Duped through dating apps: Queer love in the time of homophobia

In Nigeria, the LGBTQ community is vulnerable to extortion, making dating an often dangerous pursuit.

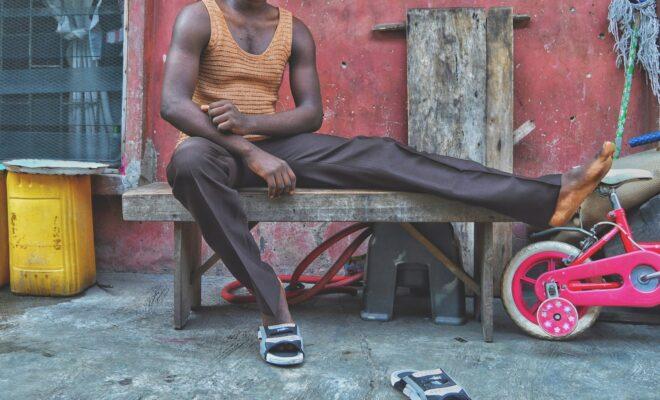

In Nigeria, LGBTQ individuals such as Uzor face widespread homophobia. Credit: Ikenna Ogbenta.

This article was made possible by the generous “patron” subscribers of the Africa Insiders Newsletter. The little bit extra they give goes to funding African Arguments’ unique reporting.

It was New Year’s Eve when James*, 29, agreed to meet up with a man he had connected with on the dating app Grindr. They were beginning to get to know each other through the LGBTQ platform and they arranged a time and place. But things did not go as James expected.

Rather than getting to know the man he thought he’d been talking to, he was lured to a secluded area where he was surrounded by a group of men who threatened him with violence and said they would expose his sexuality unless he paid up.

“I had to call my colleagues to ask for money although I couldn’t tell them what exactly it was for,” says James. He gave his attackers N25,000 ($70) and his phone before they let him go.

James’ experience is far from unique in Nigeria. According to The Initiative for Equal Rights’ (TIERS), there were 286 documented cases of violations due to people’s real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity in 2018. Of those, the most widely reported type of attack was blackmail with 70 recorded incidents. In many instances, these crimes are premeditated and set up through dating apps like Grindr, Badoo and Man Jam.

In Uzor’s case, it was a platform called 2go, which he had used successfully to meet men in the past.

“I was 19-years-old and I couldn’t meet gay men in my area without 2go,” he says.

One day, however, a man he met through the app invited him back to his house. Uzor was barely through the door when he was rushed by five men brandishing knives and sticks. They took his clothes, cash, ATM cards, both his phones and verbally abused him.

“They told me I was smelling, that I had anal cancer and had to wear diapers,” says Uzor.

The men then forced him to record videos admitting he was gay and threatened to send them to his parents. At the time, Uzor had not yet come out to his family who, like many in the country, are deeply religious. Nigeria is around 46.3% Christian and 46% Muslim, and interpretations of these religions tend to be highly conservative. In the north where Islamic Sharia law is implemented, gays and lesbians can legally be stoned to death.

“Now, my parents are cool with my sexuality but then they weren’t,” says Uzor.

Nigeria’s religious conservatism contributes to widespread homophobia, which is also reinforced politically and legally. The 2014 anti-gay bill, for example, criminalises some homosexual relations with up to 14 years in jail. In 2018, police raided a hotel and arrested over 50 men accusing them of being homosexuals. This January, a police officer warned gay people to leave the country or face criminal prosecution in an Instagram post.

Among other things, these laws make it easier for criminals to extort members of the LGBTQ community. After Obed, a Nollywood filmmaker, was beaten and robbed following meeting someone through Grindr, for example, he had to weigh up whether or not to report it. He was arrested by the Special Anti-Robbery Squad alongside his attackers and when he did tell the police, he spent almost three days in jail before his brother secured his release, parting with N200,000 ($555) in the process.

“The real predators were not the guys that held me hostage that night, but the policemen I believed came to rescue me but turned to extort and humiliate me,” he says.

