They were sentenced to death. Got law degrees in prison. Then got free.

In Kenya, where millions struggle to get access to justice, some inmates are studying the law so they can help themselves and each other.

Willis Ochieng’ graduating from his law degree at Kamiti maximum security prison in October 2019. Credit: African Prisons Project

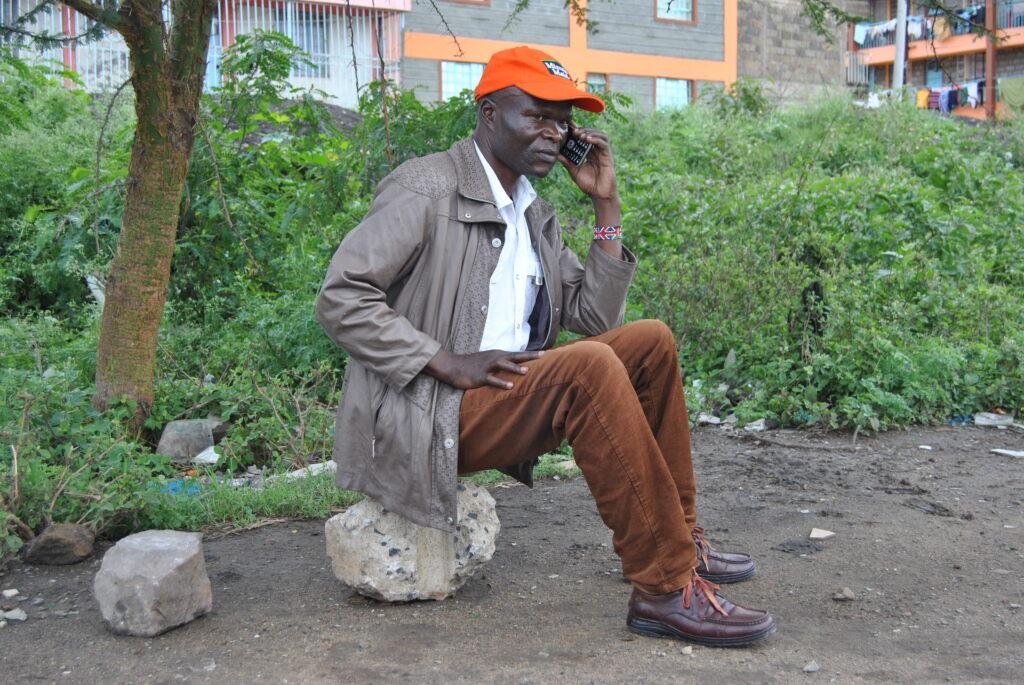

On a bright Saturday morning, Willis Ochieng’ watches on as some children play football on a muddy field on the outskirts of the capital Nairobi. A bit further away, some women are sorting rubbish into piles alongside locals washing cars in the sun.

For most, this may be a very ordinary scene, but for Ochieng’ it is one to savour. Until a few months ago, he thought he would spend the rest of his life in jail. He had already been in prison for almost two decades.

“Things have changed,” he exclaims as he pulls out his phone from his pocket. “On my arrest in 2001, I left a mobile phone with an aerial!”

Ochieng’, who admits to selling drugs in high school and being a member of a gang called Baghdad, had been tried and convicted for robbery with violence. In Kenya, this crime is punishable by death, though in reality this equates to life imprisonment; no one has been executed by the state since 1987.

With most of his life still ahead of him, the young man who’d had little education was thrown into Kodiaga prison in Kisumu County where he believed he would see out the rest of his days. Little did he know that nearly twenty years later, he would walk out of a prison a free man, having successfully argued in court for his own release.

Willis Ochieng’ outside prison after twenty years. Credit: Dominic Kirui.

When he first reached prison, Ochieng’ was keen to keep studying and took to it well. After a while, he sat his secondary school exams before going on to teach his fellow inmates at various different jails to which he was relocated over the years. Eventually, he found himself at Kamiti prison where he taught other prisoners chemistry and biology.

That’s where he was in the late-2000s when a new initiative called the African Prisons Project (APP) began. Founded by Alexander McLean, who trained as a barrister in the UK, the initiative began as a way to help provide access to justice for inmates in Kenya and Uganda.

“I met prisoners, usually young men like me,” he told African Arguments of his motivations for establishing the APP. “They had been in prison for years without a trial.”

For Ochieng’, the APP meant an opportunity to enrol in a course – conducted in partnership with the University of London – to study law. He grabbed it with both hands, going on to attain a law diploma and then a law degree along with 17 fellow inmates.

