President-on-a-Leash Tshisekedi and the DRC’s paradoxical new politics

After a long struggle, the people have (kind of but not really) got what they want with President Kabila (kind of but not really) conceding power.

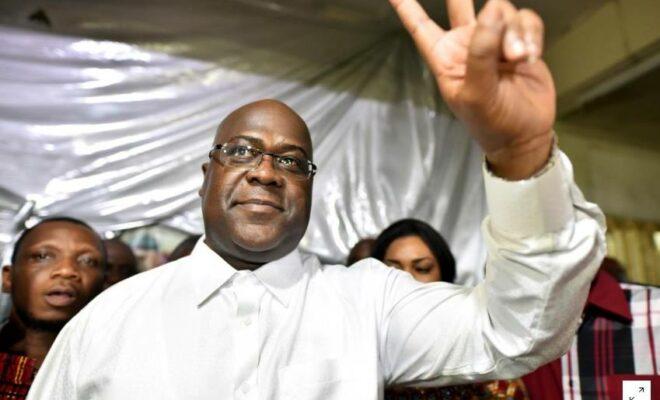

The DR Congo’s new President Tshisekedi officially won the December 2018 elections.

When Felix Tshisekedi takes oath later today, he will become the Democratic Republic of Congo’s (DRC) fifth president. His inauguration will mark the country’s first peaceful democratic transition of power – and to an opposition leader at that.

On paper, this is a textbook example of successful democratisation. But that narrative is undermined somewhat by the fact that Tshisekedi was almost certainly not the true victor of the December 2018 elections.

According to official results from the electoral commission (CENI), Tshisekedi won with 38.6% of the vote; opposition leader Martin Fayulu came in second with 34.8%; and the regime’s candidate Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary was third with 23.8%. But these tallies vary hugely with both leaked numbers from CENI’s computers and data collected by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference’s (CENCO) 40,000 observers. Their figures suggest that Fayulu was the real winner with an overwhelming 59.4%, and that Tshisekedi and Shadary got around 19% each. Fayulu challenged the results, but the constitutional court upheld them.

[Congo’s 2018 elections: An analysis of implausible results]

In many ways, a Tshisekedi victory was the outcome no one was expecting. Outgoing president Joseph Kabila has spent the last few years clinging onto power. In the run-up to 2016, the year his mandate officially expired, he explored changing the constitution so he could run for a third term. When that didn’t work, he simply delayed elections for two years until domestic and international pressure forced his hand.

Some suspected Kabila would still find a way to run, but as the vote approached, the presidential majority known as the Front Commun pour le Congo (FCC) nominated Shadary as its candidate. The plan was presumably to use its extensive power and oversight over the electoral process to ensure his victory and the continuation of Kabila’s rein by proxy. But Shadary proved so unpopular that even with heavy manipulation, it would have been impossible to declare him the winner without triggering mass protests. By contrast, Fayulu gained the backing of several opposition parties and soared in the polls.

Faced with this conundrum, it is widely believed that Kabila improvised a deal. He couldn’t install his own hand-picked candidate, so came up with an arrangement with Tshisekedi instead. The regime conceded the presidency to the second-placed opposition leader, but managed to keep Fayulu – and crucially his powerful supporters in former vice-president Jean-Pierre Bemba and former Katanga governor Moise Katumbi – out of power.

On a leash

Nonetheless, after 18 years in office, the deeply unpopular President Kabila is finally stepping down. The DRC has a new president. Yet below the surface of this monumental shift, much has not changed. The FCC maintains its firm grip on power.

In December 2018, the Congolese people did not only vote for a new president, but for members of the national parliament and provincial assemblies. And to everyone’s surprise – or maybe not – the ruling FCC won overwhelmingly, significantly strengthening its majority by picking up 350 of the DRC’s 500 parliamentary seats. Tshisekedi’s Union pour la Démocratie et le Progrès Social (UDPS) won just 49, or less than 10% of the total. The FCC also won the largest number of seats in all 26 provincial councils. This means it can elect all the country’s governors, giving it a monopoly on decision-making and access to financial resources at this level.

President Tshisekedi will also find his powers stymied in other respects. The army top brass is made up of key Kabila allies, installed a few months ago. And the powerful patronage networks that gravitate around Kabila remain in place. Tshisekedi’s team may try to break this up, but will find it tough-going. The FCC will be reluctant to offer the new president and his vice-president Vital Kamerhe much more than crumbs. It might offer to organise a state funeral for Tshisekedi’s late father and veteran politician Etienne, whose remains have been in a morgue in Brussels since his death two years ago. It may offer up some key managerial posts in parastatals, giving up access to some public finances, and oversight of some minor ministries. But strategic positions such as security, foreign affairs and the economy will most likely remain under the close watch of the regime.

The outgoing president may also have a final card up his sleeve to keep a leash on his successor. Rumours have been circulating for months that Tshisekedi included a faked diploma from an institute in Brussels in his registration to run for president. Last week, it emerged that the Congolese courts had asked the Belgian state to examine the document, which it confirmed was fake a month before the elections. This opens up the possibility that the DRC’s constitutional court could choose to impeach Tshisekedi at any time.

