Rwanda in Congo: Sixteen Years of Intervention – By William Macpherson

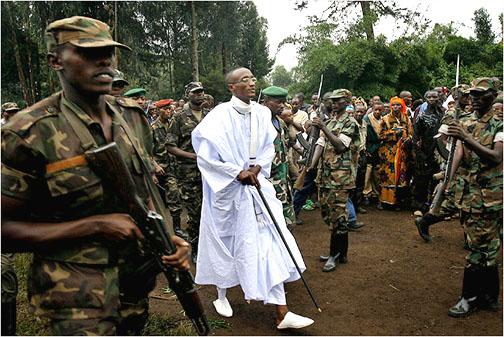

Laurent Nkunda - dressed, Messiah-like in white - whose Congolese Tutsi forces were previously given Rwandan support, symbolises neighbourly meddling in the DRC.

A recent UN report on the crisis in eastern DRC indicates that senior members of the Rwandan military have been supporting Congo’s newest rebel outfit, M23. Such revelations hold true to a familiar pattern that has seen Rwanda play a significant and controversial role in Congolese history since 1996.

Over the past sixteen years, the presence of aggressive Hutu militias in the Kivus has encouraged Rwanda to play the role of regional policeman in an attempt to protect both its own borders and vulnerable Congolese Tutsi. That said, opportunistic strategies of personal and national accumulation, displayed particularly during the Second Congo War, have left Rwandan leaders susceptible to the accusation that their agenda in the DRC is somewhat more Machiavellian. As a result, the Rwandan government has often been accused of spoiling Congolese peace as a means to pursue its own ends.

Hutu Militias, Border Protection and the Congolese Tutsi

A central justification for Rwandan military activity in the DRC has been the threat posed, both to border security, but also to Congolese Tutsi, by Hutu militias based in the DRC. Often, the Kinshasa government’s inability to provide effective security in the Kivus against these groups has been used to justify the use of Rwandan force.

The Impact of the 1994 Genocide

After the 1994 Genocide, the victory of the Tutsi dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front (“RPF”) brought about a change in government in Kigali. The remnants of Rwanda’s genocidal former government, alongside Interhamwe and other members of the Hutu power movement fled west into North and South Kivu. Upon arrival, these groups, sustained by the massive influx of humanitarian aid, were able to regroup and coordinate deadly cross-border raids into their homeland. By 2000, these groups had formed the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) which continues to fight in eastern Congo to this day.

The Congolese Tutsi

Congolese Tutsi, descendants of various waves of migration that date back as far as the late 19th century, have been vulnerable to attack from Hutu rebels, but also from indigenous Congolese militias, hostile to Tutsi influence in the Kivus. Congo’s Tutsi population continues to be subject to violent attack and on the receiving end of militant exclusionary rhetoric. Rapid population growth has compounded issues of land scarcity, in turn consolidating ethnic divides. As Mobutu Sese Seko took reluctant steps towards democratisation in the early nineties, ethnic divides and antagonisms were aggravated by the opening up of the political space and the ethnic mobilisation that inevitably accompanies the promise of elections. Congolese Tutsi were increasingly referred to as “˜foreigners’. Ethnic violence exploded in the Kivus in the early nineties with the proliferation of Mai Mai militias, in league with Hutu forces, determined to protect their own interests and traditional rights. Such violence continues sporadically to this day. Furthermore, the international community’s indifference to the plight of thousands of Tutsi during the 1994 genocide, has encouraged the claim that if Rwanda does not protect the Congolese Tutsi, no one will.

Such issues have informed Rwandan actions in the DRC since 1996. They make up official justifications for the presence of the Rwandan military in the DRC.

The Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (AFDL)

Paul Kagame, now President of Rwanda, justified Rwanda’s backing of Laurent-Désiré Kabila’s AFDL, eventually to overthrow Mobutu in May 1997, on these grounds. Formally portrayed as a Banyamulenge (South Kivutian Congolese Tutsi) uprising, the insurrection was, in reality, driven across Zaire by Rwandan guns, troops and money. Along the way, the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA, now RDF, Rwandan Defence Forces) dismantled the Hutu dominated refugee camps in the most brutal of fashions, allegedly causing the deaths of thousands of civilians in the process.

Since the AFDL rebellion, the logic of border security and the protection of Tutsi have been used to justify Rwandan military support for Tutsi dominated Congolese rebel groups. Prominent amongst these are the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD) and Laurent Nkunda’s National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP), the descendent of which is M23.

