The WhatsApp rumours that infused Sierra Leone’s tight election

Several fake news stories started online, but soon spread far and wide offline, duping even senior officials.

In Sierra Leone’s 2018 elections, opposition leader Julius Maada Bio won a narrow victory. Credit: Direct Relief.

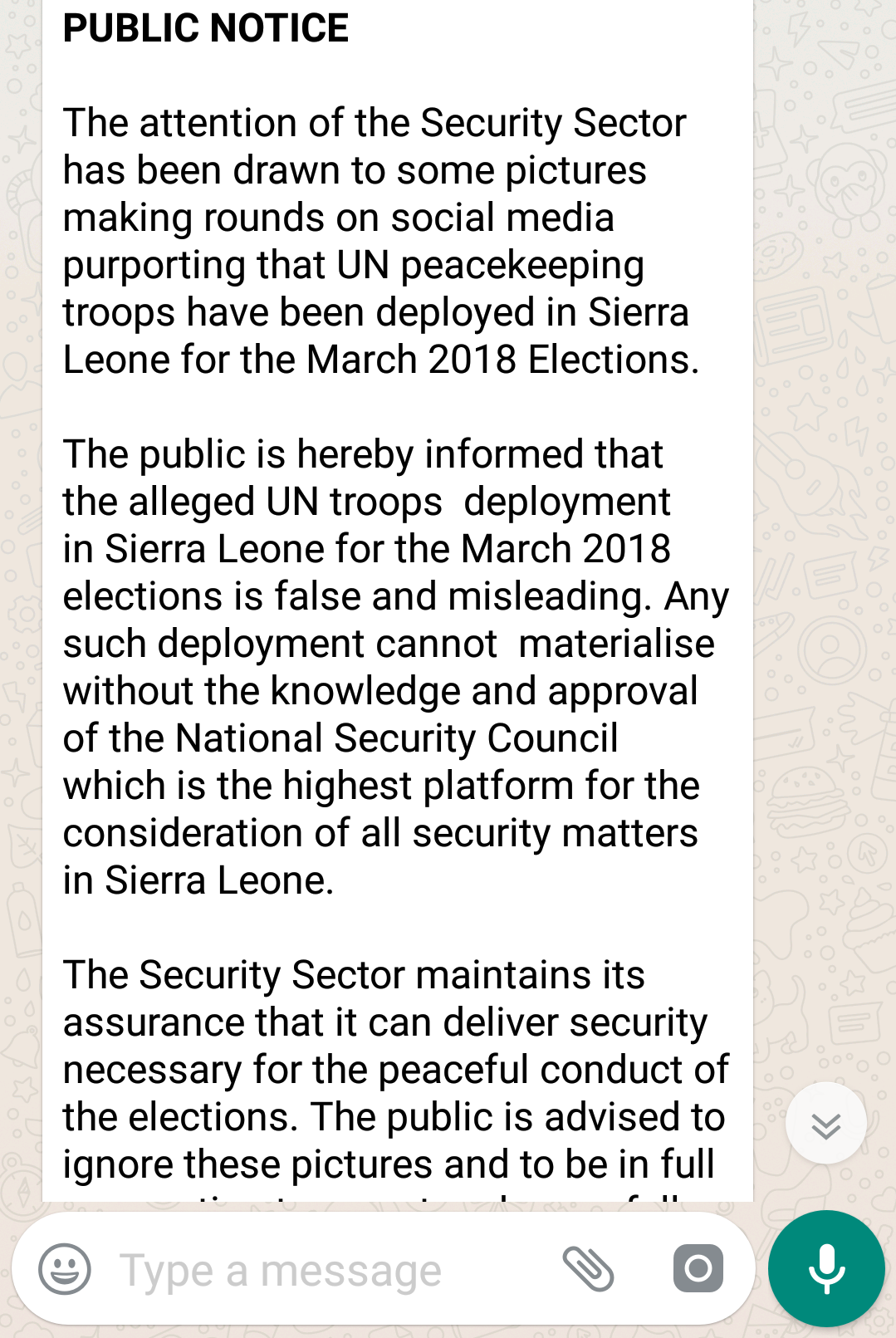

In early March, a few days before Sierra Leoneans went to the polls, news emerged that UN peacekeepers were about to be deployed. As voters geared up for the first-round of what some feared would be fractious elections, this rumour, accompanied by some very out-dated photos, spread rapidly across Whatsapp, the dominant social media platform in the country.

