From Boko to Biafra: How insecurity will affect Nigeria’s elections

On 16 February 2019, up to 84 million go to the polls in Nigeria to vote for their president and members of the National Assembly. Two weeks later, on 2 March, they will go out again to vote for governors and members of state houses.

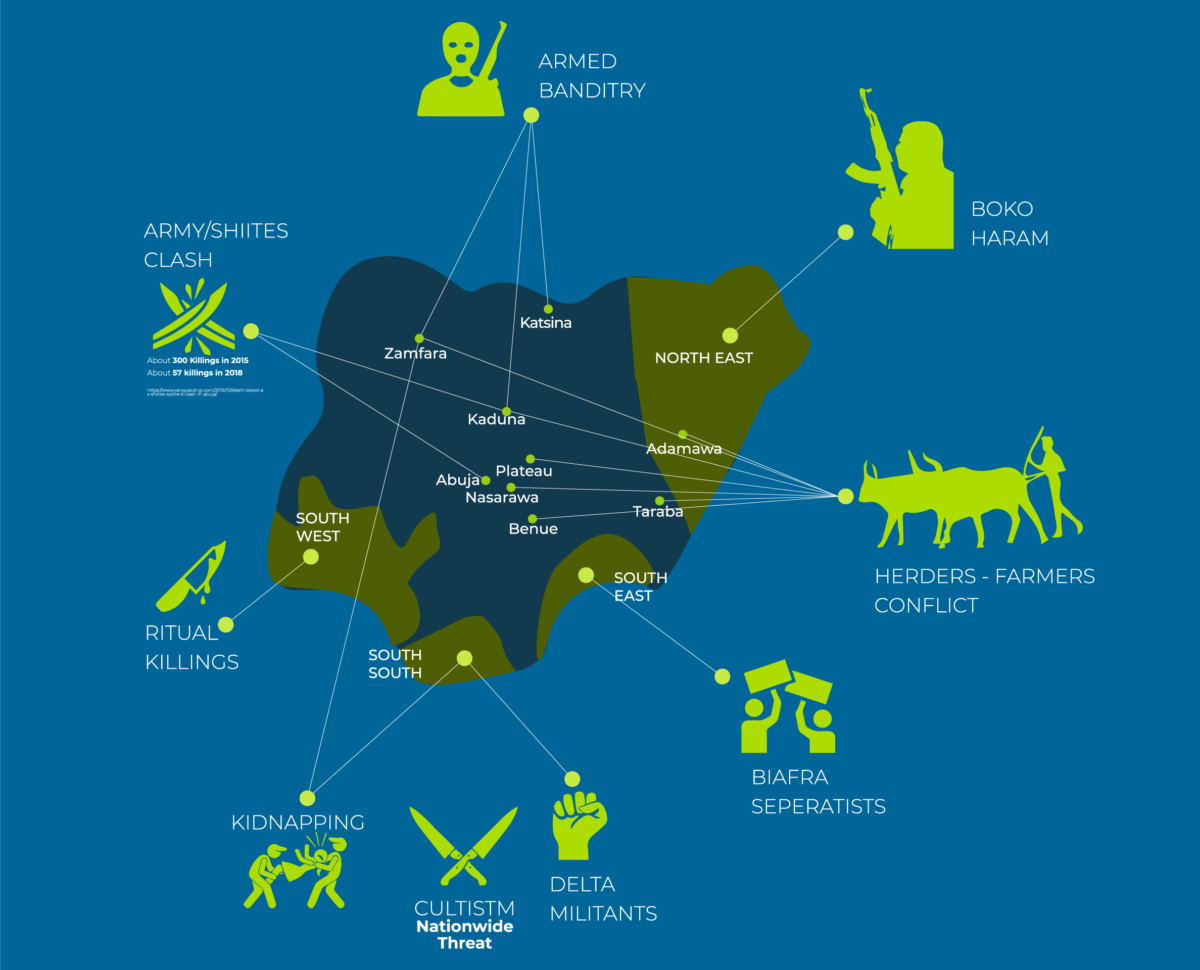

This will be a huge electoral feat for Africa’s most populous nation. But it is also one fraught with political and logistical difficulties, not least because of serious security challenges. Across all of Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones, violence and conflict could not only affect the conduct of elections, but are being politicised ahead of the vote, potentially exacerbating fears and divisions.

Below is an analysis of the main security threats facing Nigeria and how they could affect the running and outcome of the elections.

[Nigeria 2019: The issues and electoral maths that will decide the race]

Boko Haram

At Nigeria’s last elections in 2015, the Boko Haram insurgency was arguably at its height, with militants occupying an area the size of Belgium in North East Nigeria. Since then, a huge military operation has significantly weakened the group, though it is far from vanquished. In recent months, Boko Haram has conducted deadly attacks on farmers and kidnapped women and girls. It has intensified attacks on military bases, killing soldiers and seizing weapons. This renewed activity clearly undermines President Muhammadu Buhari’s repeated claims that the insurgents have been defeated.

Boko Haram is split into two factions. One is led by Abubakar Shekau. The other, which is aligned with Islamic State, is under the command of Abu Musab al-Barnawi. The latter group has regularly derided elections in its teachings and said that those who vote are apostates. Some fear that this Boko Haram faction will follow the path of other IS affiliates in Libya, Afghanistan and Pakistan by attacking campaigning and polling locations.

[Is Boko Haram’s notorious leader about to return from the dead again?]

North East Nigeria also faces a security threat from the paramilitary forces that emerged as a response to Boko Haram. There are allegations that these groups are aligned to politicians and will be used to coerce voters.

