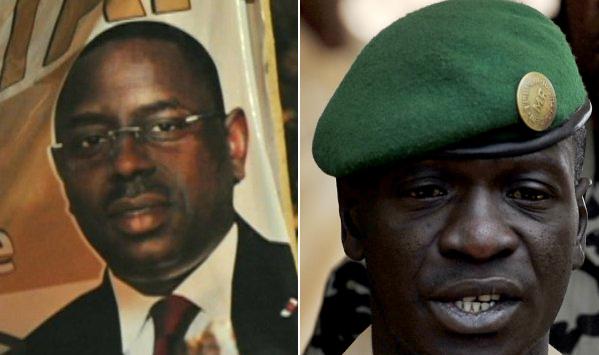

Over the two months, the state of West African democracy has been tested on several occasions. In Senegal, after second round elections, citizens elected a new president, their once Prime Minister Macky Sall. In Mali, Coupists, led by Captain Amadou Sanogo, overthrew elected President Amadou Toumani Toure (ATT), even though presidential elections were originally scheduled for April 19. And in Guinea Bissau a chaotic military junta has grabbed hold of power in the face of civilian political challenge to its ascendancy. All are pivotal events for the region and the continent. They are keystone markers that may reveal as much about the ardent need to preserve and build democracy in Africa, as the precarious and fragile foundation on which it is built.

The elections in Senegal and the coup in Mali hold many lessons for West Africa’s new democracies. A truly democratic culture must be spread across electoral institutions, processes, practices and actors, as exemplified in the lead up and eventual outcome of the recent Senegalese elections. In June 2011, Senegal’s President Wade attempted an illegal constitutional coup when he tried to remove term limits in office and reduce the percentage needed to win from 50 percent plus 1 to 25 percent. It would have been his fifteenth amendment to the constitution. The Senegalese refused, rallying together to stop the amendment, and coalescing to form a civil movement, the M-23. This latter group would later be at the helm of citizen-driven campaigns against Wade’s bid.

In hindsight, had this 15th constitutional change gone through Wade and his team would have already been sipping champagne at the end of the first round elections, when Wade won 34 percent of the votes. It was clear early on that Wade controlled the Constitutional Council, even before the February 26th round. The Council had overthrown the bid of Youssou N’dour, the popular musician with a great youth appeal, on the grounds that he did not have the sufficient 10,000 signatures required to be in the presidential race. In the end, preserving democracy became the responsibility of all Senegalese citizens. They used non-violent means, advocated by Y en a marre (a youth-led civil movement), to mobilize voters against Wade’s plans for re-election. This tandem (and timely) effort of a united opposition and an engaged citizenry may serve as a valuable lesson for other countries.

The firm belief of Senegalese people in the power of a democratic electoral process sets a good example for Sierra Leoneans who are facing upcoming elections in November. The present political climate in the country is dangerously polarized, inching towards a precipice. Much work is needed to address the prevalent mood of distrust and help boost electoral confidence to avoid any outbreak of major violence.

The second important lesson lies in the nexus of what took place in Senegal and Mali. Certainly, democracy in Africa benefits from a number of important frameworks on elections and governance. An inherent goal is the promotion of constitutional order and succession through the ballot boxes. While military coups may be more “˜traditional’ ways of overthrowing governments, the practice of the “˜civilian coup’, as attempted by Wade, is becoming very serious, and an oft overlooked danger. In Africa, it is dangerous for any government to stay longer than two terms against constitutional provisions.

A situation whereby the elected President runs for limitless terms in office – as the case in Niger, Cameroun, Chad, Burkina Faso and Gabon – must be condemned. A “˜civilian coup’ can be as serious and damaging as a military coup d’états. Sadly, the silence and failure of the AU, ECOWAS and other various regional commission bodies to sanction these acts emboldens other African heads of states and raises questions about the usefulness and effectiveness of such organizations. In Niger, former President Mamadou Tandja used the parliament to rubber stamp the outcome of a discredited referendum and was only stopped by a counter military coup. In Chad, President Idris Derby removed term limits (with the acquiescence of a biased parliament) and is now serving his fourth term. In Nigeria, Olusegun Obasanjo’s attempt was foiled only by a resilient Nigerian population. In Cameroun, Paul Biya has become a lifelong President. And the story continues in Burkina Faso, Gabon, Uganda and Zimbabwe. None of these civilian coups have been sanctioned by AU or any RECs.

