For Naija, We Dey Kampe

Adaptable, jazz-like and subversive. How Pidgin English, the language of Fela Kuti, turns competitors into comrades in Nigeria.

Nigeria night life. Credit: Oluwaseun Duncan.

This is the second article in the seven-part series Living In Translation about language and identity. They are guest edited by Nanjala Nyabola. See all the articles here.

It is a cold evening and Abuja is in the grips of the harmattan, gathering sand from the Sahara further up north to pour into the Atlantic at my country’s feet.

We take a last turn and a gate appears to the left with the word COMPASS spelled out in yellow bulbs. I ease my car beside the silent generator; Aminu stashes his tablet under the seat. The bar itself is atop a small hill, twenty-four concrete steps above the car park.

“Chief,” Peter yells when we reach the top. He is dressed in a sky blue long sleeve shirt over a black trouser. “How far? Two days o! Oga Aminu, abi you still dey vex?”

“Bros, I no been dey,” I say, “I just enter town.”

Peter leads us to our usual table, set under the stars, offering a panoramic view of the Nigerian capital’s flickering lights. The grill master shows up and we place our order. He brings a cold-hearted Legend stout for me and a “33 lager for Aminu. Our business partner, Chidi, arrives out of breath.

“Chairman!” he says, shaking Aminu’s hand and fist bumping me. He turns to me, “Aminu na mad man o. Chai! Him tell you about the day of fight for here? As Aminu small like this!”

Aminu, smiling now, had given a good account of himself in the bar fight last week. It had started when some local thugs demanded Peter switch the music from Fela to something else.

Sitting there, drinking beer, you would think we were brothers. But Aminu is Fulani, descendant of cattle nomads. I am Igala, long sedentary by the shores of the River Niger. Chidi is Delta Igbo – “bread and buttered” as he would like to say – in Warri in the south. We are, if stereotypes are allowed, from competing ethnicities. But we are connected by a Nigerian pidgin English and rebel music. We should not trust each other, yet here we are.

A vast national laboratory of language

Nigeria’s population of almost 200 million people is divided into 250 ethnic groups. Some number a few thousand members; others have upwards of 40 million. In Plateau State in central Nigeria, there are 48 distinct ethnic groups and a traveller can quickly enter unknown ethno-linguistic terrain within a journey of just a few kilometres.

In this potpourri of cultures, one way we find unity in diversity is in our use of Pidgin English. Also called Naija Languej, this tongue is older than Nigeria itself. Its roots emerged when European traders arrived in Benin, a maritime empire in the southwest that, at its height, controlled what is today Lagos as well as the Niger delta.

The first words of Nigerian Pidgin emerged from the intercourse between the Portuguese and Bini tongues. They largely relate to trade. Eviado, for example, comes from Ouvido, Portuguese for a Customs Inspector. Efenrhinyen, meaning cassava flour, derives from farinha. The custom of calling every male person a Chief or Chairman or Bros comes from the Ibero-Portuguese word chefe, meaning leader or boss. The name of Nigeria’s biggest city today, Lagos, is the Portuguese word for lake.

As the Benin Empire declined and was replaced by independent trading houses in the Niger Delta, the Naija Languej began to take its present form, with English and not Portuguese as the substrate. To this day, the purest Pidgin English is spoken in the Niger delta, particularly the city of Warri where Chidi is from. Following the infamous Berlin conference in 1884 after which Britain started the slow process of creating modern Nigeria, Pidgin stepped in as a clearing house between the colonising British and their new subjects.

In this sense, Pidgin English draws a line from the pre-modern “Niger area” to today’s Nigeria. The language was my people’s first attempt to internationalise ourselves, understand colonisation and, in the same vein, find neutral territory.

Pidgin stems from a healthy curiosity about the world beyond our immediate neighbourhood. This curiosity informs its loose, informal syntax and its portability; its wilful ability to borrow from several native languages; the way it is keen, like jazz, on the improvisational and subversive. What exists today is not in fact a settled Pidgin English but rather a vast national laboratory of language. It was created because of overseas trade; it then helped make some sense of foreign domination. It is a language that remains permanently relevant because of its innate, continuing adaptability to local issues.

Nigerian history is marked by power struggle between three major ethnic groups: the Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo. This competition has often been bloody, featuring a civil war and several coups. Our federation is unwieldy, with a tendency to overheating. As a country therefore, we are always seeking ways to create a national sense of self in our citizens. Pidgin English is one such inclusive system.

No reflection on Pidgin would be complete without an examination of a particular genre of music Nigeria gifted to the world, one intimately connected to the language, the masterwork of just one man.

In 1958, Fela Ransome-Kuti arrived the UK, ostensibly to study medicine. The problem was that he was more interested in jazz than medicine. So he registered instead at the Trinity College of Music just off Wigmore Street in central London. Against a storm of parental opposition, he persevered and formed the Koola Lobitos jazz band in 1961.

By 1969, Nigeria had already had two military coups. A civil war, borne from ethnic competition, was grinding on. This was the year Fela recorded his Los Angeles Sessions and created Afrobeat. His emphasis on more native African musical instruments along with the ideology of Black Power movement fuelled the need for a new language. Fela, then 31, chose the language of the oppressed, working classes who just wanted a simple life. Pidgin English became the vehicle for his rebel music.

