From fashion to farming: Surviving and thriving in Kakuma refugee camp

The scorching afternoon sun beats down on Kakuma camp in Kenya’s dry north-east. Home to nearly 150,000 refugees, mostly from South Sudan and Somalia, the busy streets here are lined with corrugated iron homes interspersed with the invasive mathenge tree.

The inhabitants of the world’s fourth largest refugee camp are heavily restricted in what they can do and where they can go. Many have been here for several years and rely on aid from bodies like the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and international NGOs to survive.

However, as in refugee camps across the world, people in Kakuma have also started innovative initiatives to learn skills and find alternative sources of income, life and fulfilment. Here are just a few of them:

The fashion designer

Biclere (standing) talks to a client at her shop while her employees work on other clothes.

Before Shukrani Hota Biclere, 35, fled her home in the Democratic Republic of Congo, she used to operate a bar and design clothes. Now, in Kakuma, the single mother of two has gradually built a new business based on her skills.

“I came to Kakuma in 2010 and because I knew how to sew, I was employed as a tailor at a shop here at the camp for seven months,” she says arranging fashion materials at the Ethiopia market in Kakuma 1 camp. “After that, I decided to start my own fashion shop from my savings, focusing on Congolese fashions since that was what I had been doing back home and my clients loved it.”

Biclere opened her shop in February 2013, but due to travel restrictions, she faced challenges in getting the materials she needed. Through talking to clients, she eventually found a store in Nairobi willing to do business with her remotely.

“With a mobile phone, I only place an order and send money through Mpesa, after which my luggage will be sent by bus to Kakuma here,” she explains.

Biclere sells her clothing mostly to fellow refugees, young and old, as well as to staff from humanitarian agencies in the camp. Complete dresses go for around $25-30 and she says she can make several hundred dollars each month.

From the proceeds, Biclere initially employed five people and, since taking out a 0% interest loan from AAH-I in 2016, has hired an extra five.

“I am now servicing my second loan after paying back the first one,” she says. “This has helped me expand my business and satisfy my customers, making it easy to grow as the number of clients also continues to grow.”

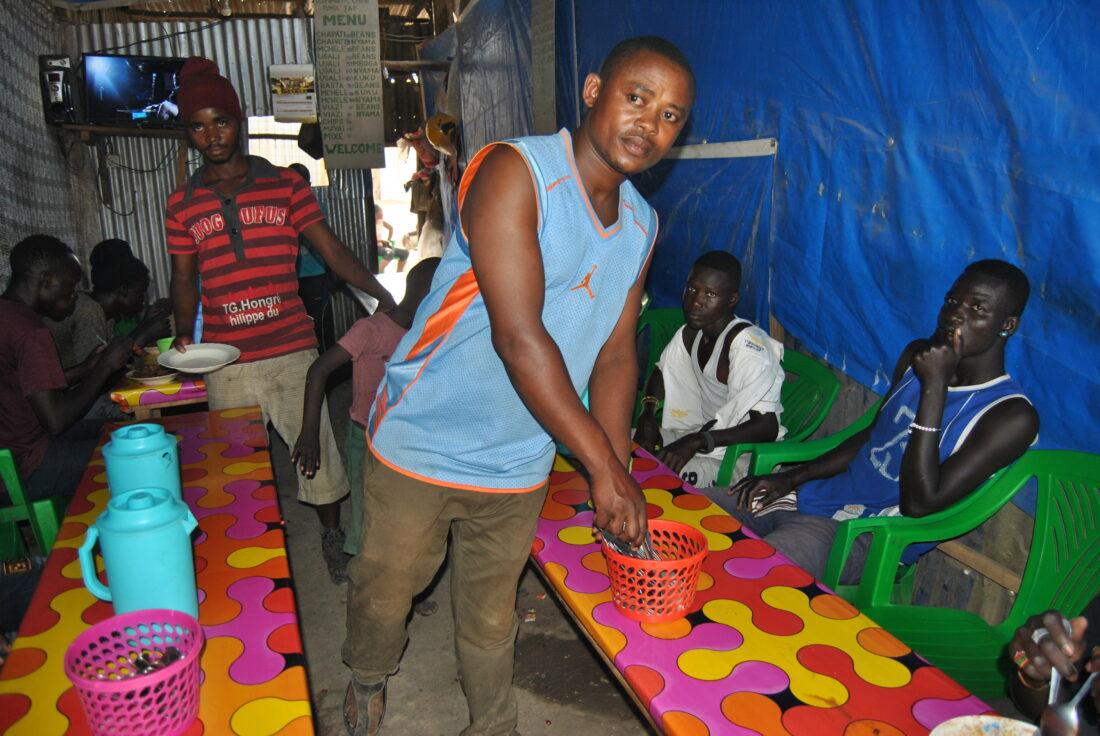

The hotelier and restaurateur

Gilbert at work in his hotel at Kakuma refugee camp.

