“They were useless”: What about South Africa’s forgotten rural voters?

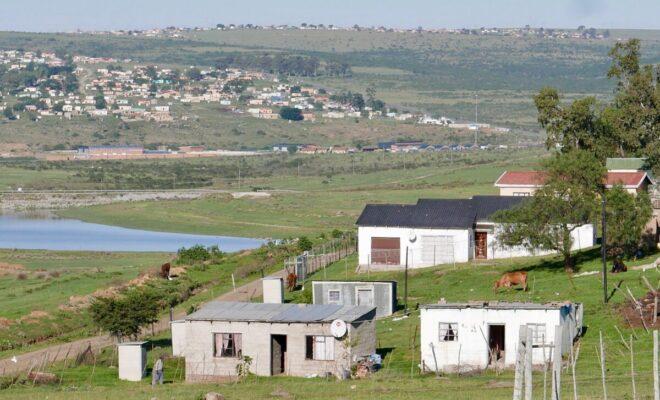

Attention ahead of the 8 May elections has focused on major cities, but what are voters saying in overlooked rural areas where a third of voters live?

Will opposition parties like he Democratic Alliance be able to pick up disenchanted rural voters in the South Africa elections? Credit: Martin Plaut.

This is the first instalment of a three-part series around South Africa’s 8 May general elections.

Asanda Qosha was walking briskly along a dirt road in KwaTshatshu, on the outskirts of King Williams Town, in the Eastern Cape when I met him. Smartly dressed, he was making his way among the scattered houses, set in the green, rolling hillsides.

Qosha was on his way to the town of East London to pay his taxes. A confident, well-built man, he supports the African National Congress (ANC), the party that has been in power in South Africa since 1994. Yet, like so many South Africans, he has no job. Unemployment officially stands at around 27% and is among the highest in the world.

“I have had no official job since 2011, so I started up my own construction company,” he explains. Qosha has relied on small contracts from the government ever since. “It’s the only way,” he says, “the private sector just goes with the big companies.” Now, he is on his way to pay R5,000 ($346) he owes in back taxes. It’s hard, but it needs to be done if he’s to keep getting government contracts.

So what does Qosha think of the government? “The ANC is the only vehicle for people to get out of poverty,” he insists. At the same time, however, he has no illusions about the party. “The ANC is very corrupt. It really bothers me. They are robbing our poor: that’s why there’s no housing, roads or clinics.”

Asanda Qosha, a rare ANC supporter in the eastern Cape, giving the movement’s clenched fist salute. Credit: Martin Plaut.

But Qosha has even less time for the major opposition parties. In his view, the Democratic Alliance (DA), the official opposition, has nothing to offer him. “They concentrate on the [white] suburbs and they don’t speak out when whites are involved in corruption,” he says.

He dismisses the other major party, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) of the radical Julius Malema, too. “They will scare off the investors with their demands for land nationalisation,” he believes. With that, he spots a passing car, waves it down and hops in, giving me a broad grin as he disappears down the road in a cloud of dust.

Qosha is no doubt sincere, but in three days of travelling across the towns and villages of the Eastern Cape, he was the only ANC supporter I came across. This region has a reputation for having some of the worst services in the country and is plagued by corruption. Political leaders pay fleeting visits to the rural areas, but their motorcades are soon gone and many feel forgotten by those who rule them.

I met plenty people who were not going to vote, and others who might grudgingly support the EFF or DA. But here, in what was once the heartland of the ANC, there is little enthusiasm left for the party that led the country out of apartheid. Leaders like Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki came from this region, but the years of corruption associated with President Jacob Zuma have shaken even loyalists to the core. The current president, Cyril Ramphosa, has yet to make his mark.

Lindiwe Kaba says she would like to see the ANC lose power in the South Africa elections. Credit: Martin Plaut.

Some lost faith in the ruling ANC a long time ago.

The EFF has a large office on the high street of King Williams Town. Its windows are plastered with slogans, and their hallway is full of posters proclaiming “Julius Malema, Son of the soil”. This reflects his promise to take state control of all land.

They send me to see the mother of one of their councillors, Maseer Lindiwe Kaba. Mrs Kaba is a dignified old lady, sitting erect in her armchair, watching an Indian soap opera on her large television. She tells me from the start that she won’t say how she will vote in Wednesday’s elections.

So who did she vote for in 1994, the first truly democratic elections in South Africa? “I voted ANC. But when he came from jail Nelson Mandela was too old already. After that there was Mbeki and the rest. They were useless!” she says, wagging her finger for emphasis.

“Now they must go to bed and go to sleep,” she continues. “It would be a blessing from God [if they lost power]…I don’t care if the next government is DA or EFF; I don’t want the ANC.”

Kaba complains that political corruption is widespread, while South Africans like her struggle to pay for food and electricity or find employment. “My daughter Pindi got a good education and she wanted more, but she can’t get a job,” she says. “But Mr Somebody takes millions. The ANC’s good plan is to eat money!”

Before the election, the ANC arrived with trucks to deliver food parcels, but Kaba refused them. “I didn’t touch it,” she explains. “When they came in 2014 [the previous election], I told them they must not come to my gate again. I only have my pension – and they can’t take that.”

It’s a heart-breaking story and one that is told across this region.

In reality, no one has a clear idea of how the election on 8 May will turn out. In 2014, the ANC won with 62.15% of the vote. None of the polls predict that it will do as well, but their figures vary wildly. They suggest that the ANC will get anywhere between 49.5% and 61%, but everything depends on the turnout.

Citing these discrepancies, Judith February, one of the country’s most respected commentators, concludes: “It’s therefore probably best to ignore the polls, vote on 8 May – and wait.”