Live from Bangui: Why Inclusive Dialogue Matters in CAR – By Louisa Waugh

Last June, when I first arrived in the Central African Republic (CAR), one of the resident ex-pats suggested I visit “˜Cinq Kilo’ – Bangui’s largest market. “˜It’s rowdy, but fun.’ He said. “˜Take someone local with you; it’s famous for pickpockets too.’ I liked the market, and soon felt confident enough to take one of the shared yellow public taxis back there alone. Speaking Arabic helped me bargain, as the vast majority of traders in Cinq Kilo were Muslim.

Last June, when I first arrived in the Central African Republic (CAR), one of the resident ex-pats suggested I visit “˜Cinq Kilo’ – Bangui’s largest market. “˜It’s rowdy, but fun.’ He said. “˜Take someone local with you; it’s famous for pickpockets too.’ I liked the market, and soon felt confident enough to take one of the shared yellow public taxis back there alone. Speaking Arabic helped me bargain, as the vast majority of traders in Cinq Kilo were Muslim.

Six months later anti-Balaka fighters attacked Bangui, effectively overthrowing the resident Seleka regime. Anti-Balaka commanders talked to me about “˜Liberating’ CAR from the violent excesses of Seleka, saying they had nothing against ordinary Muslims. But their own fighters dumped corpses with slit throats outside Mosques in Cinq Kilo, and Muslim businesses were looted en masse. Inter-communal violence spewed across Bangui for months. Cinq Kilo and its neighbourhoods became Bangui’s “˜No-go Zone’.

Fifteen hundred French “˜Sangaris’ soldiers, and thousands of troops deployed from the African Union struggled to control the violence, or to win the trust of local people, wary of foreign political agendas, especially the French. A curfew was introduced to try and limit the endless car-jacking, armed burglaries and other rising street crimes. By nightfall most streets were so quiet they looked, and felt, haunted.

In light of all this, the recent (relative) calm in Bangui has been almost unnerving, and virtually unreported. Last week I returned to Cinq Kilo for the first time in months; and was quietly stunned to see the market coming back to life. I spoke with a dozen Muslim traders. They all said things were improving. “˜We can move around day and evening now’ one man in traditional robes told me. “˜We’re not in fear anymore; no-one is menacing us.’

As we talked, a heavily armed EUFOR patrol drove slowly along the main street of the market. The troops, Estonians, spoke no French, but they too agreed security was getting better.

EUFOR is the European Union’s “˜bridging mission,’ now at full capacity, with 800 troops based in Bangui until UN peacekeepers are scheduled to take over, mid-way through September. EUFOR’s mission is focussed on securing Bangui’s traditional Muslim Arrondissements, or neighbourhoods, like Cinq Kilo, to encourage the depleted local Muslim population to return.

And it seems to be working.

This tentative revival of the near-abandoned Muslim quarters of Bangui is partly due to consistent military patrols. But also to a shift in public perception of this crisis by many Bangui residents, which has been virtually unreported too: for the last few months a mass public information campaign has been reinforcing the message that all Central Africans belong here, and local social cohesion projects are re-opening spaces where Muslims and Christians, especially youth, are beginning to feel safe to come together, just as people are beginning to come together in Cinq Kilo.

Some of these projects are run by international NGOs, many others by local civil society organisations, who have also taken risks in bringing together groups of local Seleka and anti-Balaka fighters, and initiating contact between them. These local initiatives are another reason Cinq Kilo is now opening for business, and why security has improved in many parts of Bangui. This small capital is still plagued by tensions and crime, especially at night outside the city centre; but dialogue between communities has started.

And this, ironically, is why the National Forum of Central African Reconciliation, opening on Monday July 21st in Congo Brazzaville, is already in trouble. Many Central African civil society activists have refused to attend the 2 day forum, which aims to kick-start national reconciliation between the CAR government and rebel groups. But Seleka and anti-Balaka are still fighting each (and killing civilians, especially outside Bangui), neither side has agreed to either a complete cessation of hostilities, nor full disarmament before these talks.

Some civil society activists wonder where the sanctions against impunity are – and why these talks are not being held in situ in Bangui, where they would be more accountable to the national population?

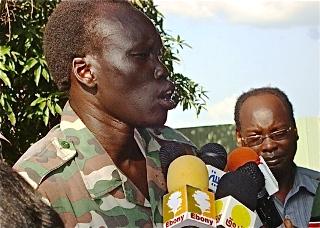

Anti-Balaka coordinator, Patrice Edward Ngaisonna will be in Brazzaville on Monday, as will Seleka’s Vice President Mohamed Moussa Dhafane (though it’s doubtful Seleka’s new leader, the ex-President of CAR Michel D’Jotodia, will appear, as he is under ICC investigation into alleged war crimes). CAR President Catherine Samba-Panza is attending too, with members of her transitional government, though many are also apparently refusing to go, for much the same reasons as CAR’s civil society activists.

It’s easy to criticise Catherine Samba-Panza for this flawed attempt at national reconciliation (though the whiff of foreign interference doesn’t help; Samba-Panza was unceremoniously told to leave the recent AU contact group meeting when CAR was discussed) but she is in a difficult and tenuous position, given CAR’s dependence on foreign powers that have their own political agendas for this country, including its potential wealth in natural resources.

The question facing these forum delegates now is whether it’s truly in the long-suffering national interest to engage with Seleka and anti-Balaka at this level, before they have committed themselves to stop killing Central Africans. Until both movements are held to account at local and national level, and commit to non-violent and inclusive political dialogue, nothing is really going to change. If members of Seleka and anti-Balaka are subsequently offered positions in the transitional government, this will effectively reward their violations, and continue the frightening levels of impunity across CAR.

The appalling violence of these last twelve months has never been about Christians versus Muslims; it stemmed from fear between neighbours and communities familiar with living together, but easily manipulated by Seleka, anti-Balaka, and other armed rebels who appropriated their vicious brands of identity based politics for their own ends.

The Central African civil society challenge is about communities holding the government to account. A local human rights advocate said these words to me just last week; “˜Some people here are not ready to give their pardon, because they still hear nothing about justice.’

Louisa Waugh is Central African project manager for Conciliation Resources (based in Bangui). She is the author of 3 books.