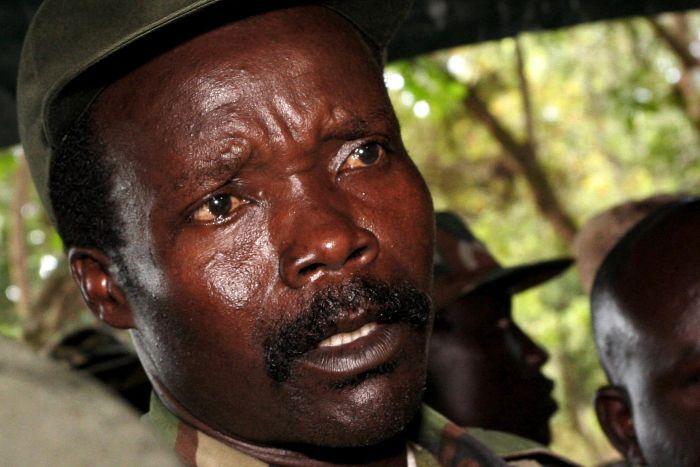

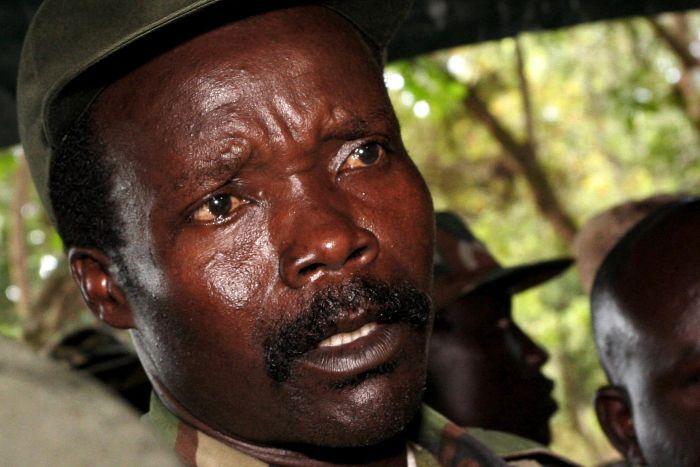

In the wake of Kony: peace versus justice in Uganda – By Carter Newman

Joseph Kony may be gone from northern Uganda but his legacy continues to disrupt northern Uganda as returnees are left unsupported and in limbo while Amnesty and Transitional Justice are wrangled over.

2012 was the year NGO Invisible Children’s “˜Stop Kony’ campaign focused attention on the man himself and his militia, the Lord’s Resistance Army. But after decades of conflict, neglect and the mass displacement of the civilian population, many communities in northern, eastern and north-western Uganda are suffering economically, socially and politically. Instead of expending international and national resources hunting down Kony, the security and prosperity of people on the ground should be the real focus.

Justice and reconciliation is a hot topic but has yet to take shape in Uganda. The Amnesty Act gave impunity to LRA operatives and affiliates, absolving them of any crimes they might have committed while in the bush and promised no punishment on their homecoming. The Act that played such a significant role in bringing peace to northern Uganda has been amended and may further be removed. In theory, some form of national transitional justice policy will replace it; the argument is that now peace has taken hold, it is time for justice and accountability to replace impunity. However, the outcry in Uganda over the recent changes to the Amnesty Act seemed to catch the amenders by surprise; there is still a demand for amnesty.

On May 23rd, 2012 the decision was made to allow Part 2 of the act to lapse, meaning that amnesty is no longer granted to new returnees. This decision makes new returnees liable to prosecution by Ugandan courts of law. But opinions are polarized around this change; some believe it paves the way for accountability and reconciliation in Uganda. Others that it flies in the face of the underpinnings of the Amnesty Act; which leaders in the North strove for when they had to fight hard for it in the first place.

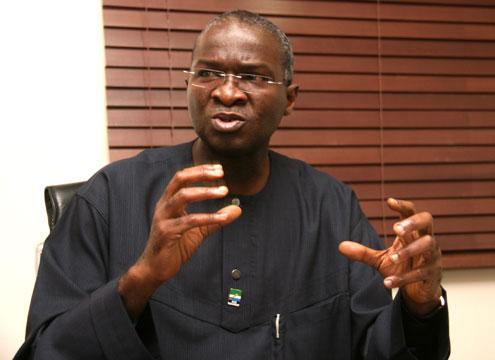

The reaction of many to the changes in the Amnesty Act was dismay, due partially to misunderstanding the changes, misreading the removal of Part 2 as removing the amnesty given to all returnees in Uganda. This is not the case. It is only applicable to new returnees. The government has not, however, done a great job of communicating the changes of the Amnesty Act to the general public, especially in the north. Even a statement explaining the changes made by James Baba, Minister of State for Internal Affairs, is not particularly easy to understand.

The statement justified the changes made by referring to the Juba Agreement on Accountability and Reconciliation and the fact that it affords victims rights to accountability. Baba’s statement also said that the decision was “informed by a Justice Law and Order Sector review of the Amnesty law which revealed that the grant of unconditional amnesty was generally seen as problematic since it did not take into account the need for accountability for serious crimes committed during armed conflict or rebellion.”

