Debating Ideas is a new section that aims to reflect the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series, publishing engaged, often radical, scholarship, original and activist writing from within the African continent and beyond. It will offer debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments books.

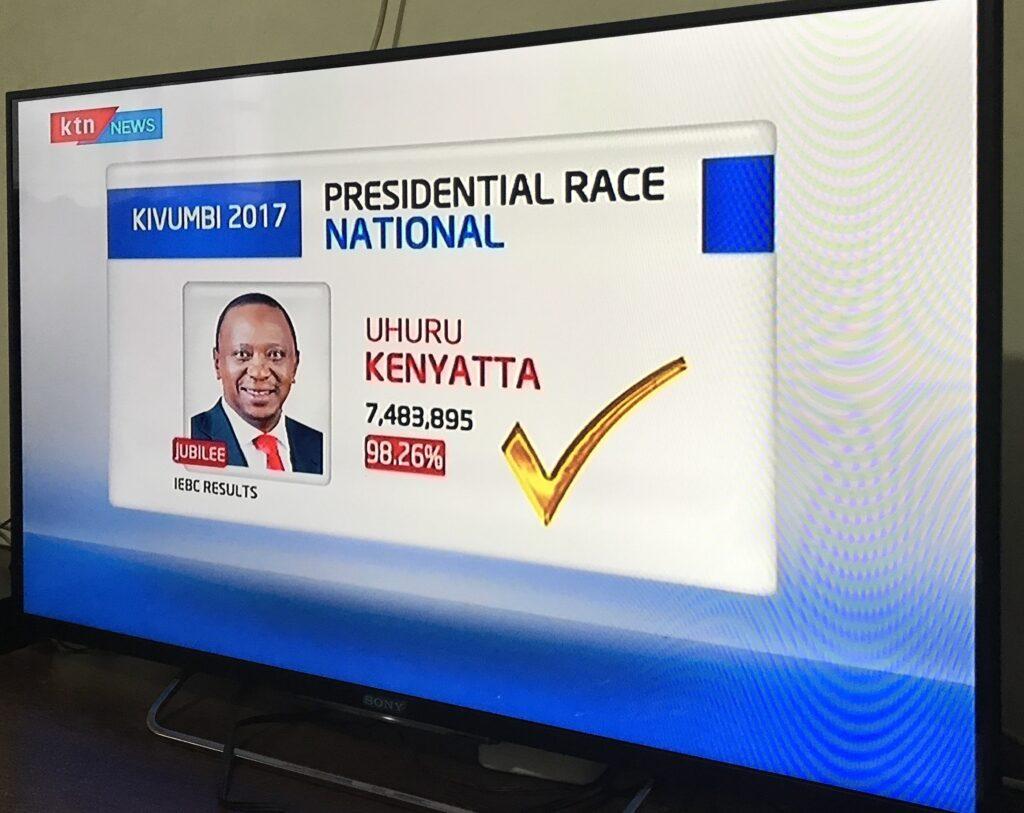

Kenya’s Election Results. Credit @Rachel Zimmerman

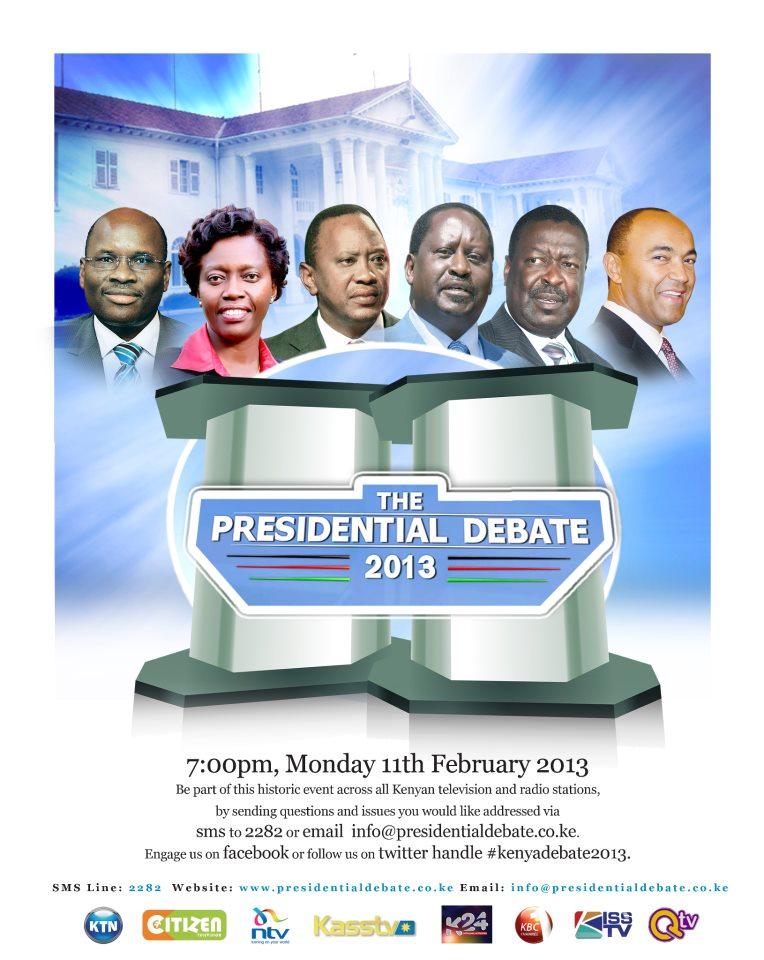

Cambridge Analytica’s electoral manipulation of the US’s 2016 election along with its abuse of Facebook data became an international scandal. Now in the midst of the 2020 presidential election, US social media platform companies are under increasing scrutiny for their response to misinformation and their responsibility to democracy. Yet, before Cambridge Analytica came to the US, it had been quietly field-testing its electoral strategies in Kenya as meticulously documented in Nanjala Nyabola’s recent book published in African Arguments, Digital Democracy, Analogue Politics: How the Internet Era is Transforming Kenya. Cambridge Analytica, a subsidiary of the UK based political consultancy Strategic Communication Laboratories (SCL), was incorporated in Delaware on December 31, 2013 – two months before Kenya’s 2013 general election. Cambridge Analytica first tested its tactics in Kenya in 2013 when the firm conducted its first of two 50,000-person surveys to identify Kenyan voters’ “real needs” and “fears” – jobs and ethnic violence. The firm subsequently enacted a branding campaign for the Jubilee Party targeted at youth voters, which ultimately helped cement the culture of impunity in Kenya’s fragile democracy with the election of Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto. The two forged an alliance to fight off their International Criminal Court indictments for crimes against humanity following the meticulously orchestrated 2007 electoral violence. The PR company BTP Advisers, along with Cambridge Analytica, successfully reframed the indictment as neocolonialism and an infringement on Kenya’s sovereignty, ensuring that there would be no criminal accountability. In this article I demonstrate how political consultancies, such as Cambridge Analytica, test their electioneering methods in developing countries with little regulatory oversight before taking their technology to the bigger electoral prizes.

On the world stage, Kenya is recognized for its growing digital economy, revolutionary use of mobile money, and geostrategic stability. Nairobi serves as a base for multinational corporations and international organizations on the continent, making Cambridge Analytica’s 2013 electoral success a marketing ploy on its now-defunct website. For Cambridge Analytica, Kenya was the ideal country to demonstrate viability in the open-source and unregulated sphere of corporate information operations since Kenyans are digitally connected and engaged. Furthermore, Kenya has a history of elite manipulation of ethnicity for electoral gains stemming from British colonial divide and rule tactics. Targeted traditional media campaigns have mobilized voters and incited violence in the past, making Kenya an “easy” client as well as a lucrative market for political consultancies due to the high price of politics in a winner-takes-all system.

