Only boys allowed: Seven faces of Zimbabwe’s political patriarchy

At less than 15%, women make up a tiny fraction of candidates in the upcoming elections. Here’s how society keeps it that way.

Zimbabwe’s patriarchy takes many forms. Credit: Emmerson Mnangagwa.

In the aftermath of Zimbabwe’s last set of elections in 2013, UN Women issued a glowing statement celebrating the progress made on female political representation. Overnight, the country had jumped up the global rankings for women in parliament, going from 17% to an impressive 35%.

In Zimbabwe itself, however, women’s rights activists were more restrained. Among other things, they noted that of the 86 female MPs now in the National Assembly, only 26 had been directly elected. Very few women had actually been put forward for direct contest and won. The remaining 60 had been appointed in accordance with the constitution’s mandatory quotas.

Once in parliament, these 60 female MPs became known derogatorily as the “Bacossi MPs”, a reference to the 2008 Basic Commodities Supply Side Intervention (Baccossi) subsidies programme on basic goods that were derided as being substandard. The selection of these MPs by their parties rather than election by the people led them to be perceived as lacking a legitimate mandate. They were assumed to be incompetent and incapable of winning contests based on merit.

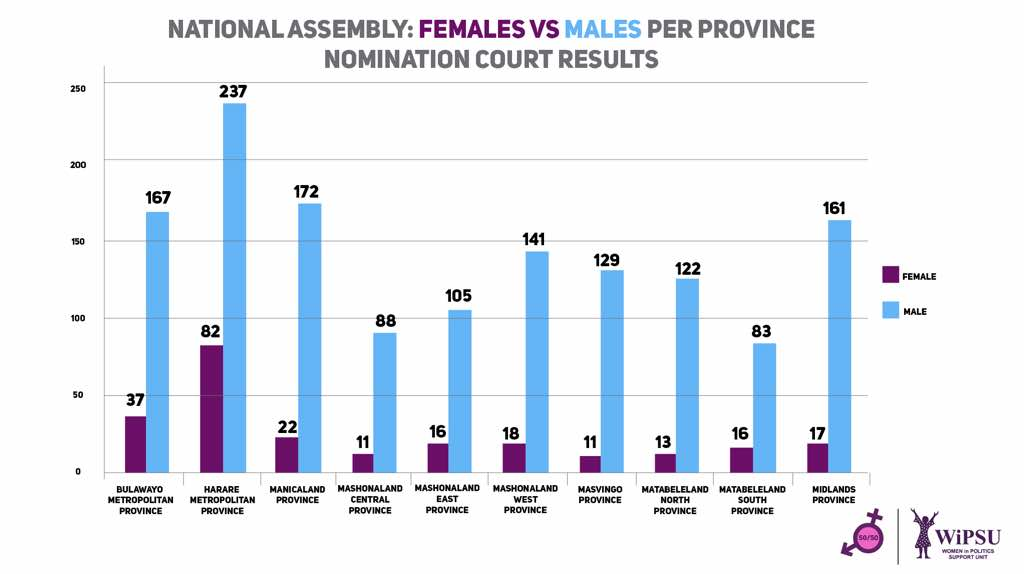

The reality behind the 2013 election’s lustre of progress was therefore always more questionable than it seemed. And now, with elections looming again, Zimbabwe’s women seem to be in an even weaker political position. According to the Women in Politics Support Unit, female nominees make up less than 15% of the candidates that will be standing for the National Assembly on 30 July 2018.

Others have noted the conspicuous absence of women in high level politics and the ongoing resilience of Zimbabwean patriarchy. But it is also worth examining some of the many ways – some more direct or subtle than others – in which this patriarchy manifests and is daily reinforced.

1) Pitting women against each other

For decades, Zimbabwe’s main political parties have pitted female politicians against one another. In 1995, the ruling ZANU-PF allegedly elevated Vivian Mwashita to go up against Margaret Dongo, a vocal human rights defender and critic of corruption within the party. In 2014, ZANU-PF used then first lady Grace Mugabe to lead a smear campaign against then vice-president Joice Mujuru, accusing her of trying to kill President Robert Mugabe and of promiscuity with top ranking officials in the party. Just this May, the main opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) is alleged to have overseen irregularities in a primary election that saw its favoured candidate Joana Mamombe push out Jessie Majome. Majome was reportedly told she was “old and should retire to the countryside to herd donkeys”.