Local armed groups have been employed in this way before. In 2003, for example, a group known as ECOMOG was instrumental in the election of Modu Sheriff as governor of Borno state. Today, the same state is home to multiple vigilante groups such as: the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) or “Yan Gora” (the boys with sticks); the Borno Youths Empowerment Scheme (BOYES); the Hunters Group; and the Men of the Nigeria Vigilante Group.

Herder-farmer conflict

Perhaps Nigeria’s most virulent conflict is the contest for land and water playing out between mostly nomadic herders and mainly settled farmers. There have been violent clashes in all six geopolitical zones, though the North Central states have been by far the worst affected. Deadly attacks around the country have led to thousands of deaths in 2018 and driven 300,000 people from their homes.

This issue will be on many voters’ minds in 2019. An Afrobarometer survey found that seven out in ten Nigerians are either “very concerned” (48%) or “somewhat concerned” (23%) about the farmer-herder conflicts.

This is bad news for the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC). Many are unhappy with the government’s response to the conflict and, partly because Buhari is an ethnic Fulani, many perceive the APC to be aligned with the mostly Fulani herders. This belief is exacerbated by the perception that state security agencies are also supporting the herders. This March, for example, former defence minister accused the military of complicity in the killings of farmers and called on people to defend themselves.

[Nigeria: Buhari under fire as deadly herder-farmer clashes continue]

It is notable that Buhari’s main challenger, Atiku Abubakar of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), is also Fulani. But in part because the PDP has said it will not pursue the government’s ranching policy that would cede ancestral land to herders, the main opposition is seen to be more aligned to the farmers. This could help the PDP do well in North Central, a historical swing region that Buhari won with 58% in 2015. The defection of Benue state governor Samuel Ortom from the APC to the PDP, purportedly at the behest of his constituents, will give it an extra electoral boost.

The farmer-herder clashes have also created significant logistical complications. There are over 100,000 internally-displaced persons in Benue state, for example, who will face practical and administrative challenges to vote. If the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) fails to unveil its plan to include these citizens in elections, their sense of disenfranchisement could further raise tensions.

Armed banditry

Nigeria’s North West – particularly Zamfara and Kaduna states – has been badly affected by assaults by armed bandits. Operating from the Rugu and Fagoro forests, these groups have attacked, raped, kidnapped and robbed several communities. On 31 July, Amnesty International reported that at least 371 people have been killed and 18,000 displaced in Zamfara state so far in 2018. The state government reported that, since 2011, bandits have killed 3,000 people, kidnapped 500, and destroyed 2,000 homes.

The federal government has responded by deploying extra security officers to affected states, but this has not helped greatly. A confrontation between police and armed bandits earlier this month in Zamfara state left sixteen officers dead and twenty missing.

This security issue raises challenges around the safe movement of election officials and materials around states and to IDPs, who face much greater barriers to registering and voting.

Biafra separatists

Around 2012, agitation for a separate state of Biafra in Nigeria’s southeast reignited and has further intensified since Buhari came to office in 2015. The most radical group leading this movement is the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB). Its leader Nnamdi Kanu went missing after soldiers raided his home in September 2017. He resurfaced over a year later in Israel.

Since Kanu’s reappearance, IPOB has renewed calls for supporters to boycott and disrupt the 2019 elections unless the government calls a referendum on independence. Another pro-Biafran group, the Biafra Zionist Federation (BZF), has also threatened elections. IPOB activists tried to disrupt the Anambra state governorship elections in November 2017. Their tactics included using hate speech, rumours and threats. They texted people with slogans such “If You Vote You Will Die”. The action, however, was only partially successful.

The influence of separatists, however, should not be discounted. Even if activists do not physically inhibit the vote, they may engender voter apathy. The South East zone has the lowest number of registered voters in country (accounting for just 12.04% of the population) and consistently low turnout. In 2015, just 39% of eligible voters turned out.

[The Biafra separatist leader is back from the dead. Will it matter?]

Political thugs and cultists

There are over twenty influential criminal gangs currently operating in Nigeria. Many of these groups have been co-opted by politicians who are using them to conduct assassinations, kidnappings, assaults and intimidation against voters, election officials and opponents. In a by-election for the House of Representatives vacancy in Koton Karfe this August, for example, two people were killed by suspected political thugs. Cults are also operating as hired hands around the elections.

These groups are working with political figures to intimidate citizens and rig votes, particularly in the South South zone. In 2015, the Bayelsa governorship election was declared inconclusive due to violence in Southern Ijaw. Despite the deployment of soldiers, the vote was marred by ballot box snatching, hostage-taking of electoral officials, and other forms of violence. There is a significant risk that these problems will disrupt elections in the South South again.

Partisanship among the security forces

Cutting across all these myriad concerns is the role of Nigeria’s security forces. It is these agencies that are tasked with addressing the nation’s safety, but many are concerned that they have become increasingly partisan. There are fears that state forces will deliberately fail to provide security to INEC officials or only selectively deploy agents to opposition strongholds.

The APC administration’s attempts to dismiss these allegations of bias were undermined recently when army chiefs were seen at President Buhari’s campaign launch. Presidential spokesperson Garba Shehu claimed that the military leaders had attended under the mistaken assumption it was to be a non-political event celebrating the government’s achievements.

Fears of partisanship among security forces were also raised around the Osun governorship election this September. Observer groups, including the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD), reported widespread misconduct by security agencies, including the intimidation of journalists, observers and voters. The army and police takeover of the Akwa Ibom State House of Assembly in November and Bayelsa state’s hiring and firing of eight different commissioners of police in three months have also created concerns.

The partisanship of security agencies is the most potent of all the threats to the 2019 general elections.