Since Cambridge Analytica’s self-reported market differentiation was its social media operations, Kenya was an ideal testing ground due to the nation’s established internet and communication infrastructure. The push for digital connectivity began with Kenya’s state-backed mobile money service M-Pesa which launched in 2007 and was cemented in 2009 when Kenya became the first East African country to connect to international fiber optic. Kenya’s rapid digitization has created one of the most elaborate surveillance states in the developing world. In Uhuru Kenyatta’s first term he continued to advance government digitization. Kenyatta built off his predecessor’s Integrated Population Registration System (IPRS), which collected data from a dozen databases held by different government agencies – including birth, marriage, electoral, and hospital registers. In 2014, Kenyatta introduced the e-citizen platform, which enabled mobile payments for government services that ranged from passport applications to marriage certificates. Despite this massive state-led effort to aggregate citizen data, Kenya had not yet adopted data protection legislation regarding the collection, centralization, and sharing of its citizen’s data by both Kenyan state actors as well as domestic and international firms. This would prove to be of central concern in Kenya’s 2017 election.

In the intervening years of Kenyatta’s first term, Cambridge Analytica worked on the UK’s Brexit campaign and expanded its business across the pond to include mega donor Robert Mercer. Steve Bannon, the former executive chairman of Breitbart (another Mercer investment), was installed as a board member and vice-president of Cambridge Analytica in order to assist Cambridge Analytica’s parent company, SCL, to set up shop in the US. With Mercer’s monetary backing and political clout and Steve Bannon’s media know-how, Cambridge Analytica propelled Donald Trump to the presidency. In the US, Cambridge Analytica successfully amplified divisive rhetoric to mobilize Donald Trump’s base, divide his opposition, and sow doubt in the very institutions that provide a check on executive power. The firm claimed that their data enabled the micro-targeting required to win with a narrow margin of “40,000 votes” in three states propelling Trump to victory in the electoral college. Despite criticism of being all high-tech bluster, Cambridge Analytica and its parent company SCL had extensive experience creating information campaigns in over 200 elections worldwide. The weaponization of platforms in the 2016 US election demonstrated the power that well-placed propaganda can have in undermining democratic trust and, ultimately, democratic institutions in developed democracies.

