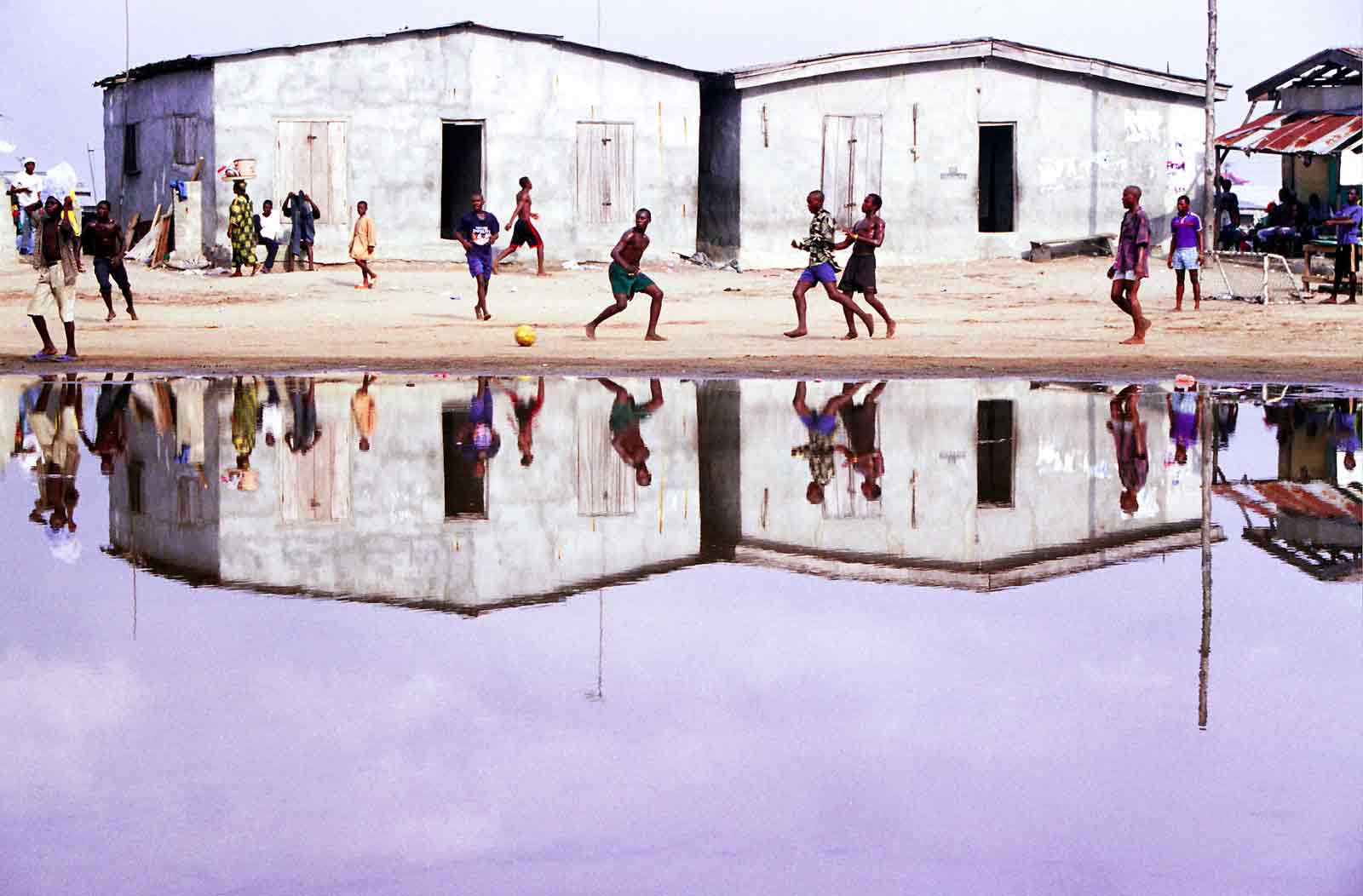

Photo essay: We are all goal diggers

Photojournalist Andrew Esiebo explores how young Africans appropriate non-conventional spaces to play football.

