Regionalisation, Israeli Support and the Anyanya in South Sudan – Book Review by Brian Adeba

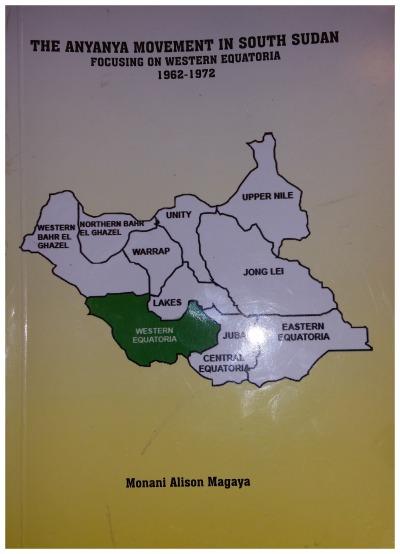

Review of: Monani Alison Magaya, The Anyanya Movement in South Sudan, Focusing on Western Equatoria, 1962-1972, Marianum Press Ltd, Kisubi, Uganda, 2015

In a tale all too familiar to many South Sudanese of his generation, General Monani Alison Magaya begins this book with the 1962 student strike that precipitated a mass exodus of young Southerners into exile in neighbouring countries.

After the strike shut down operations at Rumbek Secondary School, Magaya returned to his hometown of Maridi in Western Equatoria. This was the time when General Ibrahim Abboud’s repressive southern policy was in full swing.

The 16-year-old Magaya and a cousin faced constant harassment from the regime’s security apparatus. Both hightailed it out of town, becoming refugees in the Congo (present day DRC).

But in Congo, where thousands of South Sudanese refugees resided, a nascent plot for an armed insurrection led by Fr. Saturnino Lohure, the father of South Sudanese liberation politics, was in the works. Here, a turning point occurs for the young Magaya as he becomes politicised and is drawn into the armed struggle.

As any scholar of South Sudanese history is aware, there are numerous works on the Anyanya movement, authored mostly by foreign writers. Overall, the narrative of local actors in the Anyanya movement is largely missing.

However, Joseph Lagu’s Sudan: Odyssey Through a State, From Ruin to Hope, Severino Fuli’s Shaping a Free Southern Sudan: Memoirs of our Struggle 1934-1985 and Elijah Malok Aleng’s The Southern Sudan: Struggle for Liberty have attempted to fill the indigenous literary barrenness on the Anyanya.

Whereas Lagu focuses on the overall evolution of the Anyanya, and Fuli and Aleng shed light on the behind-the-scenes activities in Uganda and on the ground, Magaya traces the origins of the movement in Western Equatoria. And in that sense, this book is unique. It sheds light on history, key actors of the Anyanya in Western Equatoria and the civil administration set up by the rebels.

Two key themes emerge from his account.

The first theme is one that any scholar of the Anyanya Movement is aware of: that the Anyanya were a disparate group of peasant soldiers lacking a central command and a cohesive political ideology. In Western Equatoria, the picture that emerges from Magaya’s book is one of organised and dedicated guerillas, almost akin to the partisans in Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls.

Here, readers are shown an organisation with a locally organised hierarchical military structure, albeit lacking political sophistication beyond wanting to drive the Arabs from their land. We see a self-reliant military organisation, whose main quartermaster was the civilian population with whom it had built amicable relations.

Although he dedicates ample space to how this “independence” of the Western Equatorian fighters prevailed, Magaya is silent on explaining how the lack of a central command fostered the birth of regionalisation and even ethnicisation, two themes that would later permeate and define the liberation struggle in South Sudan.

At its most basic, this regionalisation entailed that soldiers should fight in their home areas and not anywhere else in Southern Sudan, for better or worse. Perhaps there were practical reasons behind this policy, but Magaya does not care to explain. As such, Western Equatorian military leaders like Magaya, Samuel Abu John, Habakuk Soro, Dominic Kassiano, John Masua, Isaiah Paul, Dominic Dabi, William Bangafu, Samson Wasara, David Lewe and the famous Ali Gbatala mainly fought on their home turf.

