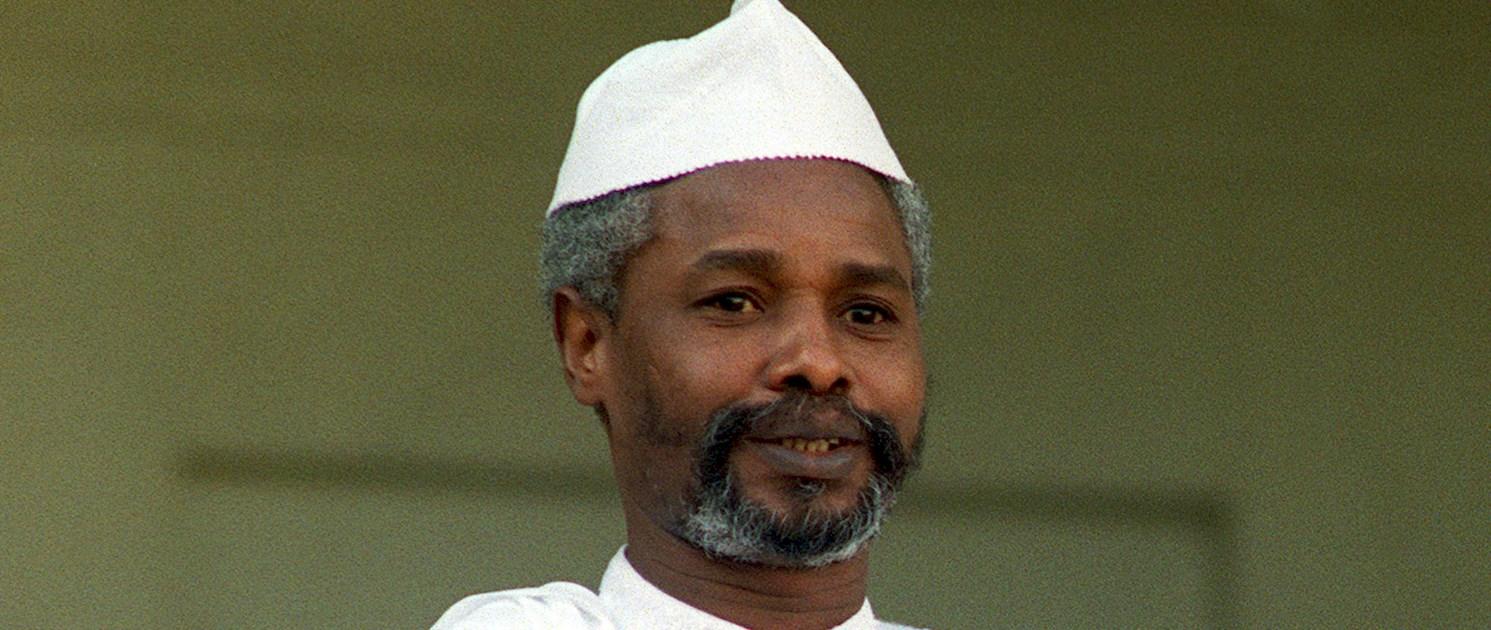

The Habré trial: The future for African justice?

The trial of Chad’s former president is finally over, but its significance for Africa may have just begun.

Hissène Habré’s life sentence was upheld last week, bringing his long trial to an end.

The decision by the Appeals Chamber of the Extraordinary African Chambers (EAC) to uphold Hissène Habré’s life sentence for war crimes, crimes against humanity and torture is the final step in a 25-year campaign for justice by his victims.

The appeal, which was launched by the former Chadian president’s court-appointed defence team bizarrely without his consent, had questioned a number of technical points of his trial, including the competence and experience of one of the judges. It was roundly rejected by the court, which confirmed Habré’s sentence once and for all.

“I have been fighting for this day since I walked out of prison more than 26 years ago,” said Souleymane Guengueng, one of the leaders of the victims’ justice groups, following the verdict.

Habré now looks likely to spend the rest of his life at Cap Manuel prison in Dakar, barring a presidential pardon from Senegal’s Macky Sall or an offer from another African country to allow him to serve out the rest of his sentence there.