Teenage boys play beneath an ongoing railway construction in Marina, Lagos, Nigeria 2018

This article is part of “In the name of the beautiful game“, a series of articles on football and how it intersects with all aspects of our lives.

Beneath bridges under construction, on market streets choked with carts, merchants, and customers, in open palace courtyards, at dusk, on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean, victory comes by way of crumpled paper or tin cans bound together by tape, to make a big ball. Sometimes the ball is rubber. Other times the ball is borrowed from other sports. The goal posts could be stones set atop themselves. Or plastic bottles. There is hardly ever an actual net.

It is usually little children, teenagers, or young adults playing. They are following the tradition of a sport beloved across the continent. They are creating the subculture of street football. They move the makeshift ball in the air, guide it nimbly among themselves, across concrete, sand, thick vegetation, planks and other surfaces that otherwise don’t lend themselves to good football. They play in between open shop stalls carrying items that may break when met with the force of a kicked ball, or on a beach where wayward waves constantly threaten to take away the ball and perhaps even the players. They will play with anything and anywhere. No surface – ideal or otherwise – will get in the way of their game.

In a cleverly-titled exhibition, “Goal Diggers” at Nigerian gallery, Rele, and an ongoing body of work produced over the last 12 years, Nigerian photojournalist Andrew Esiebo captures the phenomenon of street football. In capturing these moments, Esiebo tests the limits of what’s known as the “beautiful game” Who really gets to enjoy soccer and where and how? Esiebo’s work indirectly comments on the problems of urban planning in the cities he shoots in, where the construction of yet another government office building might be favoured over recreational facilities. And if such facilities were to be built, they may be inaccessible, guarded and under lock and key. Who, then, has access to this beautiful game, a game so often said to be democratic, open to all across socio-economic realities?

Yet, away from politics, the glory of victory in street soccer is never forgotten. We asked a few football-mad players and fans across the continent to respond to Esiebo’s photographs. They were to recall their memories, dreams, ambitions as young footballers playing in the street, in non-traditional spaces that was available to them. We asked why and how they contended with the lack of otherwise ideal facilities to play the game they love. We ask what football meant to them, then. What their dreams were. Who they looked up to.

This is what they said:

The game continues at Marina Under Bridge, Nigeria 2018.

Mangi Mbileni, Content Producer & Entrepreneur, Johannesburg, South Africa:

“My fondest memory of playing football in the street was around 1994 in Orlando West in Soweto; we played an intense 5-a-side and on this particular day our star striker couldn’t play as his parents were away and he had to stay home to look after his younger siblings. I filled in for him, playing an attacking midfielder position. We played in the street using a tennis ball as a ‘soccer’ ball and used two little bricks as goal posts. I remember forcing my way through the opponents’ defence and scoring the winning goal just as the sun was setting! I always wanted to be a professional footballer. I was a pretty quick and skilled forward. I was convinced that I would one day play for Wits Football Club after completing school but my dreams were short lived because I went to boarding school in the Eastern Cape. If anyone knows anything about the EC you’ll know that football isn’t a terribly popular sport. Rugby is the main sport in winter and cricket in summer. My footballing heroes are Phil Masinga and Helman Mkalele.”

Dribbling in Tamale, Ghana 2007.

Kaggwa Myga Andrew, Writer, Kampala, Uganda:

“At Kisubi Boys, we played ‘one touch’ in the dormitory after the lights were switched off. Whenever the matron went to her cubicle, we would start playing quietly, then other people started carrying their balls into the dormitory. One day, the ball hit the matron as she had quietly stayed inside after switching the lights off. You could be shocked by what she saw when she switched the lights on, half the dormitory was in decker spaces playing ball.”