This rebel music was played everywhere, from military barracks to beer parlours. Pidgin English became mainstreamed it into the middle-classes and beyond. In Pidgin and in Fela’s songs, a sense of national self began to manifest. In his music, it was clear who “us” was because it was clear who “they” were – the khakistocracy that had taken a country of great promise and made it a third-world basket case. By the time he died in 1997, Fela had galvanised a nation. In 1999, democracy was restored.

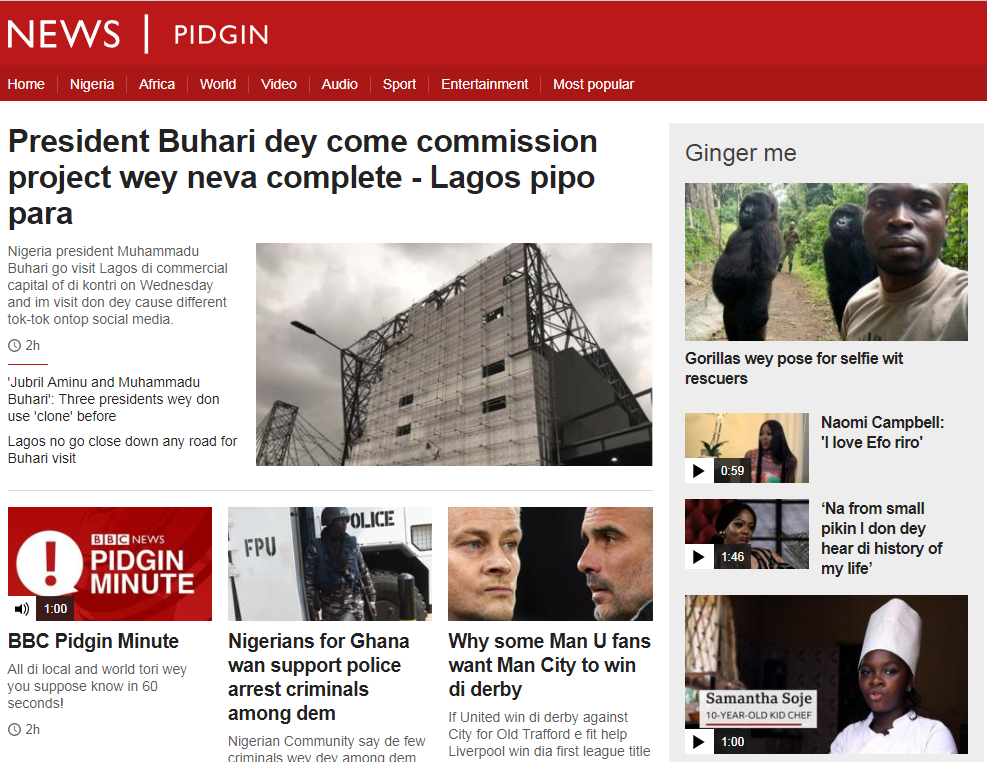

Fast-forward to today and there is a BBC Pidgin English Service that is broadcast from Nigeria and reaches millions of listeners across West Africa. Novels such as Adaora Lily Ulasi’s Many Thing You No Understand have been written exclusively in Pidgin. I recently worked on a project with the New York University to translate a story from the Maqamat of al-Hariri of Basra to Pidgin. Stand-up comedians like Gordons and I Go Die fill up stadiums for shows wholly in Pidgin. Politicians and NGOs alike deploy their communications in Pidgin English, from re-election campaigns to immunisation drives.

As we say, Pidgin na we own, from street to boardroom.

BBC Pidgin was launched by the BBC World Service in 2017.

At the Compass bar, it is time to go. Chidi settles the bill.

We three had met a decade earlier, fresh out of university and called up to the mandatory National Youth Service Scheme (NYSC). Along with many thousand other young Nigerians, we were sent to Awgu, which had been one of the headquarters of Biafra during the war. The NYSC was a post-war creation, part of an attempt to reintegrate the country by sending young people to teach in regions other than those they came from or had grown up in.

One night, within walking distance from dissident General Ojukwu’s fortified bunkers, Aminu and I had gravitated towards Chidi’s portable transistor radio playing Fela’s 1972 classic, Lady. We danced around like schoolboys, singing “She go say… She go say she be lady o” and found ourselves fast friends, exchanging visits during the one-year service, starting a business together later on.

Now, we hug.

“Till tomorrow,” I say.

“Make day break,” Chidi replies, before turning to Aminu. “Bad guy. I go come pick you for morning. Like 9 o’clock. Remember, meeting with Perm Sec na 10:30 sharp.”

“Goodnight, bros,” says Aminu.

Within a minute, we are driving our separate ways, three diversities united in a national experience and a language to communicate it with. In all our heads, Fela is still playing.

This is the second article in the seven-part series Living In Translation, guest edited by Nanjala Nyabola, that will be published across this week. See them all here. Nanjala will be doing a twitter chat from the African Arguments handle on Thursday 9 May at 10am GMT (i.e. 11am West Africa standard time; 12pm Central Africa Time; 1pm East Africa Time). Chat to her and ask her about all things language and identity using the hashtag #LivingInTranslation.

Nice one, bros. This is another City of Memories.

Hello. Can I send in a pidgin poem?

chloroquin side effects https://chloroquineorigin.com/# what is hydroxychlor