In Mali, the coupists justified their acts by saying ATT was “˜incompetent’ – this reflects the larger inability for democracy to meet expectations of economic and political freedom in other parts of Africa. In Senegal, the nationwide mood for change stems from the corruption and mismanagement that has greatly deprived and impoverished its people. In Mali, it stems from ATT’s failure to provide adequate funding and equipment to confront Tuareg militants and protect the country’s sovereignty. Both cases point to a common problem facing African democracies – rather than deliver economic freedom, presidents, governors and mayors privatise state resources to service their families and friends while immiserating their citizens.

Both events this past week are clear indications that it is time for deep reflections on the meaning of democracy. From Senegal to Nigeria, Mali to Mauritania, Benin to Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea to Togo, citizens in West Africa are in search of the benefits of democracy that go beyond the rituals of regular voting every four to seven years.

As demonstrated in Senegal, the livelihood of democracy lies with three essential ingredients. First, citizens must be schooled in democratic principles so they can play an active role in protecting democracy against anti-democratic forces. Second, political parties must be transparent and accountable. And finally, Africa needs a vigilant and bold AU and regional commission that will protect the sanctity of democratic frameworks, norms and practices. Meeting these conditions will not only keep Africa on its path towards democracy, but also help ensure its political, social and economic development for the future.

Oladayo Olaide is the Economic Governance Program Manger at the Open Society Initiative for West Africa (OSIWA).

SENEGAL CAN TEACH THE WORLD MUCH ABOUT DEMOCRACY

Written by BRAD BROWN

Sunday, 15 April 2012

At 9:30 p.m. March 26, Senegal’s President Abdulaye Wade, 85, running for his third term after 12 years in office, called his former Prime Minister Macky Sall, 50, to congratulate him on his electoral victory and wish him well. Sall’s statement emphasized that he would be president of all the people.

In many African countries, a sitting president has never been defeated by a vote. This election in Senegal was nonviolent, fair and transparent. It was a far cry from the naysayers who spoke of possible fraud, violence, coups and worse.

French and U.S. diplomatic staff urged Wade not to run. This was a mistake.

In democracies, people should not only be able to achieve power but also be able to lose it by a vote of the people, not by resignations through arm-twisting. The professionalism of the Senegal military and the devotion shown to democracy by Wade over his long career would prevail.

The election marks a shift from the generation that brought independence to those who have grown up since then. Senegal has never had a coup. After 20 years, the first president, Léopold Senghor, stepped down and Prime Minister Abdou Diouf succeeded him. Diouf was defeated in an election after 20 years in office by Wade.

That is an enviable democratic record but it was not achieved without struggle.

From the first prime minister, under Senghor, Mamadou Moustapha Dia, who when seen a threat to presidential power in 1962 , was removed and sentenced to life in prison, to Sall, who was dismissed as prime minister but is now president, Senegal’s democracy has come a long way.

Critical to that achievement is Wade, who, when Senegal was a one-party state, urged democracy and, when an opening was made to allow other parties to exist besides the ruling Socialists, Wade formed the Democratic Party of Senegal in 1974.

Wade ran for the presidency and lost several times. He was jailed twice after elections as a threat to the state. He also served as a minister briefly in two governments as part of a coalition. During that long period when his party struggled to survive, never was there any attempt at a coup or to push for resignations due to unfair elections. Finally, in 2000, he came in second in the first round and forced a runoff which he won. He was re-elected in 2005.

During Wade’s tenure, there were local elections, which are run nationally and his party lost numerous contests, including his son’s bid for office. By not resigning, by having the government run a fair election and by making that phone call to Sall, he demonstrated his commitment to, and Senegal’s capacity for, democratic governance that a withdrawal under pressure would never have done.

President Barack Obama congratulated Sall on his election and also praised Wade’s leadership.

There is no question that the development of Senegal expanded under Wade but he was running in a world economy which is having severe impact on food and oil prices. Even achievements such as increasing educational opportunities were confounded by the reality of more university graduates now having difficulty in finding jobs.

Wade said he would lead his party into the upcoming parliamentary elections to solidify a loyal opposition, again another step towards strengthening democracy. Sall, a geologist, brings scientific insights into development and the political skills he honed as a minister and prime minister under Wade should serve him well.

We wish him success in solidifying Senegal as a mid-income country and producing development with a safety net for those most in need.

Brad Brown is a retired National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientist. He continues to work as a consultant on African coastal and marine projects and scientific capacity development. He is also first vice president of the Miami-Dade NAACP. He may be reached at [email protected]

published in South Florida Times Newspaper