It is telling that Zimbabwe’s parties feel the need to employ women to attack other women. It is also revealing that there is a tendency for elites to create zero-sum games between female candidates rather than simply supporting multiple qualified nominees.

2) Attacking women on their character and personal lives

In the political sphere, women face all kinds of attacks on their character and personal lives that is not the case with men. Fadzayi Mahere, a young lawyer running to be an independent MP in Mt Pleasant Constituency, for example, has been harassed and insulted for being single. Former MP Priscilla Misihairabwi-Mushonga was labelled a “bra-burning feminist” and effectively accused of murdering her husband, an experience that contributed to her suffering from depression. Earlier this year, the opposition figure Thokozani Khupe was called a prostitute and physically attacked after questioning the legitimacy of the MDC’s political transition following the death of leader Morgan Tsvangirai.

Although male politicians are also criticised, the special kinds of extreme and personal attacks that are reserved for women reveal the sexism that is deeply entrenched in Zimbabwean society.

3) Dismissive stereotyping

As is the case in much of the world, Zimbabwe’s female politicians are denigrated for displaying the same qualities that may be admired in men. Rather than being treated in the same way as their male counterparts, women are dismissively stereotyped in ways that seek to control their actions. Assertive women, for example, are aggressive (ane hukasha). Quiet women are docile (imbodza). Women who are considered good-looking are sluts (ihure iri); those who are not are slobs (imbuya dzekupi idzi).

4) Creating standards that don’t exist for men

Zimbabwe does not have parliamentary term limits, yet with Jessie Majome reaching the end of her second term as Harare West’s MP, many people are claiming it is time for her to step down lest she overstay her welcome. While there is some merit to the argument that a turnover could bring new and progressive ideas, this argument is not being made in reference to any of the male politicians who have served much longer than she has – among them MDC leader Nelson Chamisa (an MP since 2003) and ZANU-PF Obert Mpofu (an MP since 1987). Majome’s cases serves as a classic example of standards being created for women that do not exist for men.

5) Talking the talk of gender issues, but not walking the walk

Zimbabwe’s politicians all try to mobilise women’s vote during elections. They know that they would lose without it since women make up 52% of registered voters. Yet, once in parliament, male MPs have consistently dismissed the efforts of their female colleagues to raise and discuss women’s issues. Typically, male politicians who utilise the rhetoric of gender equality in election periods drop it along with any genuine attempts to take action once voted in. This may create the veneer of progress, but the reality below the surface remains the same.

6) Assuming women’s causes are frivolous while men’s are serious

In Zimbabwean politics, men’s intelligence and political competence is usually assumed, while women’s has to be proved. The media plays into this narrative by often painting female MPs who speak out on women’s issues as shrill feminists obsessed with furthering frivolous agendas such as access to and affordability of sanitary wear and the criminalisation of new acts of violence against women such as revenge porn. Men, by contrast, are portrayed as being astute and engaged on issues of “public importance” such as economic recovery.

7) Allowing sexist remarks

Men in Zimbabwe are able to make openly sexist comments with relative impunity. Former president Robert Mugabe declared in the past that women will never be equal to men, while opposition leader Nelson Chamisa recently claimed, in what he would later dismiss as a joke, that he would give his 18-year-old sister to President Emmerson Mnangagwa if the latter won the elections. These misogynistic statements were condemned in some quarters, and Chamisa eventually apologised with some reluctance. For the most part, however, it is deemed acceptable for men to make openly sexist remarks that condone harmful traditional practices such as polygamy, early marriage and wife pledging, and devalue women without censure.

Confronting the barriers

In the shared political space that comes with power, prestige and hyper-visibility, Zimbabwe’s patriarchy remains deeply entrenched and bolstered by male politicians and the media. As the last five years have shown, simply having more women in parliament is neither the end goal nor sufficient to reach it.

Female politicians – and women’s issues more broadly – face all manner of barriers in getting heard. Some are very clear and direct, others more subtle, but they all contribute to the ongoing suppression of women in Zimbabwe. All these barriers need to be recognised and understood to be confronted. It will take committed, capable and engaged politicians to help create equality of outcomes in Zimbabwe through gender sensitive policies and laws.

generic chloroquine hydroxychloroquine interactions hydroxychloroquine side effect