How Zambia’s once insuperable MMD returned to power by disappearing

Despite dominating Zambian politics for 20 years, the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy was all but wiped out in last year’s legislative elections. But it’s former leaders were not.

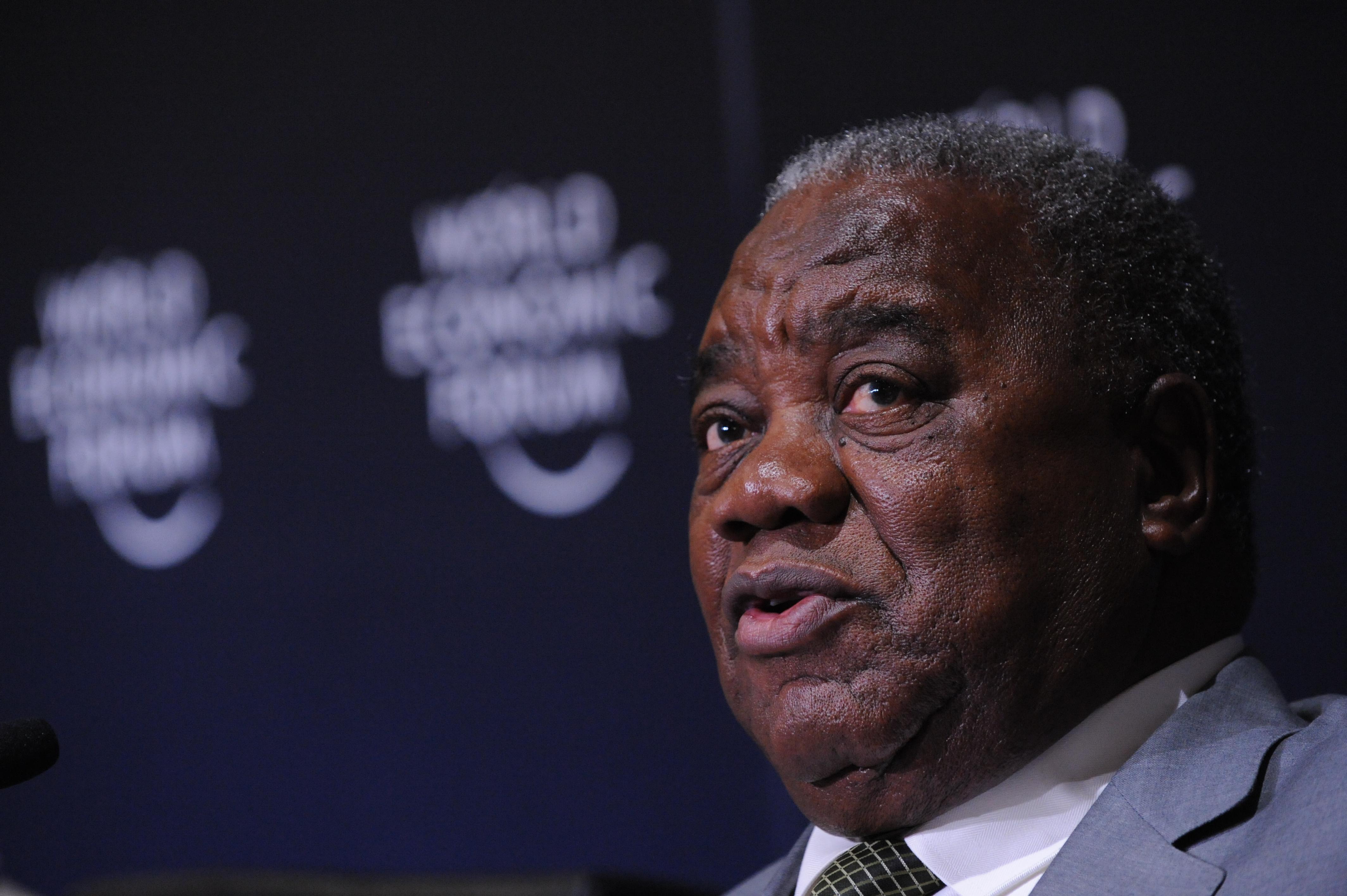

Former president Rupiah Banda (pictured) has become an ever more influential ally of President Lungu. Credit: Zahur Ramji / Mediapix.

In Zambia’s hotly contested elections in August 2016, one might be forgiven for thinking there were only two political parties vying for power.

After all, the campaign was dominated by the ruling Patriotic Front (PF), led by President Edgar Lungu, and the opposition United Party for National Development (UPND) under Hakainde Hichilema. Together, the two parties secured 98% of the presidential votes and 138 of the 156 seats in the National Assembly, with the PF and Lungu narrowly coming out on top.

However, at the ballot box, voters were also presented with a handful of other candidates and a dozen other political parties – among them, the once insuperable Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD).

From 1991 until 2011, the MMD completely dominated Zambian politics. Under Frederick Chiluba from 1991 to 2001, the country essentially operated as a one-party state. And after he stepped down, the MMD won three more elections under two further presidents, Levy Mwanawasa and Rupiah Banda.

In 2011, the MMD’s two-decade rule finally came to an end, but it remained the country’s main opposition. At this point, one might have expected the former ruling party to regroup and challenge strongly in 2016. But instead, it scraped just 2.7% of the vote and lost over 50 seats in the National Assembly. It didn’t even put forward a presidential candidate.