Habré was previously jailed in May 2016 after a ten-month trial in which over 90 victims and witnesses testified about horrific crimes carried out by his secret police – the DDS (Directorate of Documentation and Security) – during his eight-year rule from 1982-90. The court heard graphic accounts of punishments such as arbatachar (‘14’ in Arabic) whereby prisoners had their hands and feet tied together behind their backs or car exhaust pipes inserted into their mouths, as well as testimony of mass executions, sexual violence and the burning of entire villages.

Although the Appeals Chamber overturned the former president’s conviction for the direct commission of rape against one woman, the court concluded that his overall conviction on the basis of command responsibility – that as president and chief of the army he knew or ought to have known what his subordinates were doing – should remain intact.

A model for the future?

The Habré trial was a landmark case in that it was the first time the courts of one African country have been used to try the former leader of another. The experimental EAC was a ‘hybrid’ court blending international and national justice systems. It was established within the Senegalese courts by the African Union (AU) in 2013 after a long and relentless campaign by victims groups, which involved failed bids to prosecute Habré in Senegal (where he had fled in exile in 1990) and Belgium.

The EAC has been formally disbanded following the trial, but the case has opened up fascinating possibilities for future trials in Africa. Given its generally satisfactory conclusion – and with a growing backlash in some countries against the International Criminal Court (ICC) – many have speculated that the EAC could be a template going forwards. The model is additionally attractive in that it cost around $9 million, which is “twelve times cheaper than a trial at the ICC” according to journalist Thierry Cruvellier who has written extensively about international justice.

The EAC approach is already being emulated in some areas. In February 2017, for example, it was announced that a chief prosecutor has been appointed for the Special Court for crimes in the Central African Republic which will be of a similar hybrid nature to the EAC.

“That it happened at all is a major step forward for hybrid tribunals,” says Kim Thuy Seelinger from the Director of the Sexual Violence Program at the Human Rights Center, University of California Berkeley, School of Law, who assisted Habré’s victims. “It gives us an idea of what future regional hybrids, or so-called one-off ‘pop-up trials’ might look like”.

Political will

The Habré case also has its critics, however, especially those who believe the threat of prosecution may encourage leaders to hang on to power. The threat by Gambia’s new incoming government to prosecute Yahya Jammeh in late-2016, for instance, is thought to have been one of the reasons he suddenly rescinded his offer to step down peacefully.

The EAC has also made slow progress on enforcing its award of approximately €81 million ($88 million) in compensation to over 4,000 victims of torture and family members who lost loved ones. An investigation to uncover money stolen from the Chadian treasury when Habré fled into exile in December 1990 has so far found little, and a Trust Fund for the victims designed to invite contributions from donor countries has only just been established after months of delays.

Moreover, there are doubts that sufficient continent-wide political will to create similar tribunals exists. “For those who have been involved in the EAC, there is a sense that it should be continued, but there are doubts about how far the AU would go in the future in supporting another such body,” says Seelinger.

Indeed, the AU has been notably silent on the court’s outcomes. The EAC controversially relied on the principle of universal jurisdiction – the so-called “Pinochet clause” – which allows the courts of one country to indict foreign nationals for crimes committed in another country. This is a legal concept which the African Union has been critical of since the case of a Rwandan general who was briefly arrested in London on an arrest warrant issued by a Spanish judge. It remains to be seen to what extent the AU will want to invoke its use in any possible future trial.

It should also be noted that when it comes to high-level offenders, Habré was a relatively low-hanging fruit, having been out of power for more than 20 years. He was isolated and had few allies on the continent beyond Senegal’s former president Abdoulaye Wade who was beaten in a presidential election by Macky Sall in 2012.

Without Sall’s decision to push forward on the prosecution, which appeared motivated by stinging criticism of Senegal’s handling of the Habré case by the International Court of Justice, it is unclear whether it would have happened at all.

Despite some optimism, the Habré trial’s future significance is contingent on a variety of factors and remains to be seen. But for the thousands of survivors of the former president’s crimes, the fact that justice has been served and that the case is now over is significance enough.

“Today, I finally feel free,” says Guengueng.