Meanwhile, while Cambridge Analytica was busy cashing in on the British Leave campaign and Donald Trump’s presidential run, Uhuru Kenyatta was working to tighten his control over Kenya’s media houses. Since Kenyatta first took office in April 2013, Human Rights Watch has documented a state-orchestrated campaign against journalists. Despite free expression and media rights being enshrined in Kenya’s 2010 Constitution, the executive has sway over Kenya’s media since government advertising accounts for 60 to 70 percent of all advertising revenue. This has bred a culture of self-censorship around topics related to land, corruption, and security and has forced investigative journalists into the blogosphere. But, it has also undermined Kenyan’s trust in traditional media houses pushing many to seek their news through Facebook and WhatsApp groups, which are particularly vulnerable to misinformation campaigns. Thus, to assert control over the platform information space, President Kenyatta contracted Cambridge Analytica again for a reported USD 6 million – a small chunk of change in Kenyan politics where according to local media reports, just to become a county governor requires at least USD 6 million.

In the run-up to Kenya’s 2017 election, the promise of a “digital election” was hailed by the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) as the panacea for electoral fraud and manipulation. The French firm OT Safran Morpho was selected to provide the technology required to power Kenya’s Integrated Elections Management System (KIEMS) and provide the biometric capability to help the IEBC electronically authenticate every voter. The 2017 election between intergenerational rivals, Uhuru Kenyatta’s Jubilee Party and Raila Odinga’s opposition NASA party, became one of the world’s most expensive elections to date on a cost-per-voter basis. The IEBC spent USD 25 per voter on elaborate biometric and electronic measures in conjunction with printed ballots. In total, Kenya’s 2017 election cost upwards of USD 1 billion.

The 2017 election proved to be a historic one, not because of the sheer expense, but because it was the first time a Supreme Court nullified the election of an incumbent in Africa and only the fourth time globally. The Supreme Court cited irregularities and illegalities in the transmission of results as the reason for the annulment and ordered the IEBC to hold a fresh presidential election within sixty days. The IEBC’s over-focus on voter technology acquisition, and the international electoral observers’ narrow mandate to combat conspicuous fraud on election day, did not address the more insidious methods of election tampering, which included attacking the free press and fomenting ethnic strife through targeted social media campaigns.

Following Kenya’s Supreme Court’s landmark decision for fresh elections, political brinkmanship quickly ensued with President Kenyatta labeling the Court’s decision “a judicial coup” and opposition leader Raila Odinga declaring a boycott against the re-run. Ultimately, with the opposition boycotting the polls, Kenyatta was re-elected with 98 percent of the vote, although only 39 percent of Kenyans cast their ballots. In light of the 2017 decision of the Supreme Court to nullify the election, French-firm OT Safran Morpho was discovered to own Kenya’s electoral servers and, in effect, Kenya’s voter registry and biometric data. To contextualize, Europe’s landmark General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which codified data privacy and security rights to EU citizens, had launched the year before – highlighting a significant loophole that facilitated this transnational data grab. This GDPR loophole thus leaves the door open for European multinational corporations to continue to monetize data collected in developing countries until these nations establish their own data protection laws.

In Kenyatta’s second term, he has continued to consolidate the information sphere with the 2017 passage of the Computer and Cyber-crimes Bill, which covers a wide range of cyber crimes including false publications. If convicted, these crimes come with long prison terms and hefty fines. The crime of false publications comes with a fine of 5 million Kenyan shillings (USD 50,000) or two years in prison. This Cybercrimes Bill has raised concerns with Kenyan media professionals and the larger independent pundit blog-sphere that it could codify online government censorship. The Bill also enables the government to “access any information, code or technology which is capable of unscrambling encrypted data” and “require any person in possession of decryption information” to grant them access. Privacy International has provided substantial evidence that Safaricom, Kenya’s largest telecommunications provider, regularly provides government agencies access to customers’ data, although Safaricom’s CEO denies this accusation. Nevertheless, the government holds 35% of Safaricom, and under the 2017 Cybercrimes Bill, “bulk collection” – including metadata, SMS, and audio phone taps – is allowed. This is not the first time Kenya’s government has surveyed communications en masse. However, real-time collection is much more expansive than the firewall filtration system used to block SMS text messages to tamp down on ethnic hate speech following the 2007 and 2013 elections. There is due cause for concern that the same government that hired Cambridge Analytica to push its message on social media would be able to monitor private online spaces and, in effect, be the arbiter of truth.

Democracies are vulnerable to social media misinformation, whether that be Kenya, the UK, or the US. And as Nanjala Nyabola has pointed out, Nigeria, India and Brazil as well. Until Cambridge Analytica’s downfall, there had been no accountability nor public reckoning with firms micro-targeting and profiting from large-scale data aggregation of publicly available information. What is clear is that in upcoming elections, the methods of outside observation to guarantee free and fair elections need to change to incorporate the social media sphere. Platform companies – Facebook and Twitter – may have internal guidelines to discern and combat misinformation, but the scale of this dilemma will increasingly put developing democracies at higher risk. Domestic data protection and privacy laws will be critical to reining in multinational firms. Kenya’s 2019 Data Protection Act is a step in the right direction, but laws are only as strong as they are enforced.