President Sassou Nguesso prepares for final stage of his constitutional coup: elections in the Republic of Congo

The people may want change, but the government has made sure they won’t get it at the ballot box on 20 March.

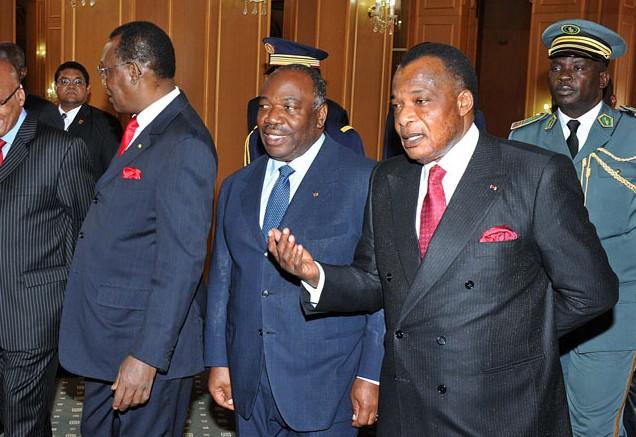

President Denis Sassou Nguesso (right) will almost certainly extend his rule after Sunday’s elections. Credit: GCIS.

When citizens of the Republic of Congo are called to the polls to elect the country’s next president on 20 March, turnout is likely to be low since most believe the results are foreordained.

President Denis Sassou Nguesso has ruled the Republic of Congo for all but five years since 1979, and is poised to extend his reign for at least another five. After seizing power in a 1979 coup, he ruled as a military dictator throughout the 1980s. Swept up in the “Third Wave of Democracy” that hit Africa as the Berlin Wall fell, Sassou Nguesso momentarily lost power in 1992 elections, but he reclaimed it following a brutal civil war in 1997 and has claimed victory in two fraudulent presidential elections since.

The 2016 presidential election was supposed to be different. Drafted by Sassou Nguesso’s personal lawyers in 2002, the constitution limits presidential terms to two and requires that candidates be no older than 70 years of age at the time of inauguration. Sassou Nguesso is now 73 and approaching the end of his second term.

In order to retain power beyond 2016 and maintain a veneer of legitimacy – however thin – Sassou Nguesso had to engineer a constitutional referendum.

“Preparing the ground”

The government advertised the constitutional referendum held in October 2015 as an act of democracy – an effort, in the words of the president, “to give voice directly to the people”. But in reality, the regime began its efforts to engineer the revision – “preparing the ground” as Congolese citizens describe it – in 2011, just two years after Sassou Nguesso won re-election previously.

This effort featured two components. First, the carrot. The regime signaled it would concede some amount of executive power in exchange for a third presidential term. This approach was undertaken by Sassou Nguesso’s longtime aides, chief among them Jean Claude Ibovi, in the pages of Brazzaville newspapers. The country requires a strong executive in the post-civil war period, the president’s champions argued, but conceded that its maturing democracy also needs a “real separation of powers between the executive and the legislature, so that ministers are responsible before parliament and not before the President of the Republic”. The regime also proposed reducing presidential terms from seven years to five.

Coupled with this carrot came the stick. If the opposition rejected the bargain, the regime made it clear that it was willing to employ violence. The strongest signal came in April 2013 with the launch of “Operation Smack of the Elders”. Between April and July, the government deported as many as 250,000 citizens of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), often brutally. The government justified the operation with appeals to the crime rate, but the political opposition interpreted the violent campaign as a “show of force”.

Shortly thereafter, the regime moved against the press. After Elie Smith, a Cameroonian journalist who served as the lead anchor for Maurice Nguesso’s television station, announced his opposition to a constitutional referendum, he and his family were assaulted and deported. Sadio Morel Kanté, a Congolese citizen born to West African parents who reported the assault, was herself abused and deported to Mali. As many as ten other independent newspapers were forced to close. Meanwhile, once regarded as the “old gray lady” of Central Africa, La Semaine Africaine was pressured into adopting an obviously pro-regime editorial line.

The prospect of a constitutional referendum dominated Congolese political debate through late 2015. Sassou Nguesso, for his part, consistently refused to comment: “That is not the issue of the day,” he repeated when asked by the press corps. He sought to cultivate the appearance of disinterest, though few were fooled.

