Manchester in ruins: The demise of northern Nigeria’s industrial hub

A failed industrial boom in Kaduna ran one community aground. Decades later, promises of industry have risen again, but the scars linger.

Textile Road, Makera, Kaduna, a relic of past industry.

Kaduna, the former capital of colonial Northern Nigeria, named for the rivers and crocodiles that once filled its territory, used to be home to an industrial revolution. It was famed for its transport facilities, an abundance of water from the river Kaduna and the presence of raw materials, especially cotton.

In 1955, the premier of Northern Nigeria, Sir Ahmadu Bello, harnessed these resources with a £1.25 million investment (pdf, about $40 million today). Subsequently, around 60 industrial firms – including textile mills, breweries, petrochemical and automobile factories – came to operate in Kaduna, serving its immediate community and the entire country. These companies collectively became the second largest employer after the government with a 500,000-strong workforce. Once rural villages like Kakuri, located in the industrial area of Kaduna, were transformed and uplifted.

Soon, Kaduna earned the alias “Manchester of West Africa”. However, the revolution did not live long.

In fact, it witnessed a stunning reversal. In the 1990s, Nigeria’s military regime of the time was pushed into implementing a structural adjustment programme formulated by the International Monetary Fund. This deregulated Nigeria’s currency and led to the privatisation of public-owned industries, which increased the costs of importing materials. At the same time, local oil refineries deteriorated and electricity supply became erratic. The cost of doing business shot up. Factories closed. In Kakuri community, hundreds of thousands of workers lost their jobs without severance payments or entitlements.

Nortex, one of the foremost textile companies at the height of Kaduna’s industrial revolution.

An abandoned steel company

Fast forward almost three decades later, Kakuri is now a small city flanked by massive walls, the edges of derelict companies’ compounds. But a new industrial boom is happening.

Going through Kakuri, you will see a new $200 million investment Mahindra tractor assembly plant with the capacity to put together 3,000 tractors per year. Across the street is Blue Camel energy, a renewable energy production plant and training academy. On the Kaduna-Abuja expressway, there is an Olam poultry and feed mill, a $150 million investment.

But Kakuri and its people are far from what and where they used to be. Many still live in the shadows of the failed revolution that came before. Unlike in the heydays of the previous boom, the new industrial buzz is attracting skilled workers from outside the community. Kakuri’s residents, many of whom are unskilled in modern technology, will likely only be spectators.

We visited Kakuri and spoke to these survivors about the pain they inherited from the previous downfall and whether this new industrial wave will heal their scars.

We met Raymond Abah at the gate of Arewa Textiles, amid overgrown weeds and derelict structures. He is the site’s chief security officer, working with a handful of police officers to prevent the pilfering of equipment.

“I have been working here since 1992. When I started, the Japanese were in charge. Since the foreigners left, nothing is working. The government has been making false promises. We are angry. I am angry. Many people have died without their benefits. Some have run away from their families because of shame. We are tired of the promises of new industries. Life is difficult.”