Today, Gilbert Munyeneza oversees a bustling hotel and restaurant in Kakuma. On this late afternoon, young people and families eat their late lunches here as others dance and sing along to the Tanzanian music playing loudly. Business is good, but this has been a long time in the making.

Munyeneza left Rwanda during the war in the 1990s, seeking refuge first in Burundi and then Tanzania before reaching Kakuma in 2000. At that time, he was just 17 years old and despite promises by officials to resettle him and enrol him in school, none of that happened. He realised he would have to take matters into his own hands to survive.

“I was employed to ride a bicycle ferrying people between the camp and Kakuma town for Ksh5 ($0.05) per trip. Each day, I would pay the bicycle owner Ksh70 ($0.7), or Ksh350 ($3.5) per week. I didn’t have much of a choice and so I rode,” he says.

He saved what he could and, in 2003, pooled resources with a friend to buy their own bicycle for Ksh4,500 ($45). This allowed Munyeneza to make more income, which he used to start a shoe-selling business in 2006 and then to open his hotel and restaurant. This activity has grown impressively and now brings in enough money for him to hire six employees who earn between Ksh3000 ($30) and KSh6000 ($60) per month.

For the father of seven, now 36, this is still just the start.

“Even though this might be a local hotel, I have faith that through my hard work and prayer, I will expand it to something bigger and better,” he says. “This is just an infant stage, of a child crawling and almost getting up to walk.”

The basket weaver

Ndikuriyo weaving a basket at her house in Kalobeyei, Kakuma.

By the time Theodora Ndikuriyo arrived in Kakuma, the 65-year-old mother of eight had seen it all. She was first displaced from Burundi to Rwanda in 1993, but was then forced to move on further occasions to escape new traumas, losing her husband along the way. “Me and my children had to flee into Uganda and later Tanzania after which I came to Kakuma”, she says.

When she settled here, Ndikuriyo started weaving baskets. Back in Burundi, she had made her living making products and selling them in the capital Bujumburu, particularly around foreign embassies.

“This would put food on my family’s table and my children never lacked anything,” she says. “I decided to continue this here in the camp since it is a skill that I had learnt from my mother and one that I carry with me wherever I go.”

With some help from an international NGO, she started teaching other women of various different nationalities the skill. Now, a group of them weave baskets together that sell for about $3-5 each. Because they are unable to travel, another NGO, Action Africa Help-International (AAH-I), helps source the materials the weavers need and pays them for their labour. Another organisation, Bawa Hope, transports some of the women’s baskets to be sold at the UN shop in Nairobi and at UN events as well as in some duty free shops in airports.

The money Ndikuriyo gets for her making the baskets allows her to buy clothing and food, but she says she the activity would be much more profitable if she could get the materials and sell the products herself.

The young farmer

Ramadhan Hassan rides a water pump at Choro farm in Kakuma camp to water his farm.

Ramadhan Hassan, 23, and Ramadhan Tia, 22, are in form three at the Somali Bantu Secondary School in Kakuma. But when they aren’t busy studying, they can often be found tending to their vegetable plot at Choro farm, pumping water and sprinkling it across their leafy Jew’s mallow, known here as murere.

They are among the hundreds of refugees here who have decided to take up farming, digging shallow wells along the riverbeds for irrigation, to make some extra income.

“Even though we get food rations and some money from the UNHCR, it is not enough,” says Hassan. “We sometimes have other needs like books, clothing and many other things, and farming is our only way to get them.”

Some farmers operate under an initiative led by the Kakuma Refugee Assistance Programme (KRAP) whereby groups of ten people work together to plant a crop of their choice. AAH-I also offers support, delivering seeds to farmers and, with funding from UNHCR, has built some solar-powered boreholes and wells.

Through activities such as this, refugees produce a significant amount of food. This allows them to supplement the dry food portions they get from relief agencies with green vegetables and sometimes sell the surplus.

The business lender

Peter Manyang’ at his office at the Kakuma 2 settlement

At Kakuma 2, Peter Manyang’ is checking the accounts books in his tin-walled office. The 32-year-old teacher and university graduate from South Sudan is the secretary general of the Wunda Youth Group, which gives out loans to refugees in the camp.

The initiative is led by 22 people, all from South Sudan. The group received a $5,000 grant from the Tony Elumelu Foundation in 2019 and has a further $2,000 revolving loan from AAH-I.

“We finance 20 small businesses within the camp and also benefited from training on financial literacy, which now enables us to run our resources very well”, says Manyang’.

He explains that Wunda Youth Group plans to fund both new and existing small businesses in Kakuma, giving them the best chance for growth.