Living in Translation

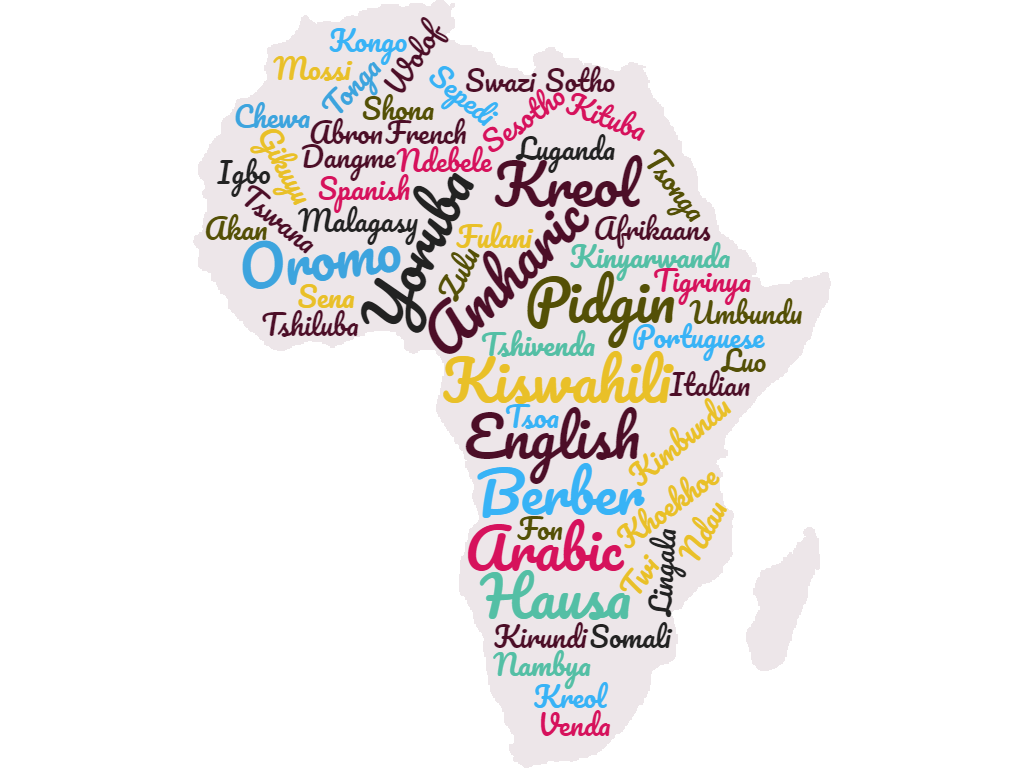

Welcome to a new series of articles, guest edited by Nanjala Nyabola, exploring the worlds our languages have built across Africa.

This is the first article in the seven-part series Living In Translation about language and identity. They are guest edited by Nanjala Nyabola. See all the articles here.

I was recently asked to do a live segment for a Kiswahili language station on a new data collection exercise spearheaded by the Kenyan government. I said yes because I had literally just published a 268-page book that touched on the subject, and because Kiswahili is one of my primary languages. This should be easy, so I thought. Like most Kenyans, I grew up dipping in and out of English, Kiswahili and my mother tongue. Surely speaking Kiswahili for three minutes on live television should not have been a problem. I was a Kiswahili teacher for some time for crying out loud!

Except it was more of a problem than I care to admit. I ummed and ahed my way through the interview, stumbling from signpost to signpost, trying to find the grammar and vocabulary to analogise words and concepts I knew like the back of my hand in English. How do you say “data privacy is critical to balancing the power between the citizen and the state” in Kiswahili, I wondered?

This awkward, live and internationally-televised experience reminded me that fluency is more than merely knowing the language. Fluency is seeing past the hard edges of definitions and vocabulary to the softer, nebulous contours of conceptualisation. Fluency means living in a language fully.

By now the research is in and recognises that language is more than just a string of words. It defines the shape of our world, how we perceive colour and taste, and even the social and political possibilities of our societies. Research on multilingualism confirms what those of us who speak multiple languages routinely know – we are different people who see the world differently depending on what language we are thinking in and speaking. Some languages allow us to be more humorous, which is why on social media for example, many Anglophone Africans will begin a tweet in English and finish it in Zulu, Xhosa, Swahili, Shona or Ndebele. Some languages are just so compact and malleable that we pick them up, break them, and wield them to suit our needs: not English but our Englishes.