Children playing after school in Dakar, Senegal 2017

A game in bloom, in Kumasi, Ghana, 2007

Mike Tigere Mavura, Lecturer, Harare, Zimbabwe:

“My friend’s older brother was in high-school and he was so good he was recruited by a professional football team for one of their junior teams. He started to train about five of us in the very same methods that were being imparted in him with the professional junior team: how to play in space, one touch football, improving technique etc. That first session changed everything. Our team pretty much cleared every other team in sight from then on. The street mirrored people’s lives and experiences in the township: intimate, fun, hard, full of trickery, rebellious. Games were intense. We loved the competition whether for a 5-a-side match or actual 11 v. 11. Sometimes we would each put an equal amount of money for a winner-take-all match, we called it ‘money game’. Those were the best games. My heroes were the Nigerian Rashidi Yekini. Kalusha Bwalya was special too.”

On the edge of the Atlantic in Accra, Ghana 2017

On the edge of the Atlantic in Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2017

Yvon Edomou, Diplomat, Abidjan, Ivory Coast:

“My best memory of playing in the streets was when we did under the rain, those soft rains while the sun is still shining. We played in the streets because the field was occupied by elders. We would usually play in the parking lot next to the main pitch. I did not want to become a footballer but growing up I loved Ivory Coast’s Youssouf Fofana.”

Children playing in front of the Emir’s palace in Maiduguri, Northern Nigeria, 2006

Nlisana Anderson, Entrepreneur, Gaborone, Botswana:

“The streets were the best. I remember where I grew up we used basketball posts as our target, so for one to score they would have to shoot and hit the metal stand of the basketball posts anywhere and it would be a goal. That taught us a lot as you had to aim really good to score. The street had the best adrenaline rush and were more competitive in skill and winning. In my neighbourhood, football was very popular. I wanted to be a professional player but resources limited me, well at my time my favourite stars were Nwankwo Kanu, JJ Okocha of Nigeria, Michael Essien of Ghana.”

Game Day at the foot of 2nd longest bridge in Africa, Third Mainland Bridge, Nigeria 2018

Enos Nyamor, Culture Journalist, Nairobi, Kenya:

“Growing up and playing on the streets was so natural to us. Although Nairobi was still growing, and there were many undeveloped spaces, there was still no proper playgrounds. But what is most memorable is that, more than anything, we cared more about our flip flops. While they could be used as posts, any case of loss or tear could earn one severe punishment. And so it was interesting to watch us playing with the rubber flip flops strapped on our elbows. The streets were more accessible and also close to home. In case one was needed at home for some errand, they could easily be reached. Besides, Nairobi was not flooded with cars at the time, and we thought we could make use of the idle murram roads. The streets were a compromise. Every time I was in the field, I dreamed that I was in the process of becoming one of the greatest defenders Africa has ever produced. If even such concept exists at all. And as I grew up, I wanted to become a footballer who is also a doctor or an intellectual. A footballer educated to the tooth! We actually had a footballer from my mother’s side of the family. One of my second cousins, Zablon Amanaka. He played for the Kenyan national team.”

A walkway becomes a field in Jamestown, Ghana 2018

Bright Ackwerh, Visual Artist, Accra, Ghana:

“One of my best memories was being an unofficial ball boy for the school team of the Accra Academy where Asamoah Gyan, one of Ghana’s Black Stars was playing then as a student. I grew up on the Campus of Accra Academy so as family of staff members members we were permitted to use the school pitch. If we didn’t get access to it we would play on any other bare ground because all we needed were rocks to make our posts. I actually wanted to be a footballer. When I got admission to senior high school I had to make that choice between playing and going to school because I had just signed my first contract with a local team. I ended up choosing school.”

A few kilometres away from Apapa, Nigeria’s most important port town, a game of monkey post is in session, 2006

*All photos courtesy of Andrew Esiebo and Rele Gallery.

The unity of the continent is the right solution to face the challenges facing Africa to defend itself and protect its economy from the tumultuous forces that prey on the world and want it weak and fragmented.

methotrexate side effects usmle https://plaquenilx.com/# can hydroxychloroquine get you high

https://cialiswithdapoxetine.com/ cialis 20mg

chloroquine dosage hydroxychloroquin hcq medication