Droughts in East Africa becoming more frequent, more devastating

Can the cycle be broken?

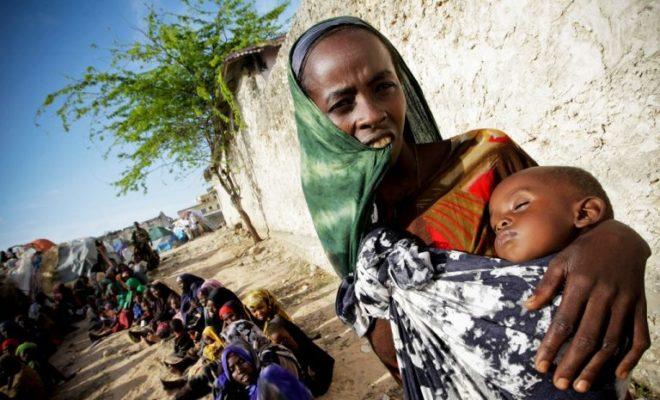

Somalia declared a famine in 2011 and is facing severe warnings again. Credit: Photo/Stuart Price.

If the current drought in the East Africa brings a sense of déjà vu, it’s because we’ve been here before – several times.

This is a region where the global forces of climate change, forced migration, and volatile food supply converge, resulting in severe hunger and, at worst, famine. However, while drought is not new, it has become increasingly frequent.

As the UN’s International Fund for Agricultural Development notes: “From 2005, 2006, 2008, 2011, 2015, 2016 and now 2017, datelines change but the stories of unimaginable hardship, death and depravation remain largely the same.”

As with the frequency, the severity has also intensified. The 2011 East African drought was reportedly the region’s worst for 60 years. But while that crisis affected over 12 million people, today’s has already left an estimated 12.8 million severely food insecure. And things are expected to worsen in the coming months with low rainfall forecast from March to May.

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), today’s situation is so widespread because three consecutive years of diminished food production has exhausted people’s capacity to cope with another shock, while access constraints, rising refugee numbers and outbreaks of communicable diseases in the greater region add to the pressures.

Conflict is another key factor as both a driver and result of the drought. It is no coincidence that it is in South Sudan and Somalia – where conflict has led to millions of displacements, made it harder to cultivate land and hampered humanitarian access – that people are in most danger.

This February, South Sudan, which has been at war since 2013, became the first country in six years to declare a famine. UN agencies say 100,000 people there are on the verge of starvation and almost 5 million – more than 40% of the country’s population – are in need of urgent assistance. In Somalia, where 258,000 people died in the world’s previous famine in 2011, further starvation looks like a distinct possibility again.

At the same time, drought has also aggravated existing tensions in places such as the Rift Valley in Kenya where increasingly scarce resources has led to growing violence between pastoralists and farmers.

Response efforts

Given the critical situation, the governments of the countries most affected have sounded the alarm.

In February, the Kenyan government declared the drought a national disaster and committed nearly half of the $208 million for which UNOCHA appealed to assist response efforts in the country.

In Ethiopia, the government and its humanitarian partners launched the 2017 Humanitarian Requirements Document (HRD) this January, looking for $948 million to help 5.6 million people with emergency food and non-food assistance. The government itself committed $47 million as a first instalment.

In South Sudan, the declaration of famine brought greater global attention and pledges of financial assistance for the country’s deepening crisis. Despite ongoing conflict, the government promised “unimpeded access” to all aid organisations, though was widely criticised for increasing the cost of foreign worker permits from $100 to $10,000 just days after the declaration.

Finally, in Somalia, UNOCHA launched a $864 million humanitarian response plan. With finances scare, however, the government itself has struggled raise funds. Even Somaliland’s own National Drought Committee has only been able to contribute $7 million.

Regionally, the East African bloc known as the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) has been at the forefront of addressing the drought, coordinating response efforts through its Drought Disaster Resilience and Sustainability Initiative (IDDRSI).

Meanwhile internationally, UNOCHA issued a Call to Action for the Horn of Africa this February, appealing to the international donor community to avail $1.9 billion needed to respond to the unfolding crisis. The UK has pledged to give South Sudan and Somalia aid packages of £100 million ($120 million) each, while the US contributed nearly $855 million to support relief interventions in the Horn of Africa in 2016 and has committed nearly $182 million for critical relief interventions so far in 2017.

Prepare for the worst

Today’s crisis is the result of myriad factors, and mitigating this and future disasters will take concerted action at all levels, from civil society to governments and international organisations, and from the local up to the national, regional and international.

At a national level, certain governments – particular Kenya and Ethiopia – have shown decisive leadership in their actions over the past year. But although some early warning systems and methods have improved since the 2011 crisis, preparedness, coordination and response mechanisms need to be developed much further. To this end, regional organisations such as IGAD and the East African Community must be financially and technically capacitated to allow for flexible, quick and robust responses when drought inevitably strikes again.

It also bears repeating that states must develop effective policies to move beyond rain-fed agriculture, adopt policies of reforestation, and support farmers in transforming agriculture from subsistence to commercial farming in order to ensure food security.

Meanwhile internationally, climate change cannot be ignored. As a region, East Africa has contributed a miniscule fraction of the greenhouse gasses that have been emitted, yet it bears an enormous burden from the man-made problem. The 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change was a significant milestone in tackling climate change, but much work needs to be done to ensure the promises made are implemented and upheld.

Finally, the centrality of conflict to the current crises bears repeating. East Africa has become an epicentre of an array of dynamics, from global climate change to conflict, all of which combine to create catastrophes affecting millions of people. We have been here before and we will be here again. The question is whether, and how quickly, we will learn from our past mistakes in identifying the roots of the crises, tackling the underlying problems, while preparing for the worst.

Stephen Wainaina is a humanitarian trainee at a leading international NGO in Nairobi, Kenya. Follow him on twitter at @SteveNjugz.

The climate change effects are devastating, soon there will be no drinking water

Hello. And Bye.