We use language to name things and then place them in their proper social and political order: by alphabet, by group, by definition, by rank, and by any other categories that we perceive through the combination of experience and inheritance. Thus for Kiswahili, Arabic and Amharic speakers, time is not just measured between one hour and the next, but also relative to the sunrise and the sunset, so that 7 am is saa moja, the first hour after sunrise when we wake up and tackle the day. The root word ganga, which conjugates as “doctor” in various Bantu languages in Africa, survives as gangan in Haitian Creole and carries with it a history of slavery across the Atlantic, through time and into the present day. Language is not just a string of words. It is our orientation towards the world: a vessel for our histories of migration, connection and disconnect, place and time, longing and desire, as well as being.

The worlds our languages have built

With this in mind, we here have set out to do something that was admittedly ambitious but hopefully interesting and even, dare I say, cool. We reached out to writers we love and admired and asked them to use language as an entry point for thinking about society and politics in Africa. We wanted to get a taste for the some of the histories that news cycles miss and of some of the things our identities might unknowingly be anchored in.

It’s certainly not unprecedented to have language used in this way. Ngugi wa Thiong’o has published extensively on the multiplicities created by Kenya’s linguistic heritage. Peter Ekeh’s conception of three publics is rooted in the colonised self, navigating overlapping yet barely-meeting worlds created and sustained fundamentally by language. Ali Mazrui also published on the impact of the English language on the African mind, saying in a paper published alongside his then-wife Molly “the ways of thought of a people are inseparable from the language that they use”.

What we hope is new and interesting about this project is that we have featured new voices on the continent carrying this debate forward in contemporary terms, grappling not just with the shadow of European colonisation but looking within the continent itself. First, we invited people from countries from whom we rarely hear. Then we invited these brilliant people to look at the same things in different ways.

South Africa through Kiswahili and xenophobia rather than the tussle over Afrikaans. What should be the place of such a language in a newly-liberated nation with a multiplicity of languages of its own? Is the place of the same Kiswahili, an African language with an ethnic group of its own, different when it gallops across Tanzania riding upon a history of European conquest and African trade? Does declaring a regional language national make it so? We are also invited to dance to the beat of Fela’s pidgin while imagining how it does the heavy lifting of cobbling together a national identity out of Nigeria’s pluralities. What kind of polity does pidgin make possible in a Nigeria where people have died for their ethnic identities?

We invited writers from countries with contested identities to use language as a tool for reflecting on this contestation. Western Sahara, “Africa’s last colony”, speaks a dialect of an African language – Hassiniya – as its official language. The struggle for independence against Morocco, which has until recently resolutely faced Europe, has incubated a staunchly African identity in the Saharawis. Will this change now that Morocco is finally turning around to face Africa?

Can Creolité give Mauritius access to an African identity that has long been rejected or in some cases denigrated? Can it be an anchor that, by binding up the island’s present with its ugly past of slavery and invasion, tie it to the mainland? What is the place of Amharic, the national language of the only country in Africa that was never colonised by Europeans, in an Ethiopia characterised by invasion and conquest? Does it evoke the same pride inside Ethiopia as it does outside it? Can it?

There is no grand objective with these essays – really this was a project that we indulged in simply because we could. For African writers and thinkers, that is political enough. Today, to be an African is to have too much of your thinking and theorising forcibly directed towards grand, ill-defined concepts like “development”. Sometimes a meandering walk through a set of ideas that make no meta-claims beyond asserting their existence is political statement enough. These essays are a statement on the complex worlds that language is building in various African societies, feeling through the ambiguity of identity and being to get a better grasp of the hard edges of our politics.

Sit here with us for a while and see the worlds our languages have built.

Nanjala will be doing a twitter chat from the African Arguments handle on Thursday 9 May at 10am GMT (i.e. 11am West Africa standard time; 12pm Central Africa Time; 1pm East Africa Time). Chat to her and ask her about all things language and identity using the hashtag #LivingInTranslation.

…and many more: Oshindonga and Oshikwanyama from Northern Namibia; Chitumbuka from Northern Malawi, Lozi…..and so on….