The Promise of Plunder and the Second Congo War

Rwandan intervention has, at times, proven more Machiavellian. Most notably during the Second Congo War, Rwandan control over large swathes of eastern Congo was capitalised upon for personal and national enrichment.

The Second Congo War

Once installed in Kinshasa, Kabila’s relationship with his Rwandan benefactors quickly soured. To many Congolese, the new president was a Rwandan puppet, enthroned by eastern foreigners bent on the subjugation of all under universal Tutsi rule. Lacking legitimacy, and in need of a PR boost, Kabila dismissed his Rwandan Chief of Staff, James Kabarebe, and expelled all foreign troops from Congolese soil. This act precipitated Congo’s descent into five years of conflict that would see the deaths of over 3.8 million Congolese: the Great War of Africa.

Fearful of losing influence, and alert to rumours that Kabila was supporting Hutu and Mai Mai militias in the Kivus, both Rwanda and Uganda backed another rebellion in the east. However, Kabila’s strength was bolstered by an alliance with Zimbabwe, Angola and Namibia, later to be joined by the governments of Chad, Sudan and Libya. By September 1998, fighting had reached a stalemate. This ensured the de facto partition of the DRC. Kabila and his allies controlled the south and west. Rwanda and Uganda dominated the east through their respective proxies, the RCD and Movement for the Liberation of Congo (MLC).

The Theft of Congolese Resources

Until the summer of 2002, senior members of the Rwandan armed forces would plunder the DRC’s mineral reserves, achieving great personal wealth and enriching their homeland. The figures speak for themselves. Rwandan diamond exports increased from 166 carats in 1998 to 30,500 two years later. In 2000, revenue from coltan – a metal used in the manufacture of electronic products – was thought to amount to US$ 80-100 million, equivalent to official defence expenditure. A UN panel of experts found that during 1999 and 2000, the RPA made US$250 million in the space of eighteen months.

Similarly, senior members of the Rwandan military made a fortune at a personal level. In August 1999, the Ugandan People’s Defence Force (UPDF) and Rwandan military, supposed allies, clashed in Kisangani. The battle is thought to have been caused by antagonisms over the control of diamond fields. In 2001, the UN Security Council condemned this activity as the illegal “˜plunder of Congo’s resources’.

The partition of the DRC was effectively brought to an end by the signing of the Pretoria Accords in July 2002. This agreement provided for the withdrawal of 20,000 Rwandan troops and for renewed commitment from the government of Joseph Kabila (who succeeded his assassinated father in 2001) to tackle FDLR militia in the east

Covert Support for General Laurent Nkunda

Since the signing of the Pretoria Accords, Rwanda has officially withdrawn its military from the DRC. However, the political reasons for Rwanda’s initial involvement have not abated. The FDLR was still at large and militia groups continued to threaten Congolese Tutsi communities. It is perhaps for this reason that Rwanda has been accused on numerous occasions since 2002 of funding and supporting dissident rebel groups in the DRC. It seems clear that Rwanda maintained a covert presence in the Kivus through its proxy RCD – Goma. A UN report found that in June 2004, senior members of the Rwandan military provided support for the mutiny of Colonel Mutebutsi, a Banyamulenge, and General Nkunda, a Tutsi from North Kivu, in Bukavu.

Laurent Nkunda was to prove a consistent spoiler of the fragile peace. In December of 2004, Nkunda and Tutsi forces attacked the town of Kanyabayonga on the Rwandan border. In 2006, he attacked the town of Rutshuru. By August of 2007, Nkunda had taken control of much of North Kivu, setting up an alternative government and a new movement, the CNDP. In 2008, Nkunda attacked the city of Goma, displacing some 250,000 people. Throughout this time, the Rwandan government has consistently been accused of supporting Nkunda.

An Unexpected Rapprochement and the Origins of M23

In 2009, Kinshasa approached Kigali with the aim of negotiating the integration of the CNDP into FARDC (the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo). As part of the deal, the RDF was granted access to Congolese territory in order to neutralise the FDLR. ICC indicted General Bosco Ntaganda wrested control from Nkunda and the CNDP was integrated into FARDC. In January of the same year, Nkunda was arrested in Rwanda.

Ntaganda maintained a parallel command structure, and many former members of the CNDP enjoyed privileges such as deployment to rich mining areas. For many, M23 represents an attempt to maintain these privileges, rather than being driven by actual grievances with regards to the implementation of the deal (M23 refers to the date of the agreement between the CNDP and Kinshasa, 23rd March 2009).