However, the president’s studied disinterest did buy him some time. After witnessing the Arab Spring in 2011 and the Burkinabé Revolution of October 2014, Sassou Nguesso was keenly aware that moments of popular frustration can easily coalesce into mass protests. By demurring for a time, Sassou Nguesso kept his options open; he could proceed with the referendum or, if Brazzaville’s political climate grew tense, change tack and anoint his son as his successor.

The referendum

On 22 September, Sassou Nguesso finally committed to the referendum. The timing of his announcement was strategic. It occurred just three days after the 11th African Games, held in Brazzaville, and after it had become clear that both President Pierre Nkurunziza of Burundi and President Paul Kagame of Rwanda would brave international condemnation to secure third presidential terms as well. Indeed, Sassou Nguesso and Kagame moved forward in tandem.

Having committed himself to the vote, Sassou Nguesso moved quickly. The referendum was scheduled just five weeks later for 25 October. Congolese citizens responded angrily. On 27 September, only five days after the announcement, opposition leaders organised a protest of some 30,000 people, easily the largest since Sassou Nguesso’s return to power in 1997 and possibly larger than those that forced him to convene the National Conference in 1991 which had led to the elections a year later.

However, rather than suppressing protesters, Sassou Nguesso organised a “mega concert”, though it was ultimately boycotted even by headliner Roga Roga. Congo’s pro-democracy activists continued to coordinate via social media, and days later the hashtag #SassouFit emerged as the rallying cry, a clever phonetic play on ça suffit (“that’s enough”).

The opposition held a series of mass protests over the subsequent weeks, drawing thousands, and now, the regime responded brutally. One Pointe-Noire protest yielded more than 30 deaths, while the regime shut down SMS text messaging, limited internet access, and placed several opposition leaders under house arrest.

As repression intensified, the Congolese diaspora sought to attract international condemnation, hoping that Western governments would force Sassou Nguesso to abandon the “constitutional coup d’état”. On 20 October, protesters blocked traffic at the Arc de Triomphe in Paris during the evening commute and called upon the country’s former colonial master France to “assume its responsibilities”.

Less than a year earlier as the Burkinabé Revolution unfolded, French President François Hollande had proclaimed: “Wherever constitutional rules are abused, wherever freedom is violated, wherever democratic transitions of power are prevented, I declare here and now that citizens will always find in the Francophone world the support necessary to ensure that justice, rights, and democracy prevail.”

But by 21 October 2015, Hollande had radically changed his tone, saying: “In Congo, President Sassou Nguesso may consult his people. This is among his rights and the people must respond. Then, once the people have been consulted – and this goes for all heads of state around the planet – we must always be careful to unite, to respect, and to make peace.”

Sassou Nguesso’s propagandistic newspaper, Les Dépêches de Brazzaville, trumpeted Hollande’s announcement with an enthusiasm usually reserved for the president himself. Congolese citizens declared it a “knife to the back”. “By prostrating himself before Sassou Nguesso, François Hollande has weakened the word and the moral authority of France,” said one activist. Meanwhile, even French daily Le Monde, normally friendly to Hollande’s Socialist government, led with the headline “the African press denounces the complicit support of François Hollande to President Sassou Nguesso”. The outcry was so great that, on 22 October, the Élysée Palace issued a press release to reaffirm his previous proclamation of 2014.

Despite that slight reversal, for most Congolese citizens, this marked a moment of resignation, while for the government it was a moment of triumph. The referendum was held and, days later, it claimed that some 73% of eligible voters participated , with 92% endorsing the new constitution. In reality, most Brazzaville polling stations were deserted until late afternoon, when the regime began bussing in its few supporters – many of whom had reportedly been paid for their votes – to create the illusion of participation. The opposition had called for a boycott and the majority of Congolese citizens heeded the call.

Since reclaiming power in 1997, Sassou Nguesso has quietly accumulated one of the continent’s worst human rights records. As well as helping him extend his rule, the new constitution will prove useful in this regard too. In addition to forbidding extradition of Congolese citizens, the new constitution grants presidents lifetime immunity from prosecution. It even specifies the charge for transgressing these provisions: treason.

Hope for change?