A challenger emerges

The story of MMD’s decline starts in 2001 when President Chiluba’s two terms in office came to an end. In the fraught process to choose a successor that followed, Mwanawasa emerged as the new presidential candidate. But this led the frustrated Michael Sata, a long-standing MMD minister and national organising secretary, to storm out of the party and set up the rival PF.

Although the new party struggled in 2001, it grew as the charismatic Sata attracted supporters with his pro-poor populist rhetoric. More MMD members – particularly its northern Bemba-speaking bloc – defected to the PF, and in 2006 elections, the party came second, becoming the main opposition.

In 2011, the PF did one better. Thanks to a strong showing in urban areas and Bemba-speaking provinces in northern Zambia, Sata was elected president. The PF became the biggest party in the 158-member parliament, though with just 60 seats, it only had five more than the MMD and was short of a majority.

The PF therefore embarked on a strategy to extend its advantage. Firstly, it lured opposition politicians to defect with the promise of automatic membership and deputy ministerial positions. Secondly, it petitioned the courts to annul and re-run certain 2011 legislative elections, alleging corruption.

These tactics were successful. By the end of 2015, Zambia had held a plentiful 35 by-elections, 26 of which were triggered by the nullification of results or defections. In these re-runs, the PF won 23 more seats, giving the ruling party a clear majority in parliament and slashing the MMD’s numbers to below 40.

A new alliance

The opposition MMD was a waning force, but perhaps ironically, it was the sudden death of President Sata in October 2014 that set the stage for its broader demise. Under Zambia’s then constitution, the country was required to hold a presidential by-election within 90 days, and this plunged both the PF and MMD into bitter internal contests over who should be their party’s nominee.

In the ruling PF, Edgar Lungu secured the candidacy at the expense of a rival faction that included then Acting President Guy Scott. In the MMD, the contest hinged on a legal battle that eventually saw Nevers Mumba emerge as the presidential candidate over former president Rupiah Banda.

In the ensuing acrimonious, competitive, and fluid political environment, an unlikely alliance was forged.

On one side, PF candidate Lungu had been denied access to state resources by Acting President Scott, who insisted they should not be used for partisan campaigns, and was looking weak in certain regions. On the other, the defeated Banda was reportedly now looking to ally himself with a candidate who, if successful, would drop corruption charges, initiated under Sata, that related to his time as president.

In each other, the two found what they were looking for. Lungu reportedly made promises to Banda. And Banda drew on his popularity in the Eastern Province, where the PF was particularly weak, and procured considerable funds for the campaign.

The MMD was torn three ways. Some switched to campaigning for the PF like Banda. Others supported the increasingly popular UPND. And only a small contingent remained loyal to Mumba. In the end, the MMD came fourth with a dismal 0.87%. Lungu won with 48.3%, narrowly defeating the UPND’s Hichilema on 46.7%.

The real power

With the PF’s narrow victory in 2015 and again in August 2016, the partnership between Lungu and the ever more influential Banda was cemented. Since then, charges against Banda have been dropped and several more MMD members have been incorporated into the ruling party.

Dora Siliya, a Banda ally from the Eastern Province, defected and was given a ministerial position in 2015 despite still facing criminal charges. Lucky Mulusa, a well-known former MMD politician, became an aide to Lungu. And Felix Mutati was appointed Finance Minister this September.

In all, six key ministers in Lungu’s current cabinet are formerly of the MMD. The party itself has been hollowed out, but with President Lungu so reliant on Banda for his electoral victories, many of its former stalwarts have found themselves in powerful positions.

One effect of absorbing these figures into his government is that Lungu has reduced his dependence on the so-called Bemba faction of his party. Many of these longer-standing PF members – sometimes described as the “true green” in reference to the party colour – are angry at Banda’s new influence and at being side-lined.

These frustrations led two high-profile Bemba members – Miles Sampa and Mulenga Sata –to campaign against the PF in the recent elections. Meanwhile, in November 2016, Lungu courted controversy when he dismissed Chishimba Kambwili, another prominent PF member, from his position as Information Minister.

In Zambia’s political culture, parties tend not to be divided along ideology. Membership is fluid and based on self-interest. This has enabled MMD elites to cross over to the ruling party without losing their popular support, and means that while the party may have all but disappeared, many of its former leaders – most notably Banda – remain close to power.

We will have to wait and see how these alliances and party reconfigurations continue to shift through Lungu’s first full term, especially as the frustrated “true green” faction and former PF elites consider their next move.

Zenobia Ismail is a PhD candidate in the Department of Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge. Previously she was a manager for the Afrobarometer research network based at Idasa, South Africa.

Firstly correct me if I am wrong but the two miles sampa and mulenga sata came back and apologised and found the party structures could not allow them to get back and having lost there parliamentary seats could not be selected for ministerial positions (and mulenga sata was a nominated mp) and over and above they really were not as high profile as you have depicted them.

Secondly you have made PF appear to be a tribalistic party for Bembas’ which is on the contrary. Even the voting showed that in the Bemba province’s unlike the upnd’s HH party which is trablistic and votes for there own tribes man all the time. Actually even this behaviour of the upnd could have allowed for Banda and Lungu to forge this alliance which you speak of. If you check the previous elections in the hh upnd has never lost any seat in there provinces and the talled votes show there tribalism This has influenced candidates from other tribes to try to do the same.

Finally in as much as there can be truth in what the writer has brought out but my personal opinion is the writer should research some two three ayouta more.