Kony’s rebels remain a threat, but they’re also selling honey to get by

The LRA has gone from a fearsome fighting force to a small band struggling to survive. Is now the moment to finally end the group?

A park ranger finds a mosquito net from an LRA campsite in 2013. Credit: Jonathan Hutson/Enough Project.

Joseph Kony has long been one of Africa’s most notorious warlords. Through the 1990s and 2000s, his rebel group, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), struck terror across northern Uganda and the surrounding region. His fighters abducted tens of thousands of children and adults and killing large numbers of people in the conflict with the Ugandan government. For decades, former fighters spoke of Kony’s iron grip and harsh punishments of those who dissented or tried to escape.

Today, however, a different story is emerging. Testimony from more recently defected combatants suggests Kony has lost command over many of his officers. Moreover, they say the infamous leader no longer sees the LRA as a movement battling to overthrow the Ugandan government but as a band of “refugees” fighting for its own survival.

Over the last few years, Kony has been living in Kafia Kingi, a contested enclave on the borders of Sudan, South Sudan and the Central African Republic (CAR). According to recent defectors, the LRA is now made up of just several dozen people, including Kony’s sons Salim and Ali. They say the group’s main activities consist of subsistence farming and sometimes selling honey at local markets.

Kony himself is said to be healthy but is now almost 60-years-old. Other LRA commanders, with little or no direction from their leader, continue to roam remote regions of eastern CAR and northern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where they loot and abduct from small farming communities in order to survive.

How did this happen? What is still left of the rebel movement? And what can be done to finally resolve one of the region’s longest-running sources of insecurity?

The slow unravelling of the LRA

The LRA came to notoriety in the 1990s through its large-scale abductions and violence targeting civilians in its conflict with the Ugandan government. In the late-2000s, after two decades of fighting, the rebel group shifted its operations to the borderlands of the DRC, Sudan, South Sudan and the CAR. Its last acts of major violence were in 2008 and 2009 when it committed large-scale massacres against the Congolese population.

By 2011, the rebel movement was much weaker and Kony’s sub-group had established itself in Kafia Kingi. Here, it avoided attacking civilians and, for several years, continued to receive some basic supplies from the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), which had given it substantial support in the 1990s and early-2000s.

In early 2017, Uganda and the US stopped its military operations against the LRA. There were fears that this would allow Kony to rebuild the combatant force, which had reduced in size by at least 75% since 2008 in part due low morale and waves of defections. Kony did indeed give orders in early 2018 to forcibly recruit new members, leading to the abduction of more than 40 children and youth in the following months.

Importantly, however, our evidence suggests that Kony’s efforts to rebuild the group then stopped. It seems the rebel leader gave up trying to maintain command and control of the LRA outside of his own faction. Commanders of sub-groups in CAR and DRC, who had once brought ivory and supplies to Kony’s Kafia Kingi hideout, began operating more in their own interest. Even the Sudanese Armed Forces, long-time enablers of Kony’s operations, stopped supporting him.

It was in this context that a recent defector explained how Kony declared in his last “discussion” with fighters in June 2018 that the LRA was no longer fighting the Ugandan government and that its members were now “refugees” who had to find their own way to survive.

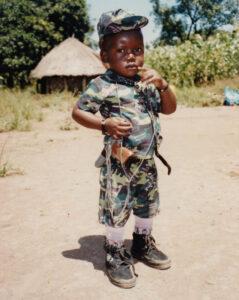

Ali Kony, as a toddler, in 2003. (c) Kristof Titeca, ARLPI.

From intimidation to survival

The above trajectory helps explain the fundamental change in the nature of the LRA’s violence over the last decade. As data from the Crisis Tracker project shows, the LRA killed 17 civilians in 2018-19, a 99% drop from its last period of peak violence in 2008-09 when it killed 1,975 civilians. This is not only because of fewer attacks, which reduced by just 54%. Rather, it suggests a change in strategy. The LRA today appears far less interested in violent intimidation and more inclined towards acts of survival such as looting basic food supplies.

Testimony from defected rebels reinforce this data, highlighting how individual LRA commanders have given orders to stop killings. These evolving tactics are likely a response to the group’s increasingly fragile position. The LRA is a declining fighting force, Sudanese support has stopped, and morale is eroding. The new priority is simply to survive.

Given this context, it is not a surprise that there are fragmented, but consistent, reports of LRA tactics evolving even further to include trading peacefully with local populations. In conversations with civilians in one region of eastern CAR, rebel commanders have reportedly emphasised their will to “live together in peace”. The data on LRA violence also seem to confirm this tendency: in the last six months, there only was one LRA attack in this region of CAR.

What does this mean for the future of the LRA?

All of this does not mean the LRA is finished. In 2019, the rebels still abducted 222 people, including dozens of children. But these new developments do suggest that there is an opportunity to further reduce the LRA’s violence. If the group’s main “glue” is disappearing – Kony’s command over the movement – this presents an important moment to rejuvenate defection messaging targeting the group.

As the recent interview with a defector shows, Kony may not want to surrender, but others do – perhaps even his sons, Salim and Ali. Many are discouraged to do this, however, because – according to the defector – they no longer know where their homes are or where they would go. Others fear retaliation by the local population, regional governments or militaries.

Historically, defection messaging played an important role in addressing the LRA threat. For example, Mega FM broadcasts in northern Uganda were often listened to by rebel fighters and the testimonies of former combatants encouraged hundreds to defect. Similar initiatives, often costing little money and implemented by local civil society leaders, also showed success in CAR and DRC in subsequent years. However, funding for these campaigns has dried up since mid-2017, leading to a predictable outcome: fewer combatants have defected, instead choosing to survive by looting local populations.

Our interviews and recent testimony from defectors confirm both the usefulness and urgency of renewing defection messaging. While undermining the LRA from within is not a silver bullet for a region threatened by a complex array of conflicts, it could finally remove one long-standing threat from the lives of tens of thousands of civilians.

this is informative thanks so much.

Thank you for the post on your blog. Do you provide an RSS feed?