With most Congolese citizens resigned to a Sassou Nguesso victory, the electoral campaign has proven far less turbulent than the referendum. Nevertheless, it currently features nine candidates: Sassou Nguesso, three candidates who comprise the “moderate opposition” and are likely funded by the regime, and five candidates who comprise the “radical opposition”.

The five “radical opposition” candidates claim membership in IDC-FROCAD, an umbrella alliance that organised the referendum boycott. Of these five, three – Guy Brice Parfait Kolélas, Claudine Munari, and André Okombi Salissa – have served as Sassou Nguesso ministers for a collective 29 years since 1997 and only resigned after the president chose to pursue the constitutional referendum. Regarded as “collaborators”, most Congolese citizens view the three with distrust, unworthy of their hopes for a better future.

The two other “radical opposition” candidates are General Jean-Marie Michel Mokoko and Pascal Tsaty Mabiala. The latter has served as secretary-general of the opposition UPADS since 2006. Political heir to Pascal Lissouba, the only freely-elected president in Congo’s history, Tsaty Mabiala draws modest support from the southern regions of Niari, Bouenza, and Lékoumou but scant support elsewhere.

This leaves General Mokoko as Sassou Nguesso’s most credible opponent, and the one around whom the other candidates will coalesce if a unique “radical opposition” candidate emerges in the campaign’s final days. Mokoko remains among Congo’s few icons, one of the only national political figures whose reputation is largely unstained. Military chief-of-staff during the National Conference of 1991, General Mokoko ordered the military to protect the Conference’s sovereignty despite Sassou Nguesso’s orders to disband it. For this, he is regarded as a pivotal figure in Congo’s democratic transition of the early 1990s.

A native of Plateaux region in northern Congo, General Mokoko is also the only candidate who can credibly attract disaffected northerners – who would otherwise support Sassou Nguesso – and longstanding regime opponents in the south. Sassou Nguesso knows this, and in recent weeks General Mokoko has repeatedly been threatened with incarceration.

The 20 March election will be neither free nor fair. The “independent” electoral commission is filled with long-time Sassou Nguesso allies. On 26 February, the government refused entry to the head of the Amnesty International delegation, and there will be no election monitors from credible international organisations. And so, whatever the actual vote, Sassou Nguesso will claim victory, likely with around 80% of the vote and a turnout rate of 65%-75%.

Rather than through elections, Congolese citizens’ best hope for democratic change is a Burkinabé style revolution in which massive protests drove long-standing President Blaise Compaoré from power, with Mokoko the consensus choice afterwards. The regime knows this, and so the opposition will have to coordinate mass protests without the benefit of surprise, a factor that so often proves crucial to a revolution’s success. The majority of Congolese citizens want political change. But as things stand, it seems almost certain they will be deprived of it for at least another five years.

Thanks Brett for this enlightening but thoroughly depressing update. I am especially saddened to see DSN’s regime returning to its old trick of deportation as a means of muzzling dissent.

Palmbomen in het algemeen, en uiteraard alsmede de Fortunei, houden van daglicht.

Het is dus essentieel een fijn zonnig plekje te bepalen voor de palmboom,

graag zowel dat de palm niet op de tocht staat.

Also visit my website – http://Gpeus.Com/Uncategorized/With-That-Said-Though-He-Seems-And-It-Has-Shown-Time-Time

Besproei de palmboom wekelijks met vocht, tijdens de lente/herfst en de avonden van de zomers.Besproei de palm elke week met vocht,

in de lente/herfst plus de avonden van de zomers.

Look at my web site: Winterharde Palmbomen

De Trachycarpus fortunei is een palmbomensoort.

De Fortunei is de uiterst populaire palmboom die Erkend is in ons koude Nederland.

De Trachycarpus fortunei is het allerwinterhardst,

vandaar!

My blog … Teeninga Palmen

Er zijn veel soorten planten, en vandaag hebben wij het over de Trachycarpus fortunei.

Deze soort plant is een palmboom, een tropische soort dus.

De Trachycarpus fortunei is de bijzonder gewilde palmensoort die de

onze vorst kan dragen.

My page: ttlink.com

Onder de palmbomensoorten, vindt u de Trachycarpus fortunei.

De Fortunei is de meest populaire palmboom welke beroemd is voor ons koude

Nederland. Dat komt doordat de Trachycarpus

fortunei het allermeest winterverdragend is.

Look at my site: Linette