I am intrigued by the use of the term “generally seen”. Whose perspective is this from? I understand there is a push for accountability, and although it was provided for in the full pre-2012 Amnesty Act, it has not been implemented. Thomas Kwoyelo is a case in point, the first LRA rebel on trial for crimes committed whilst in the LRA, abducted as a boy, he successfully argued that prosecution was unlawful given his Amnesty certificate. Has a decision been made that enough help has been given to the returnees and now it is time to start helping the victims? Or is it a push to comply with international demands for “˜justice’?

A retired bishop in northern Uganda, Bishop Ochola, delivered a petition, signed by many community leaders in, calling for the reinstatement of Amnesty Act in full (including the amnesty bit). The religious leader explains that they do not want to see amnesty thrown away without something to replace it. At present there is no transitional justice policy to stand in Amnesty’s stead. He also stated what northern Ugandan leaders want is reconciliation in the communities through community-based collective responsibility, not “western-style prosecution”. Here the question of who wants what resurfaces; demands change with expectations, from struggling to survive, to prospering, to demanding justice. But is this process necessarily sequential and inevitable? It depends who you ask; whether they are vulnerable females, marginalized groups, community leaders or any other pre-assigned group.

Which terms are used in this debate is key to understanding the motivations of those behind them: amnesty, accountability, justice and reconciliation. What is needed and what is in demand in northern Uganda, and what is being driven from Kampala? Is there still a need for reintegration and resettlement assistance? Has there been too much focus on this and is it time for justice and accountability? But whose justice and what kind of accountability? Who will be involved in this process?

What returnee assistance?

In James Baba’s statement, in lieu of providing Amnesty, he states, “the Commission will continue with its reintegration, resettlement, demobilization, disarmament and reconciliation mandate for the period of the extension.” For Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR), aside from scaring away new returnees, the changes in the Amnesty Act theoretically mean that every ex-combatant is entitled to reintegration support irrespective of whether they reported into the Amnesty Commission or not. This is a positive step for returnees not liable to prosecution. However, can you be guilty (or at least liable to prosecution) and receive reintegration support?

I wonder how prosecution and reintegration support will play out. Many returnees have not registered with the Amnesty Commission as reporters, because they do not feel guilty, in fact they are indignant that they should be labeled as a perpetrator guilty of various acts when they themselves were victims of abduction. Ruth, a formerly abducted child-mother, does not feel she needs to be absolved from her crimes because it was the state and the community who failed to protect her from abduction. Amnesty implies blame, which in many cases, is simply not recognized.

More importantly, how is the state going to provide reintegration assistance to a wider field of candidates when, to date, it has barely been able to assist? A cynic might say that the review of the Amnesty Act comes at a good time, since there is no money to provide reintegration support, irrespective of whether it is embezzled by the Office of the Prime Minister. In the last couple of years, assistance from the Amnesty Commission has floundered.

Resettlement assistance in the form of reinsertion packets was stopped in 2011 when the Multi-Demobilization and Reintegration Program (World Bank funded) was completed. As of 2012, reintegration support has been provided to 5,335 reporters, with 20,984 still to receive assistance. The issue of reintegration and resettlement assistance is a quagmire; the Amnesty Commission has provided different forms of assistance over the years. Reintegration support at first took the form of reintegration packets, then eight vocational courses and now community dialogue sensitization meetings. However, this assistance is not reaching many returnees.

For the Amnesty Demobilization and Resettlement Team (DRT) in Kitgum, the majority of reintegration packets were given out in 2006-07 when MDRP funding was there. External funding is no longer available and for the financial year 2011 – 2012 the Amnesty Commission DRT office in Kitgum provided three community training sessions to 60 people, of which 40 were “˜formerly abducted’ and 20 were “˜from the community’. If you are looking at reintegration support that means the government provided some form of support to 120 returnees for that financial year for nine districts in northern Uganda. For the financial year 2012 – 2013, the same DRT office provided one dialog and sensitivity meeting for 30 people. Giving the benefit of the doubt that they were all returnees, three quarters of the way through this financial year, 30 returnees have been talked to by the Amnesty Commission office for Kitgum, covering the districts of Kitgum, Pader, Lamwo, Agago, Otuke, Lira, Amolatar, Dokolo, Albetong.

For reintegration and resettlement assistance there is still demand both from new returnees and from those returned but who are yet to receive anything. Formerly abducted people are still returning, the LRA Crisis Tracker 2012 Annual Security Brief records 31 returnees in 2012, 16 in 2011, and 35 in 2010. These numbers are much smaller than those recorded by official reception services. Gulu Support the Children Organisation (GUSCO) recorded 73 returnees in 2010 and 29 in 2011 (even with 9 months of data missing from January 2011 to September 2011). These numbers begin to show you how difficult it is to know how many returnees there have been and how many are still expected.

If these numbers are added to the 20,984 officially recorded returnees who have not yet received reintegration support from the Amnesty, you have a lot of returnees who have received nothing despite commitments made by the Government of Uganda.

The Amnesty Act is due for renewal in May, before this brouhaha many anticipated it would not be renewed, there is little to no activity by the Amnesty Commission itself as it sits in limbo, without funding and without political will. However, the public protest around the revised Amnesty Act means that it may well be resurrected, but who it will actually help and what it will do is uncertain. The distinction between peace and justice is a political one. It is the affected communities who will determine whether peace and justice have really been accomplished. Uganda is in a unique position to reframe this debate.

Carter Newman is a researcher and writer, currently working on social development and transitional justice issues in post-conflict northern Uganda.

[…] An article on how Amnesty is dealing with returnee assistance. […]

[…] In the Wake of Kony: peace versus justice in Uganda […]