An even closer scrutiny reveals that the Azande leaders fought in areas around their villages or hometowns, while the non-Azande like Ali Gbatala, John Masua and David Lewe, for example, were mainly based in non-Azande areas in present-day Maridi County. Sometimes, the Azande leaders were not even allowed command in locales that they were not native to.

A case in point is when Ismail Sidigi and Kelliopa Mene dislodged Magaya and Captain Dominic Kassiano from Naangere military camp in September 1965. This event happened after Magaya and Kassiano ambushed a convoy of trucks belonging to a Greek trader from Yambio called Dmitri, looting his goods ostensibly to punish him for his “closer cooperation with the enemy forces.”

Magaya subsequently cites two reasons behind the move to forcefully relieve them of command in Naangere: jealousy over the looted goods and “there was also an ultra sectarian motive because the two happened to be the sons of the area while we were not.” Sometimes this regionalisation was extended to other Southern Sudanese fighters, ostensibly to maintain law and order.

Magaya subsequently cites two reasons behind the move to forcefully relieve them of command in Naangere: jealousy over the looted goods and “there was also an ultra sectarian motive because the two happened to be the sons of the area while we were not.” Sometimes this regionalisation was extended to other Southern Sudanese fighters, ostensibly to maintain law and order.

It is worth mentioning that Western Equatoria’s proximity to the Congo border meant that it was a strategic location for accessing arms from the Simba rebellion of the 1960s. As such, transit camps for receiving arms and ammunition for fighters in Bahr El Ghazel operated in Western Equatoria. But in 1968, the Western Equatoria regional command ordered the destruction of one such camp at Sakure, commanded by Captain Kerbino Kuanyin Bol, who was accused of looting, and mistreating the local population.

Captain Dominic Kassiano was assigned the task. And here’s where the adage “˜history repeats itself’ bears true for South Sudan. In May 1983, Kassiano, then promoted to major, led the Sudan Army assault against the Bor mutineers commanded by the same Kerbino, who had by then also been promoted to the rank of major. Facing defeat, Kerbino and his mutineers withdrew to the bush to form the nucleus of the SPLA – and the rest is history.

The second key theme of the book is about how Israeli military support helped transform the Anyanya into a more effective combat force. Magaya elaborates on how this support resulted in upgrades in weapons, and tactics, and improvement in the capacities of the Anyanya officer corps through rigorous retraining exercises both in Southern Sudan and abroad.

The literature on Israeli support for the Anyanya is still relatively thin and Magaya’s book is a welcome augmentation to the existing body of work. But on this topic, Magaya differs from his South Sudanese compatriots who have written on the issue, by giving a face to the Israeli support when he names the Israeli liaison agent on the ground in South Sudan. He has also produced photographs of this agent and takes time to elaborate on the work the Israeli officer did to bolster the Anyanya forces.

Magaya also focuses on the often-missed impact of Israeli military support in unifying the disparate and various Anyanya units under one central command led by Joseph Lagu. However, Magaya treats this support as an end in itself and displays surprising naiveté by not recognising Lagu and Gordon Muortat’s groundwork in soliciting this support.

Magaya’s main sin in this book is failing to situate the Western Equatoria Anyanya story within a context that has depth and perspective. He is mostly descriptive, rather than analytical in his elaboration of events.

He writes like a person who is not even aware of works on the Anyanya by his contemporaries and therefore fails to see areas that require more detail, the gaps that should have been filled. One missed opportunity is a detailed discussion on the personality of Fr. Saturnino Lohure, and his activities in the Congo in the lead-up to the launch of military activities in South Sudan.

Published in the spring, the book would have benefited from a competent editor to help develop concepts, eliminate vagueness and some inaccuracies, as well as polish language. But overall, it is a useful account by a key player of the Anyanya in Western Equatoria.

Following the Addis Ababa Agreement of 1972, Magaya was absorbed into the Sudan Armed Forces with the rank of major. He has since held several high profile military and government positions. Most recently he was minister of interior in South Sudan and is currently serving as ambassador to the European Union.

Despite the book’s shortcomings, Magaya must be commended for taking the time to write it. Many of the remaining Anyanya leaders are aging and dying. Hopefully, this book will inspire them to record their accounts in the jurisdictions they served for posterity.

Brian Adeba is an Associate of the Security Governance Group in Canada. Reach him on Twitter @kalamashaka