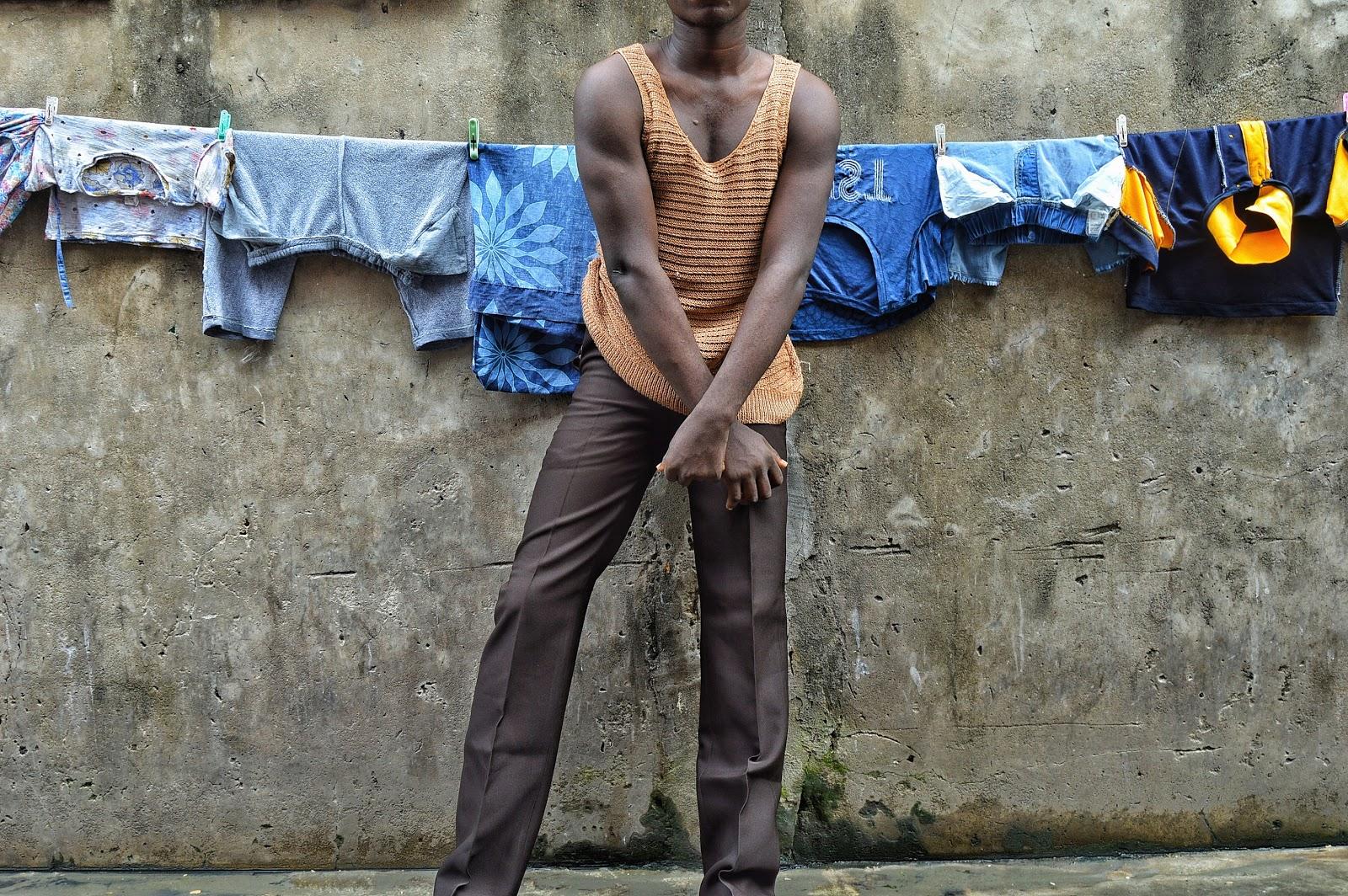

“I just woke up one day, called a family meeting and said, ‘I like guys, I’ve had sex with guys,’ I was fucking bold,” says Uzor of coming out. Credit: Ikenna Ogbenta.

In order to combat these crimes, LGBTQ Nigerians are devising ways to warn each other of the dangers. One of these is Kito Diaries, a blog set up in 2014, which has a category called “Kito Alert”. In this section, users such as Obed have written about their experiences of being ambushed or targeted by police masquerading as gay men on the internet. The word “kito” is a Nigerian gay term used to describe the experience of falling into the hands of swindlers.

For admin Walter Ude, who verifies and vets entries to ensure their authenticity, projects such as these are essential. Members of the LGBTQ community must support each other since, he argues, they are “not assisted by law enforcement in this battle to survive targeted anti-gay crimes”.

“Running Kito Diaries showed me how alone the LGBT community essentially is,” he says.

Survivors’ stories therefore provide a means whereby people can share experiences as well as inform one another of the threats. Some posts even warn readers of specific known perpetrators such as in the recent entry entitled Tell someone who doesn’t read Kito Diaries to beware of Idowu Adeyemi and his partner.

In part thanks to initiatives such as this, Ude says that queer Nigerians are taking greater precautions and that reckless meetings with people met on the internet are becoming less frequent.

This trend may also be connected to dating apps taking matters more seriously. Many companies had been criticised for being slow to respond and it was not until June 2018, for instance, that Grindr joined the awareness campaign against impostors and published a list of dangerous areas as well as contact details for organisations such as TIERS.

“On our safety page, we list the most common neighborhoods in eight Nigerian cities where Grindr users have been lured for entrapment,” the company wrote to African Arguments. The representative also cited other initiatives such as a safety guide in Nigerian Pidgin, Nigerian users’ free access to privacy features such as the ability to hide the Grindr app, and an upcoming Nigeria-specific safety page being created in collaboration with TIERS.

For some users, this will bring some relief, but for many who have already fallen victim through the app, it is too little too late.

“I still meet people to have sex with on Facebook but no one should use Grindr,” says Uzor. “It’s unnecessary and dangerous.”

Others like Douglas, who was attacked after meeting someone through 2go in 2014, have ruled out in-person meetings with online contacts altogether. “Once the conversation gets to, ‘where can we meet?’ I zone out,” he says.

*Names have been changed to conceal identities.