Raymond Abah

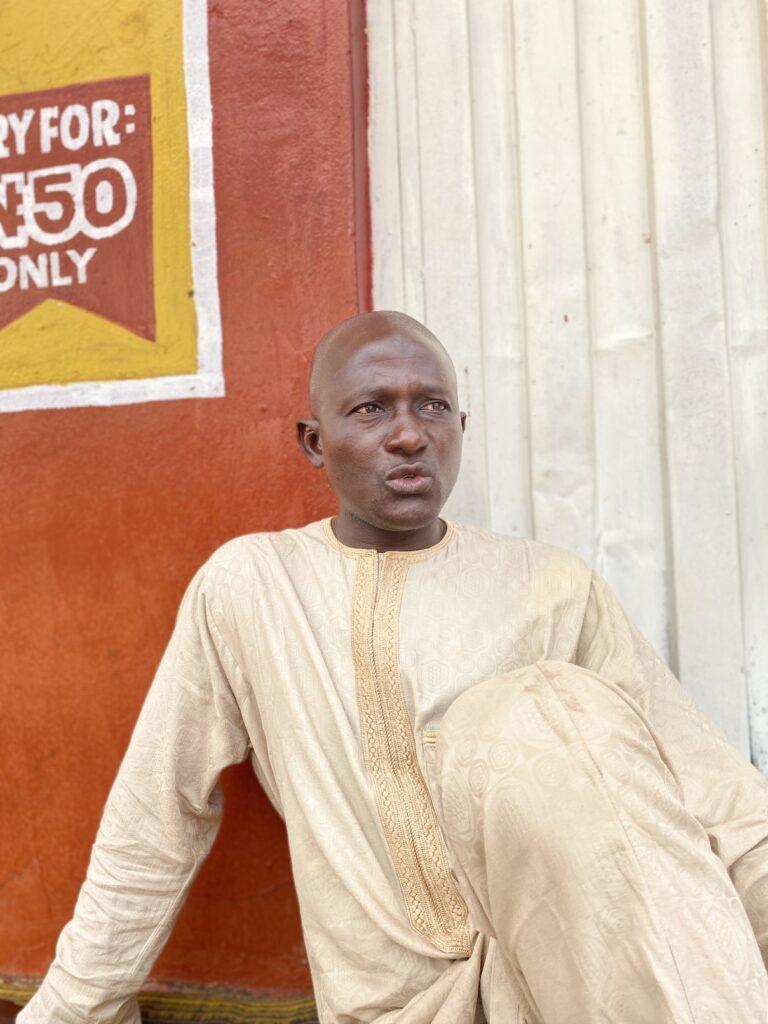

Abdullahi Sani is the leader of Makera Youth Association in Kakuri. We met him at the animal market where he was selling rams in preparation for the Eid Festival.

“I have heard of the new solar panel company, but it is not my concern. It is not helping me like the textile industries used to. What I am concerned about is the textile industries. The current government bragged a lot about reviving the textile mills in Kakuri before the election, but there is nothing to show for it. I was born and bred here in Kakuri and I grew up knowing the textile mills as the economic hub of this area. I used to buy textile materials from the mills and take them into town to sell. If these industries were working, my business of meat selling will have boosted too. I could have been supplying the canteens with meat. They do not have any canteen for my meat in the solar panel company. Everything is on standstill.”

Abdullahi Sani

Maryam Abdulkarim, a trader, has a ramshackle zinc and wooden kiosk just outside Nortex Nigeria Limited, selling bread, biscuits sachet water and soft drinks.

“I opened my shop 20 years ago and it was filled with provisions, but since the mills closed, my shop became empty. I used to make up to two thousand Naira in a day but now all I manage to sell is sachet water and if I am lucky, I make fifty Naira in a day.”

Maryam Abdulkareem

Abdulkareem’s shop.

Isiyaku Adamu Baba is a former worker at Supertex Limited.

“I worked for five years at Supertex and I was a union member. The closure of these mills has been a catastrophe. Our children and brothers are vandalising and stealing equipment from these industries to sell. There are no jobs, the children here could not afford a sound education, and now they cannot even benefit from or work in the new industries coming up. Our children do not have a future. All we can do now is pray. And for us the reality is, it is impossible to revive these textile mills.”

Isiyaku Adamu Baba

Arewa Textiles Mill

Ahmad Rufai works in the Environmental Health Department of the Kaduna State Local Government.

“I once applied for a job at the textiles but unfortunately I wasn’t successful. I am sad with the closure of the textiles. I know people that died of heart attacks due to the closure. Some hanged themselves to death, some resorted to petty crimes and theft, while others had to leave Kaduna completely because of frustration. Even with the coming of these new industries, we have not seen any big economic change. One thing that was constant when the textile mills were functioning was cash flow and life was easy. I agree there are new industries now, but where is the money? Life is just more difficult.”

Ahmad Rufai

A security officer at Nortex Nigeria Limited premises.

Kamaruddeen Jimoh is a carpenter.

“I am commonly known as Jasper from my footballing days with Arewa Textile Football Club. I was paid 10 Naira then. But things broke down with the sacking of workers and this place became an abandoned area. I am really hoping our children can benefit from the new industries, but I am also afraid. Everything is now computerised. It is not like the former textile mills that needed 3,000 workers to operate. Now a single machine can do the job and maybe only 200 workers needed to support it. I am still optimistic though, at least the new industries will finally return this area into the economic hub it used to be.”

Kamaruddeen Jimoh

Hajiya Albarka is a food vendor.

“Before, my restaurant was inside the Arewa Textile canteen. People will eat and pay after receiving salary. With the closing of the textile, some people died without paying me, some people are still alive, but when you see them, you pity them, so I can’t ask for anything from their hand. I hope the new industries can work, so people can enjoy again so that our children and grandchildren can find work and maybe even us, we will enjoy life once more.”

Hajiya Albarka

Kabir Abdulrahman is a student.

“I was born and brought up in Kakuri. I am glad I am still in school right now, but I live with unemployed and uneducated youth stealing equipment from the abandoned industries. If the working condition of the textile industries were still good, I will have loved to work there after graduating. I am hoping the new industries will reduce the level of unemployment. Many people here have no jobs, and no education. Only a few of us get to graduate from secondary school. It is sad because a lot of my friends whose parents worked in textile cannot even find work in the new industries because they have no education as there was nobody to take care of them after their fathers died or disappeared.”

Kabir Abdulrahman

Text: Sada Malaumfashi. Photos: Salmah Ja’eh.