The story was completely false. But it continued to circulate, forcing the Inspector General of Police to issue a formal press release denying the presence of foreign peacekeepers on Sierra Leonean soil.

“Fake news” such as this was an enduring feature of Sierra Leone’s recently-concluded elections. This may have been somewhat unexpected. Particularly outside urban centres, the country’s smartphone penetration is poor, network coverage is limited, and literacy levels are low. A BBC Media Action survey in 2015 found that just 2% of respondents reported using WhatsApp.

However, claims such as those by the Carter Centre, which concluded that “the role played by social media in the 2018 campaign was very limited” due to low internet penetration – the same BBC survey estimated it at 16% – are too simplistic.

In reality, rumours and propaganda reached wide audiences as messages were rapidly forwarded, or “culled”, from one WhatsApp group to another. This impact may have been disproportionately concentrated in the capital Freetown, but this is where almost 30% of the electorate cast their ballots and where results tend to be most closely contested. Moreover, given the slim margin by which the opposition’s Julius Maada Bio eventually won the presidential run-off, even a small swing could have proven decisive.

Internet usage may be relatively low, but getting online in Sierra Leone has never been easier. Basic smartphones are now available for Le300,000 ($39), while daily data packages start at Le1,500 ($0.20). WhatsApp in particular has become a key source of news for urban Sierra Leoneans, eclipsing the readership of print media and, for the younger generation, challenging even the dominance of radio.

News – whether fake or otherwise – is spreading faster and further online. However, crucially, it is not necessarily staying there. Stories that may initially circulate on social media frequently cross into the offline world. Through word of mouth, telephone conversations or calls to popular radio shows, rumours that originate on WhatsApp can reach far wider and harder-to-measure audiences.

One example of this happening occurred during the wait for the announcement of the first-round results. The National Electoral Commission (NEC) had decided to declare the tallies in regionally-weighted 25% increments. With 75% of votes reported, the leading two candidates were separated by less than 1%. Given the tightness of the race, a second round run-off appeared to be the only plausible scenario.

Nonetheless, a falsified report, containing several inaccuracies including a published date of November 2018 (over six months in the future) began to spread on WhatsApp. It claimed that the opposition SLPP’s Maada Bio had secured enough votes to win outright with 56.3%, just above the 55% threshold for victory. This report was widely shared, was cited in discussions on street corners, and even made its way into some radio and television studios. A friend in Freetown with no smartphone or access to the Internet quoted the 56.3% figure as evidence that his favoured candidate had lost.

Even senior figures from the main political parties were liable to be taken in by fake news. In the final 25% of results announced, for instance, the two leading candidates’ vote tallies were extremely close. However, a rumour soon circulated online that the parties had in fact got the identical number of votes from the final portion of votes, receiving exactly 249,000 each. Although this was not true, party officials on both sides cited this suspiciously improbable result as evidence of possible foul play by the NEC.

WhatsApp power

These episodes demonstrate how information that spreads across social media can shape national narratives. Against this background, it becomes important to know who is using these networks.

According to Andrew Lavali, Director of the Institute for Governance Reform, “the people with influence in the country all use social media. It matters less if the overall percentage of users is relatively small”.

However, in many ways, the lines between conventional and social media are simply increasingly overlapping. Popular, and influential, radio stations such as Radio Democracy have also begun to stream shows on Facebook, allowing listeners to tune in on their phones, and opening up comments to make discussions more interactive. Similarly, WhatsApp groups share screenshots of newspapers’ front pages, giving them a much wider reach than their print circulation.

This is not to overstate the impact of social media, but to recognise that its impact extends beyond its primary users and the nation’s borders. The ways in which information circulated on WhatsApp penetrates offline spaces warrants further study as does diaspora use of messenger platforms to engage in and shape political debate in the country.

Social media has the potential to provide a platform for greater political debate, improved understanding of voting processes, and more meaningful citizen-led accountability. But Sierra Leone’s polarised political environment – in which trust between the state, citizens and political parties is in short supply – provides fertile ground for the spread of falsehoods and rumours. These may start online, but they do not always stay there.

The author was in Freetown in March 2018 to examine the use of social media in Sierra Leone’s election for the University of Edinburgh’s SMS Africa Project.