Divided opinion

It is the opinion of many that the Rwandan government has consistently supported the activities of Nkunda and the CNDP. Filip Reyntjens, an expert on the Great Lakes region, argues that senior members of the Rwandan government have sought to undermine the Congolese peace process in order to conserve their own political and economic influence over eastern DRC. René Lemarchand, another regional expert, argues that the strength of Rwanda’s military is dependent on Congolese resources. In this way, the RDF represents a powerful force demanding involvement in Congolese affairs.

Others take a different view. Andrew Mwenda, a prominent Ugandan journalist, has recently argued that senior members of the Kagame regime have been willing to turn a blind eye to those within Rwanda who wish to provide support to Tutsi dissident groups in the DRC. Mwenda makes it clear that the threat to Rwandan borders and Congolese Tutsi in the form of the FDLR is still very real. In the absence of an effective Congolese state, capable of policing its eastern most extremities, the Rwandan government needs these groups to work as buffers to protect its borders.

Recurrent Dynamics

The UN report referred to at the start of this article accuses Rwanda of supplying ammunition, guns, healthcare, training and new recruits to M23 alongside other militia groups in the region. James Kabarebe, Rwanda’s Defence Minister General, is said to have played a prominent role in organising support for the rebels. Allegedly, Nkunda, supposedly incarcerated in Gisenyi, has attended several M23 meetings.

Revelations of Rwandan support for Tutsi rebels in the DRC do not represent a new trend. It seems likely that such patterns of involvement will continue whilst the Congolese state has little control over the Kivus. Such a vacuum of power offers opportunities for those that benefit from insecurity, whether they are Hutu rebels, or members of the Rwandan armed forces in pursuit of personal enrichment.

Main Groups/Players

Militia Groups

National Congress for the Defence of the People, (CNDP)

Rebel group formed in 2007 by Laurent Nkunda. The movement controlled large parts of North Kivu until 2009. Setting up an alternative government, the CNDP proclaimed its intention to deliver community projects and its intention to protect the Congolese Tutsi. In 2009, leadership was taken over by Bosco Ntaganda and CNDP troops were integrated into FARDC. The bulk of M23 members are former CNDP fighters.

Rally for Congolese Democracy – Goma, (RCD – Goma)

The RCD formed the basis of the rebellion that sparked the Second Congo War. In 1999, the movement split into two factions: RCD – Goma and RCD – Liberation Movement. These were supported by Rwanda and Uganda respectively until around 2003. RCD – Goma is also a political party. Its representative, Azarias Ruberwa served as Vice President of the DRC until the 2006 elections. The party has had little success since.

The Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda – (FDLR)

A Hutu militia formed in 2000, the FDLR counts former genocidaires amongst its number. The group is the descendant of the Hutu Power movement that fled Rwanda after the victory of the RPF in 1994. The FDLR is a declining, yet considerable military presence in the Kivus. It targets Congolese Tutsi communities and hopes, someday, to return to power in Rwanda.

Mai Mai militias

The Mai Mai refer, not to one militia specifically, but to the many indigenous Congolese armed groups active in eastern Congo. These groups are largely concerned about local antagonisms such as access to land. They are notorious for the fickle nature of their allegiances.

People

Laurent Nkunda

Congolese Tutsi and former rebel leader, Nkunda has served with the RPA, AFDL and RCD. Following the Second Congo War, the Global and All-Inclusive Agreement attempted to integrate rebel groups into the Congolese armed forces. Nkunda refused, citing safety fears. He retreated into the hills of North Kivu with Tutsi troops. Nkunda controlled large swathes of North Kivu, setting up an alternative government. In 2009, he was arrested by the Rwandan military.

James Kabarebe

Currently Rwandan Minister for Defence, James Kabarebe has been a senior figure in the Rwandan military for many years. Kabarebe was the commanding officer of the AFDL in 1996-7. Allegedly, he has played a significant role in orchestrating support for M23.

In 1998, Kabarebe is rumoured to have been involved in a failed attempt to assassinate Laurent – Désiré Kabila.

Bosco Ntaganda

Nicknamed “˜the Terminator’ for his brutality, Bosco Ntaganda is wanted by the ICC for crimes committed in Ituri between 2002 and 2003. Ntaganda took control of the CNDP in 2009 as part of a Rwandan – Congolese deal that saw the arrest of Nkunda. He is thought to be leading the M23 rebellion. Ntaganda is a Congolese Tutsi and former member of the RPA.

William Macpherson has previously written for Think Africa Press.

[…] Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) which continues to fight in eastern Congo to this day. Â Read more… Share this:ShareTwitterFacebookLike this:LikeBe the first to like this. This entry was posted in […]