CAR: Seleka regroups; UN deployment can’t come soon enough – By Hanna Ucko Neill

Following the resignation of CAR President Michel Djotodia in January 2014, former Seleka rebels loyal to Djotodia withdrew, some say fled, north. His resignation triggered several months of unprecedented violence in the CAR, the brutality of which shocked the world. Predominantly Christian vigilantes, known as the anti-Balaka, began killing mostly Muslim civilians in revenge for the brutal attacks carried out by Seleka rebels leading up to, during and after their coup in March 2013.

The pattern of violence typically saw anti-Balaka militia involved in the lynching, mutilation and even cannibalism of Muslim civilians. The African-led International Support Mission to the Central African Republic (MISCA) and 2,000 French troops struggled to protect civilians in the face of such widespread violence. Thousands have been killed and about 25% of the country’s 4.6 million people have been displaced. The international community condemned the violence and after several months of prevarication, the United Nations Security Council decided to deploy a peacekeeping mission to the war-torn country.

The international community and the media focused primarily on violence perpetrated by the anti-Balaka, warnings of genocide, the politics surrounding the evacuation of Muslims to safety, and the delay in the deployment of peacekeepers. Attempts were made to understand the structure of the newly formed anti-Balaka militia, its leadership and supporters.

Meanwhile, the former Seleka fighters have regrouped, both politically and militarily. The nature of violence also appears to have changed. Since April, an increasing number of reports suggest former Seleka rebels are engaging the anti-Balaka in battle. In April and May, clashes were reported in Dekoa, 300 km north of Bangui, where over 80 people were killed and several others wounded in clashes between the two armed groups. Seleka fighters reportedly carried out attacks or were involved in clashes in the north in Dekoa, Paoua, Bouca, Kaga Bandoro and Mala in the north, in Bari in the east, in north-eastern Grimari and south-western Gamboula. Reports also emerged that former Seleka fighters were attacking villagers along the border with Cameroon.

In one of the more audacious attacks, Seleka fighters attacked a hospital supported by Médecins sans Frontií¨res (MSF) in the Boguila region, killing at least 16 people. The attack took place on the 26th April, when Seleka fighters assaulted the compound while health workers met with community leaders. Unprovoked, the armed men opened fire into the crowd. MSF is the only external aid group providing health services in CAR and has since suspended its activities.

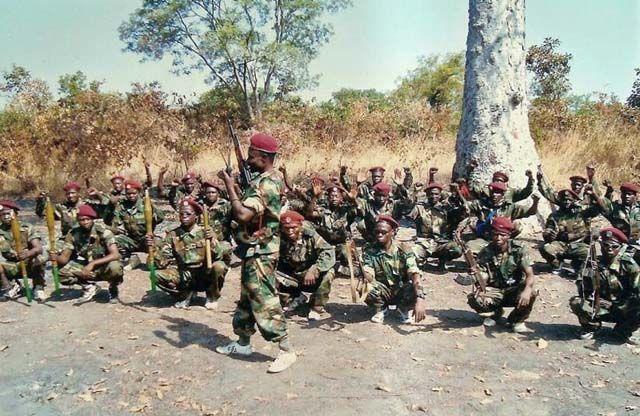

On the 10th May, several hundred members of the Seleka met and named Gen. Joseph Zindeko as their new military commander. The group chose as its headquarters Bambari, a town near the dividing line between the Christian south and mostly Muslim north. According to the group, the new chain of command is simply an attempt to unite its fragmented fighters in the north, creating a credible interlocutor for the government to deal with. It is as yet unclear what kind of leverage Zindeko will have on the group and what path it will follow; it is not the first time that someone has attempted to claim leadership over the fragmented group.

The government meanwhile appears sceptical that the regrouping is simply a means to curb violence. On the 20th May, the government of Catherine Samba-Panza condemned the move, saying the group has seized state property in the north. Its irregular forces have been accused of effectively creating a parallel army and police force in areas under its control. Prime Minister Andre Nzapayake warned that recent moves by the group are “˜nothing less than an attempt for a partition of the country’. Various Seleka spokesmen have called for the partition of CAR into two states, one Muslim and one Christian. Samba-Panza and the international community remain firmly opposed to breaking the country up along religious lines.

There is also some concern at the establishment of the new militia Organisation of the Central African Muslim Resistance (ORMC), set up by one of Djotodia’s former aides. ORMC is reportedly a coalition group comprised of three movements, the Union of Democratic Forces for Unity – the party of Djotodia, the Movement of Central African Liberators for Justice, and the Organisation of Islamic Youth. Some sources have suggested that the group consists of some 5,000 well-equipped men. Fears include the possibility that radical Islamist groups could infiltrate the ORMC to establish a new base. CAR fits the failed-state model often targeted by Islamists groups and its ideology could easily take root amongst frustrated fighters. The UN has said that there is already some evidence that Nigerian Islamist group Boko Haram, present in Cameroon, may have sought sanctuary in unpopulated and ungoverned areas of CAR.

The UN has pledged to send some 12,000 peacekeepers to the CAR. However, no date has been set for the deployment. Further delays may make a UN deployment futile. It is not inconceivable that when UN forces eventually deploy, the situation on the ground may have changed to such a degree that the prevention of ethnically motivated violence is no longer enough. Rather, they may be faced with the daunting task of tackling an all-out civil war.

Hanna Ucko Neill is Global Conflict Analyst at the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS). Twitter: @HannaUckoNeill

I think this article contains some insights but is quite crude in its analysis; I am based in CAR and have traveled across the country talking to communities. CAR does not neatly break down into the ‘Christian south’ and ‘mostly Muslim’ north as stated by Hanna Ucko Neil; communities across this country have been mixed for generations, which is part of the narrative of this complex conflict. MSF has not suspended all its activities, and continues to work in projects across the country. The UN deployment is scheduled for September and UN staff are arriving here every week. We need to explore the rationales of non-state actors embedded in this conflict, and what it will take for them to stand back from violence that has become their raison d’entre, not merely repeat the tired old cry of looming catastrophic civil war and Boko Harm. This week Banguiois have pulled themselves back from the brink of all-out street violence, and we need to explore how, and why, they did so in order to understand these conflict dynamics.

This analysis contains several factual mistakes. First of all, there was one act of cannibalism in Bangui from a deranged person who had lost most his family members at the hand of ex Seleka soldiers. I don’t think he was an “anti Balaka†and I am not trying to defend anti Balakas or Selekas. In Bangui, people call him “mad dog.â€

Second, when you write that “MSF is the only external aid group providing health services in CAR†is factually wrong. You just have to travel to Bangui to see that there are several NGOs providing health services.

Last, just to clarify, the UNDPKO is schedule to have troops on the ground in September. Whether or not, it happens is another story but a date was given.

Thanks

What is not said in any so-called analysis is which imperial or regonal powers are behind Seleka. We know France brought these guys to power in the first place. Who running the show behind the scenes to get the diamonds etc, now?

Any shortfalls in analysis are well covered by the above respondents. The authors concluding comment regarding the inexplicable delays in deployment of a UN peacekeeping mission reveal a real crisis in UN peacekeeping. No doubt that it has evolved into an inert, incompetent and wholly ineffective body.