Tensions and paradoxes

Beyond Tshisekedi’s paradoxically tenuous presidential position, the elections have introduced many other new contradictions into the DRC’s political system.

There are fresh tensions within the FCC itself, for example. Many local strongmen claim the parliamentary elections were rigged too and that their seats were given to national heavyweights as part of some high-level deals by the regime. These disgruntled figures have been left to protest or simply leave the ruling coalition.

[How to get ahead in DR Congo politics: A flatterer’s guide]

The internal cohesion of Tshisekedi and Kamerhe’s coalition known as CACH is not high neither. The new president and vice-president have a bad personal relationship. Their ad hoc alliance is built on convenience rather than a natural affinity, and the sharing of responsibilities of privileges among their supporters could prove tricky.

And finally of course, there is the widespread frustration and growing mistrust among the 60% of the electorate that voted for Fayulu.

Watching on from outside the Congo, African institutions also face a fascinating dilemma. Above all, they fear the negative impacts that instability in the DRC could cause for their own domestic situations. This is what motivated them since 2016 to put pressure on Kabila to step down and why they are now in a complicated bind. On the one hand, they know the election was not credible and that Congo’s new improvised political set-up is unlikely to be sustainable in the medium- or long-term. And yet, it seems to be the only way to avoid chaos in the short-term.

A rigged Shadary victory would have led to bloodshed. A Fayulu victory would never have been allowed by the regime. But an unexpected Kabila-brokered Tshisekedi win at least defuses any immediate explosive momentum. It is not surprising then that African multilateral institutions eventually endorsed the elections and have welcomed the Congo’s new President-on-a-Leash Félix Tshisekedi.

The West for the most part is willing to work with the FT Government as Western Democracies do not wish to encourage further violence in DRC publics which would emerge if a contestation in who legitimately was the election victor.

As suggested earlier, the Kabila Cadre did rig the election with CENI connivance as the Kabila Cadre feared both Bemba and Katumbi who would indeed have exacted revenge inclusive of financial accountings in targetting all Kabila Cadre acolytes in forcing full disclosure inclusive of accountability in how assets were obtained.

There is an old Congo saying which adumbrates most excellent the Kabila Cadre rebel mentality in power holding, as this DRC tribal parable opines—”a monkey would rather perish with food in the mouth than share with another monkey”.

Joseph Kabila has no intention in relinquishing his grip on power either direct or indirect!

The December 30 Election was ‘Rigged’!

Felix Tshisekedi and Joseph Kabila did facilitate an agreement in the event the Kabila Cadre was unable to flog their dead horse, aka Shadary across the electoral finish line.

This agreement between Kabila and Tshisekedi is known among the professional intellectual elites in DRC, notwithstanding many of these elites live in fear of reprisal, as a significant number of these elites in DRC are most loathe to be associated with an element tainted touched by the Kabila Cadre.

Tragic, the DRC Constitutional Court is Potemkin, in being a court comprised of Kabila Cadre imposed acolytes who make rulings as ‘suggested’ by the Kabila Cadre.

Felix Tshisekedi is ‘dim’ in his intellectual curiosity along in being weak in self esteem as Felix T is not his father Etienne T who notwithstanding ET accepting wealth from sources less than robust in administrative legitimacy did offer a credible alternative in DRC outreach programs.

In Felix Tshisekedi—‘meet the new boss same as the old boss’—lyrics by The Who—as the electoral imposition of FT by the Kabila Cadre upon the peoples of DRC was deemed a sound alternative as Emmanuel Shadary attributed to his direct connection to Kabila was reviled by many many of the DRC peoples via the ballot spoke truth to power.

The Kabila Cadre in no manner of form or substance in public administration was going to enable Jean Pierre Bemba and Moise Katumbi [agreed, miscreants both] to roll in roiling back in returning to DRC publics seeking punitive revenge in stripping the Kabila Cadre of wealth and in specific people, personal freedoms without a fight.

The fine peoples of DRC are the real loser if this potemkin election result is allowed to remain binding by the Constitutional Court.

DRC political social publics will be even more trenched within an ethos utterly profoundly transactional suggesting more degradation in DRC public institutions representing rule of law.

The DRC Constitutional Court ideally should structure its decision on Martin Fayulu’s brief alleging electoral improprieties based solely on evidence, meaning CENI must provide to the Constitutional Court in public, all election results poll by poll which can then be explored in evidentiary cross examination attesting to electoral poll validity, or not.

The most fine people of DRC are pleading for their voices to be heard unencumbered by ‘puissance’ imposed by this Kabila Oligarchy who are most most most reluctant to give up any prerequisites in power privilege.

C’est sera vraiment triste as this DRC Constitutional Court has recently elected to make a mockery of judicial process inclusive of evidence based judicial procedure in confirming an election count profoundly suspect.