It was through this process that Ochieng’ and others learnt that they could apply for resentencing if they felt their punishments were not justified. Some APP paralegals helped them draft their applications and trained them in how to represent themselves in court.

Ochieng’ made his case in front of the judges and was ultimately successful, in part thanks to the argument that death sentences are no longer legal since Kenya’s passed a new constitution in 2010. He walked free soon after.

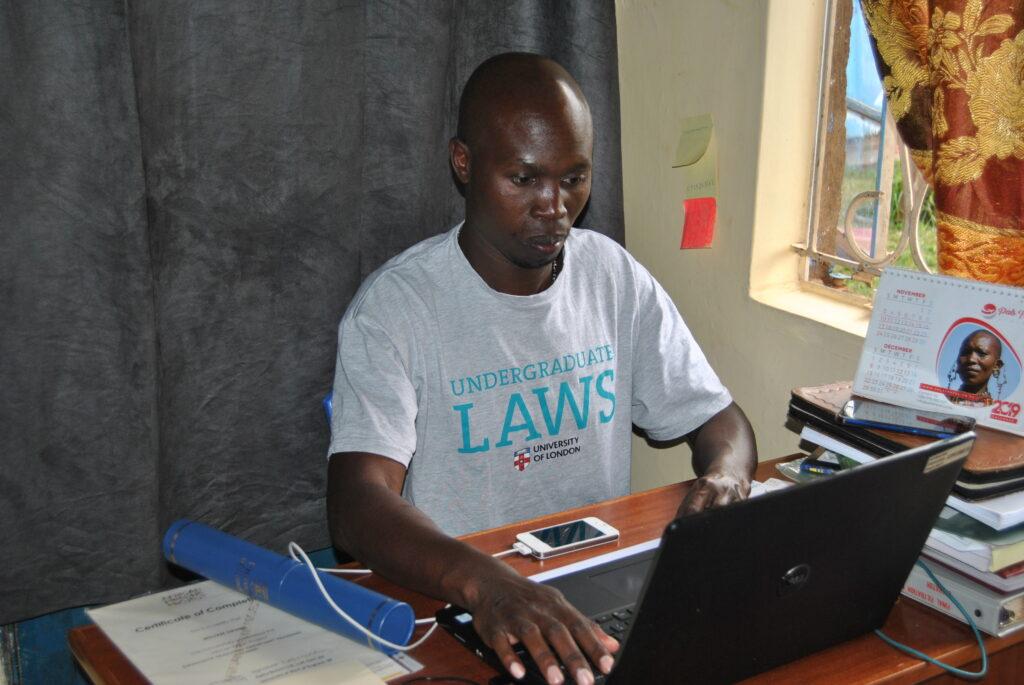

William Okumu working on his computer at his house. Credit: Dominic Kirui.

Ochieng’ now works for the APP as an interim researcher. His colleagues include other former inmates such as William Okumu, an administrator for the initiative’s legal education programme. Okumu also managed to reduce his sentence after learning law in prison.

“Studying [for a law degree] while in prison was a lot more fun and easy since everyone you met was a file,” he says.

Yet other former inmates help the programme run clinics – or “mini law firms” – in prison where law students and paralegals can offer legal aid. Overall, the APP currently works in 30 prisons and has 115 paralegals, 17 law graduates and 15 law students.

According to Mary Khaemba, Director for Rehabilitation and Welfare in Kenya’s prisons, these initiatives have made a huge difference to many prisoners, especially those who would ordinarily struggle to access the kind of legal support they need.

“[The students and graduates] have been very useful in writing appeals for their fellow inmates and actually that was our desire from the beginning since some of the inmates are very poor. Getting lawyers or advocates to write appeals for them or to defend them is a nightmare”, she says.

In Kenya, access to justice is a major problem. The country struggles to ensure all citizens get sufficient legal support and are treated equally by an overstretched legal system. It is estimated that of the over two million Kenyans arrested each year, less than a third even get charged in court.

Programmes like the APP can only make a small dent in this shortcoming, but for those who have had the opportunity to get legal advice or studied for law degrees while in prison, the effects can be huge. And the initiative is now looking to assist graduates do their bar exams so that they can run law firms of their own. For some like Ochieng’ and Okumu, what looked like the end of their lives turned out to be a chance for a fresh start.

“I regret that I went to prison because I disappointed so many people…somehow, I wasted ten years and seven months,” says Okumu. “But on the other side, I never regret it because it gave me an opportunity to think myself in a deep way. Inasmuch as I spent that number of years in prison, I made the best use out of it…It was a blessing in disguise.”